63 years after Sputnik, satellites are now woven into the fabric of daily life

World Space Week 2020 celebrates the impact of satellites on humanity.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

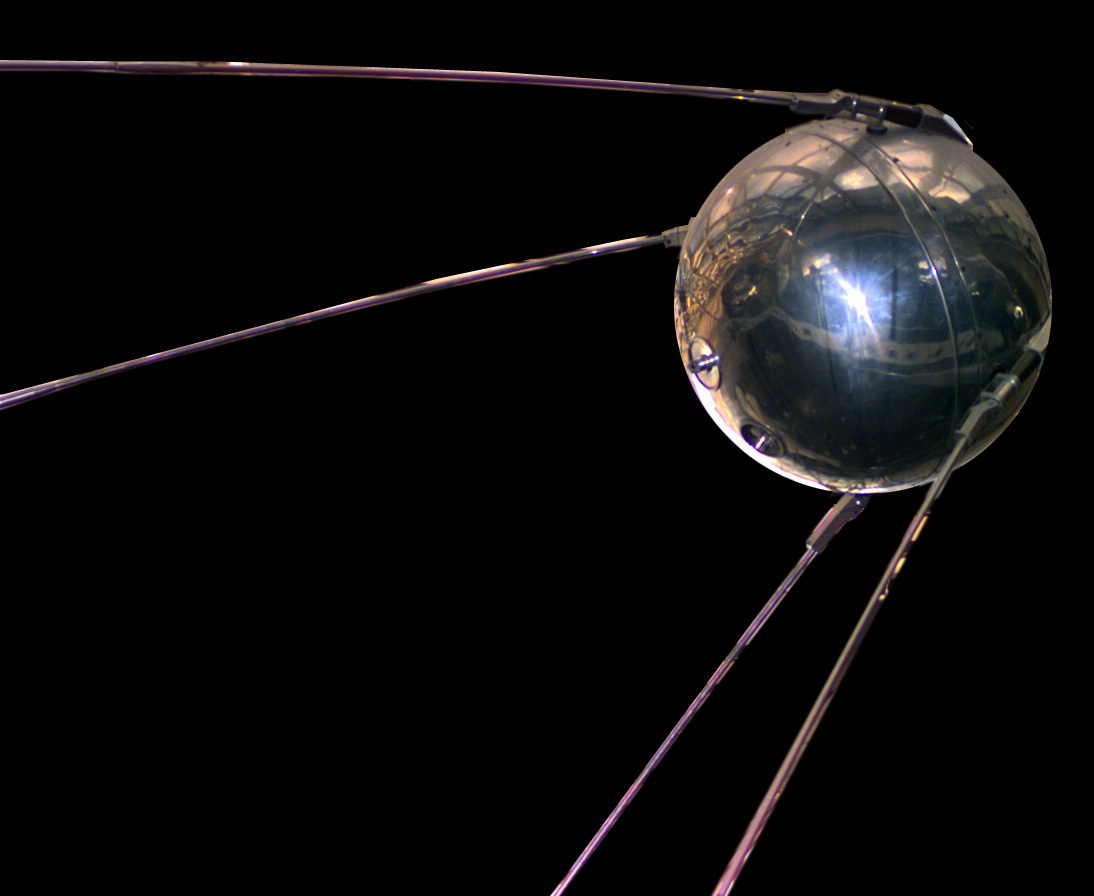

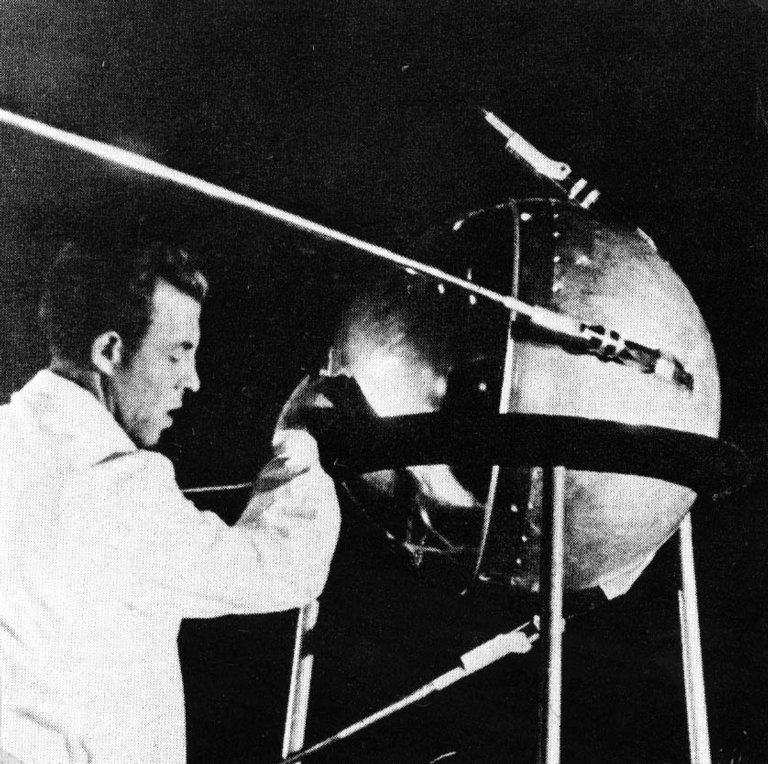

The pioneering flight of Sputnik, the world's first artificial satellite, 63 years ago this week had a deep resonance on Americans on the other side of the world from where the Soviet satellite launched.

Bonnie Dunbar, a five-time NASA space shuttle astronaut, grew up in rural Washington state in a set of "sheep herder cookhouses", she recalled in a NASA oral interview. There was no indoor plumbing at her place, and only a small oil stove allowed the family to stay warm.

"[There was] nothing around us," she said in the 1998 interview, recalling her first view of the satellite on Oct. 4, 1957. "At night, no lights to the north ... the Milky Way was a big white band across the sky. That's how I saw Sputnik. That was my first real introduction to spaceflight, was watching it go over.

Sputnik's flight was the opening shot in a lengthy space race between the United States and the Soviet Union to prove supremacy in the "high ground" of space. But as the race faded into history, Sputnik took on a larger role as the herald of a new revolution in observation and telecommunications.

The role of satellites and their impact on humanity takes center stage this week as part of World Space Week 2020, a celebration of space exploration and technology. This year's theme, "How Satellites Improve Life," explores how we rely on satellite technology every day.

Related: World Space Week 2020: Join the UN satellite celebration

More: World Space Week 2020 events and webcasts

Find out how Sputnik 1 kicked off the Space Age we enjoy today in our reference look here.

Thousands of satellites launched after Sputnik, in the following decades. At first these machines were tentative efforts to test television communications, Earth observation and at times, spying. Today, however, satellites are an integral part of Earth's infrastructure. We depend on satellites for everyday functions like using cell phones, browsing the Internet and checking the weather. And a new revolution with satellite constellations promises to have swarms of satellites delivering services to even the most remote areas of Earth.

