The physics of the universe appear to be fine-tuned for life. Why?

It appears that we live on the knife-edge, where only the narrowest combination of values for the fundamental constants allow life, and especially conscious life, to arise.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The fundamental constants of nature seem perfectly tuned to allow life to exist. If they were even a little bit different, we simply wouldn't be here. Given this grave existential fact, we are forced to ask a question: Why?

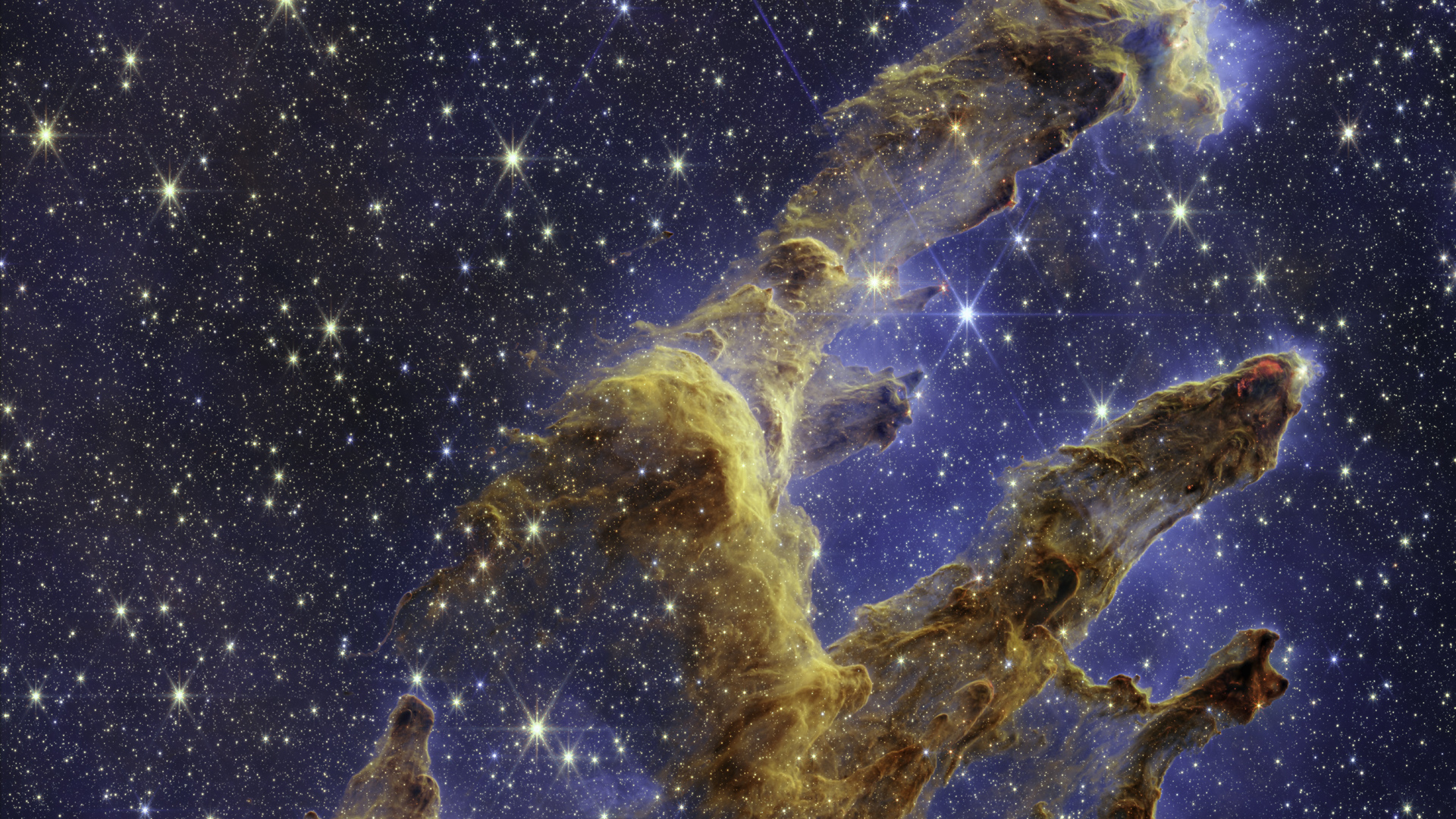

Our laws of physics contain several parameters with values that we cannot predict from theory alone. These are known as the fundamental constants. We can only go out and measure their values and then insert those values into our equations to make physics work. All told, there are about two dozen such numbers. They express such basic facts as the speed of light, the strength of the four fundamental forces, and the masses of elementary particles.

What's especially unnerving about these numbers is how carefully crafted they appear to be. If any were different, even by a tiny amount, our universe would be radically altered. For example, stronger gravity would make stars burn out faster, preventing the rise of solar systems and life-bearing planets like Earth. If the speed of light were faster or the electron were heavier, stars wouldn't even form in the first place. If Planck's constant were different, the cosmos would be totally unrecognizable.

It appears that we live on the knife-edge, where only the narrowest combination of values for the fundamental constants allow life, and especially conscious life, to arise.

This is the heart of the fine-tuning argument: that the universe appears to favor the existence of life. So why are we here?

One answer is to simply end the line of thinking right there. The constants are the way they are because if they were different, we wouldn't be here to observe it. This is called the anthropic argument: Life exists because otherwise, it would be impossible for life to exist.

Many physicists and philosophers consider this argument a little less than satisfying. While it does answer the question, we seem to have this nagging feeling that there's more to the story.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Another possibility is that there's more than one universe — that we live in a multiverse, with each different universe "sampling" different values of the constants. There are a few extremely hypothetical ideas in physics that can lead to the multiverse. One is through the concept of eternal inflation, where the very early universe never ended its period of rapid expansion and different portions of the overall multiverse "pinched off" to create their own bubble universes.

Another path to the multiverse comes from string theory, where extra spatial dimensions can twist up on themselves in a dizzying number of ways. Each possible arrangement would lead to new values of the physical constants, and even entirely new laws of physics. The range of possible combinations is known as the landscape, with our universe consisting of one point in that landscape.

In these multiverse-inspired ideas, there are a multitude of universes "out there" that don't support life — but this one does, so here we are. At the end of the day, it's still the anthropic argument, but at least it's one that explains how different values of the constants can be realized.

But there are issues with both of these ideas. Importantly, both are hypothetical and not supported by any available evidence. We don't know how regular inflation works and whether eternal inflation is even possible. Additionally, string theorists can't make the connection between a particular arrangement of the extra dimensions and the physics it generates, meaning we can't even make testable predictions.

What's more, eternal inflation and string theory contain their own constants that are not "explored" by different iterations of the multiverse. For example, string theory assumes a certain number of extra dimensions — a number that is not predicted by the theory itself. And eternal inflation requires any number of extra, unknown parameters to make it work.

So no matter what, we can't yet escape some form of fundamental constant, or some form of knowledge about the universe that we can't explain from our theories themselves. I suppose we'll just have to keep digging.

Paul M. Sutter is a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University, host of Ask a Spaceman, and author of How to Die in Space.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.