"As someone who remembers when the first satellites were launched, I've observed how our relationship to these artificial orbiters has evolved over the past six-plus decades," emeritus cinema professor Jan Millsapps from San Francisco State University, who will be moderating a panel on satellites for World Space Week 2020 virtually on Tuesday (Oct. 5), told Space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Millsapps' favorite satellite as a child was Echo I, a metallized balloon launched on Aug. 12, 1960 that reflected microwave signals. She wrote to NASA asking for more information, and the info packet the agency sent back included a sheet of the shiny Mylar similar to what was used on the spacecraft. Millsapps retains the Mylar to this day, and added that the agency's information helped her earn an "A" on her middle-school science report.

Related: Sputnik 1! 7 Fun Facts About Humanity's First Satellite

"Early on, satellites had names – now there are too many to name," Millsapps added. "We learned, and sometimes worried, about each satellite as it launched. Sputnik was surprising and scary – even if it didn't have a bomb on board, the potential of sudden annihilation was right overhead. Telstar spawned a catchy tune we all could hum along to. Now there are too many [satellites] to name, too many to fret about, too many to study individually."

World Space Week's theme this year is satellites, in both the technological and cultural sense. Numerous presenters will elaborate on the theme. For example: Adrienne Provenzano, a volunteer informal educator who is part of NASA's Solar System Ambassador program, was so inspired by satellite technology that she composed seven original music pieces called the International Space Station Suite. (Excerpts are available here.)

Access issues and space junk

What exactly is a satellite? We explain here.

Satellites have also contributed to our culture due to their ability to link people across the world, noted World Space Week presenter Alice Gorman, a space archaeologist based at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia. But there are aspects of space that must be considered to improve access across the world.

She told Space.com that satellite technology access is a contributing factor to the division between rich and poor nations. Countries with low gross domestic product (GDP), she said, "are in this position because of systematic and historic inequities relating to colonialism and capitalism. Wealthy 'space-faring' nations shouldn't be too quick to congratulate themselves on being benefactors. Additional Earth observation data isn't going to fix global inequalities, without radical political change too."

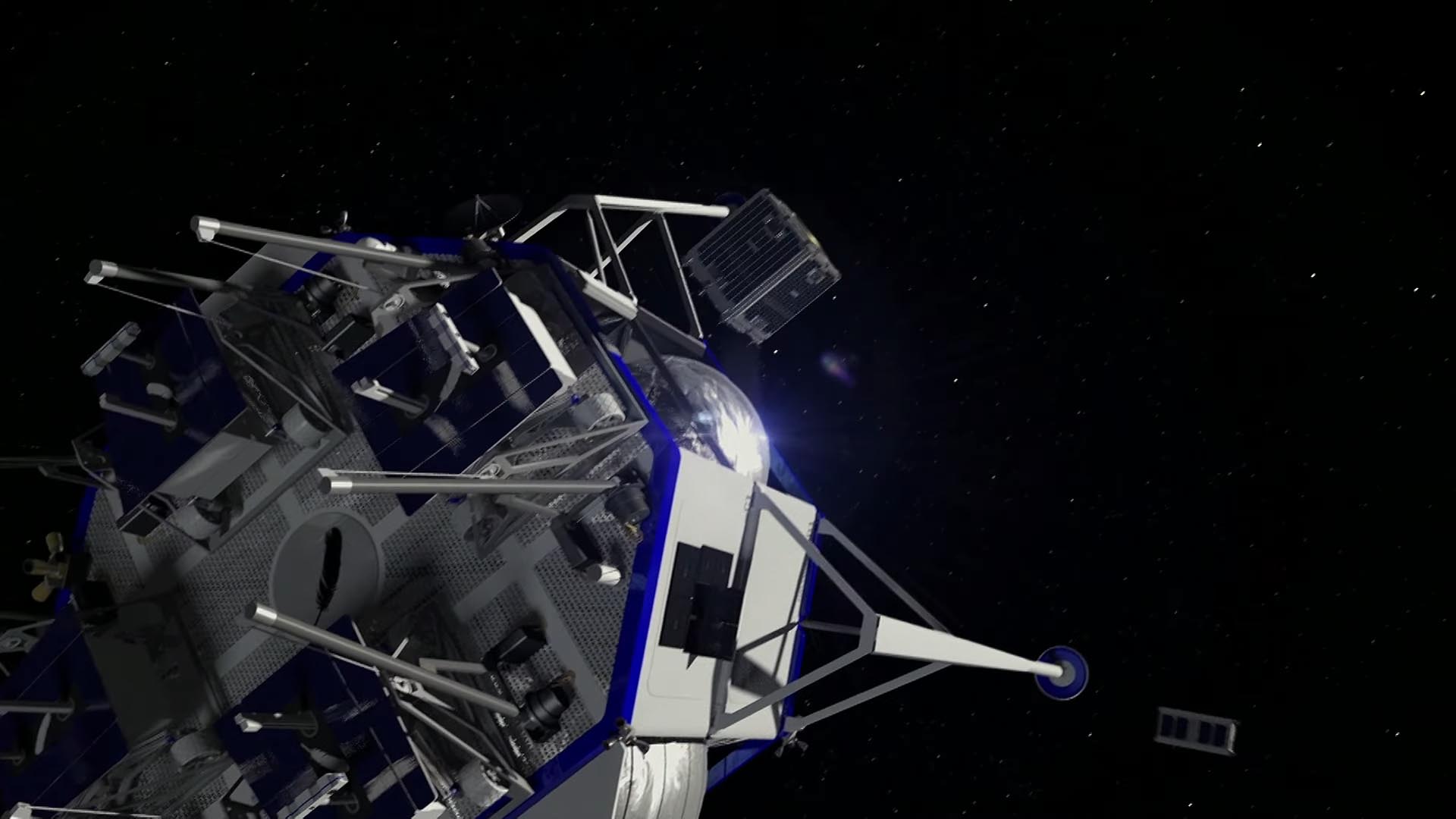

While broadband satellite constellations could bring more information to disadvantaged countries, that also comes with a price. SpaceX and OneWeb each hope to build satellite empires with tens of thousands of individual machines in space, but there are worries that such constellations could increase space junk. (The companies say they are being careful to follow protocols for minimizing orbital debris.)

Another concern is what it could mean if thousands of satellites continually criss-cross the sky, making it difficult for professional astronomers, amateur enthusiasts and indigenous peoples alike to observe the sky for scientific and cultural purposes.

"Higher numbers [of satellites] mean a higher probability that a satellite is in any particular direction we look toward the night sky, and a higher probability that they will affect astronomical data," John Barentine, director of public policy at the International Dark-Sky Association, told Space.com. "So far astronomers have mainly relied on dodging satellites in making their observations, but such high numbers of them will make that increasingly difficult."

In June, he noted, the U.S. National Science Foundation convened a panel of experts to understand how large satellite constellations could affect both professional astronomers and those who experience the night sky for other purposes. The final report contained recommendations such as limiting satellite brightness, avoiding putting satellites in orbits above 375 miles (600 km) and having a network of observers on the ground to monitor how much satellites interfere with sky observations.

In early October, scientists will create another report based on discussions from a dark-sky workshop hosted virtually by the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands. The new report will be presented to the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, Barentine said.

"Operators are gradually coming to the table," Barentine added. "SpaceX has been there since last year. OneWeb and Amazon are now participating. SpaceX has already demonstrated some design and operation changes to the Starlink objects that reduce their brightness, and engineering work is ongoing."

A growing community

The increasing numbers of satellites and applications in orbit really accelerated in the early 2000s with the development of the "CubeSat" format, which allows a standardized box to launch to orbit at lower cost, with smaller electronics. CubeSats first flew into orbit in 2003 and are slowly spreading across the solar system, to destinations such as Mars. These smaller, cheaper satellites have gradually led companies across the world to invest in building satellites or creating rockets to launch these satellites, creating a new space industry powered by private investors.

The novel coronavirus pandemic has led to even more demand for broadband Internet access as more of us attempt to access services from home, Brad Grady, principal analyst for mobility at consulting firm Northern Sky Research (NSR), told Space.com. (This is not a perfect solution, however, for remote areas that have few options to get online.)

"As a global society, I think we are only starting to appreciate and understand the importance of space-based infrastructure to our daily lives," he said. "From Earth observation images tracking wildfires in California, to emerging players such as SpaceX's Starlink providing connectivity to Washington State's wildfire response, to broadcasting TV signals across a country or continent, there are literally millions of services running over thousands of satellites at any given time."

Looking forward, NSR predicts that data-focused services will be on the rise. For example, a new mobile protocol called 5G promises to deliver faster mobile services that could better enable applications such as the Internet of things, which connects devices ranging from refrigerators to shipping containers. Connectivity will also be important for other types of satellite services, he said.

"We see more data-focused services to become the 'growth drivers' of the industry," Grady said. "These applications range from connecting households and businesses, to connecting passengers onboard airplanes traveling at 36,000 feet [11,000 meters] back to family on the ground, to building our understanding of the world around us through new Earth-focused space-based sensor platforms."

Maxime Puteaux from Euroconsult, another global consulting firm, finds that satellites are "instrumental" to the economy through various applications you may not think of. Examples include ATMs that connect to your bank information remotely, or trains or buses that use GPS to inform passengers of platform arrival times. Puteaux added that his firm also saw data as the future for satellite applications.

"The coming years will be all about more data, more frequently anywhere, anytime," he told Space.com. "Incumbent applications are evolving. Broadcasting has been the bread and butter of the commercial industry, but it is slowly declining because of on-demand video streaming services. Satellite operators are diversifying to broadband to meet these needs. Weather is evolving towards more accurate forecast models."

It is also possible that 5G and broadband satellites could finally open up Internet access in more isolated areas of the world, such as parts of rural Africa. Basuti Bolo is a space scientist who grew up in Botswana, and is now chair of educational technologies at Africa University in Zimbabwe. She will also be a presenter at WSW.

"I want to see Africa and other developing countries using space applications to manage the resources for sustainable development," she told Space.com, which could include applications such as finding areas of drought and potential areas of agricultural production, she added.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.