NASA's DART impact changed asteroid's orbit forever in planetary defense test

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A dramatic asteroid crash that slammed a NASA probe into a space rock in a first-of-its-kind test to defend our planet was more effective than scientists dreamed possible.

The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft slammed into a small asteroid called Dimorphos on Sept. 26. The mission was meant to test a potential planetary defense technique in case a large space rock ever threatens to collide with Earth, although NASA knows of no such threats in the foreseeable future. DART's goal was to shorten Dimorphos' orbit around a larger asteroid by at least 73 seconds, although scientists hoped the effect would be more like 10 minutes.

But the first calculations are in, and DART blew those milestones away, shortening Dimorphos' nearly 12-hour orbit by a whopping 32 minutes, NASA officials announced during a news conference on Monday (Oct. 11).

"Let's all just kind of take a moment to soak this in," Lori Glaze, head of NASA's planetary science division, said during the news conference. "For the first time ever, humanity has changed the orbit of a planetary body, of a planetary object. First time ever."

Related: 8 ways to stop an asteroid: Nuclear weapons, paint and Bruce Willis

The DART spacecraft, which cost about $314 million and weighed about 800 pounds (360 kilograms), launched in November 2021 and was equipped with a single instrument — a camera called Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical Navigation (DRACO). Then, the spacecraft trekked out to Dimorphos, which scientists had estimated was about 525 feet (160 meters) wide and which orbited a larger asteroid called Didymos once every 11 hours and 55 minutes.

DART made its dramatic arrival on Sept. 26, speeding in at 14,760 mph (23,760 kph) and sending back to Earth one image every second until crashing into Dimorphos in a distant collision 7 million miles (11 million kilometers) from Earth. That alone was the mission's first success, but the evening also brought early signs that the mission would smash through its expectations on all fronts.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As DART beamed photos back to Earth in the final few minutes, scientists got their first good look at Dimorphos, since from Earth, the moonlet and the larger Didymos appear as a single dot in a field of stars. Those images showed first an egg-like agglomeration of rocks, then finally a field of boulders, gravel and dust.

Congratulations to the team at @NASA for successfully altering the orbit of an asteroid. The #DARTMission marks the first-time humans have changed the motion of a celestial body in space, demonstrating technology that could one day be used to protect Earth. https://t.co/2X7Wcw3xYdOctober 11, 2022

That alone was enough for Tom Statler, program scientist for DART, to be confident the mission had moved Dimorphos more than its goal.

"When I saw Dimorphos come into view and when I saw there was not a single crater on it and there were a lot of what appeared to be loose rocks — and this was a totally non-scientific, by-eye measurement — I looked at it and I said, 'This is not going to be 73 seconds.' And it wasn't,'' he said during the news conference.

Although scientists are still analyzing the results, the orbital change, which represents a 4% difference from Dimorphos' previous orbit, may have been strengthened by the amount of debris that the impact sent shooting into space, Nancy Chabot, coordination lead for DART at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, said during the news conference.

The aftermath

The mission's main finding so far is the change in Dimorphos' orbit, but speakers at the press conference also unveiled new images of the impact's aftermath.

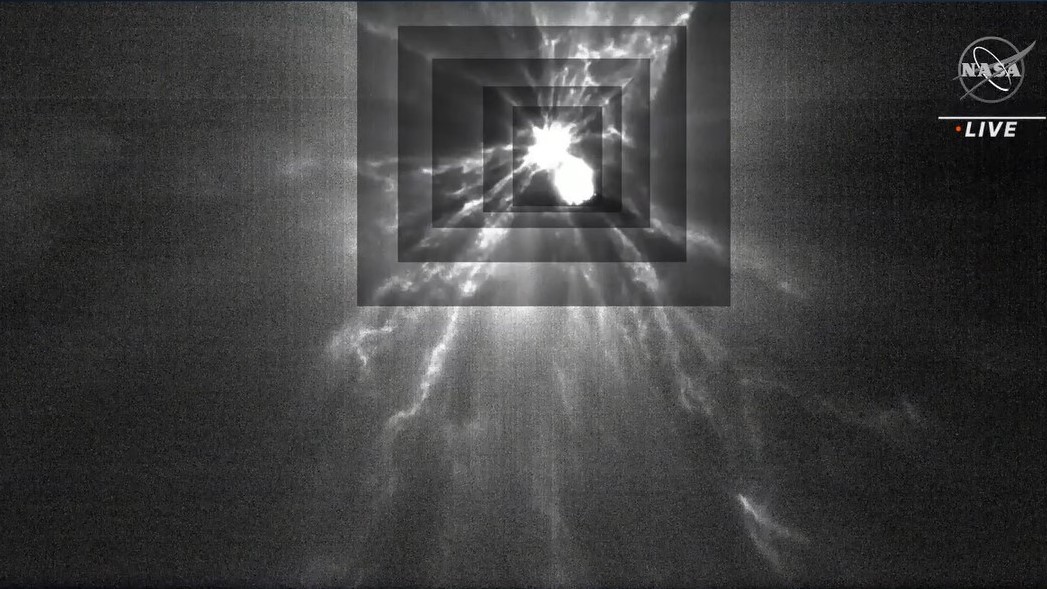

Statler unveiled a new image from LICIACube, the small Italian cubesat that hitched a ride to Didymos with DART then photographed the impact site about three minutes after the collision. The new image was processed to increase contrast and better show the details of the debris — and the details abound.

"Every little wiggle in those streamers, every little blob, every little particle that you see, is a clue to something," he said. "It's a clue to something that happens on the surface of an asteroid when an object impacts it."

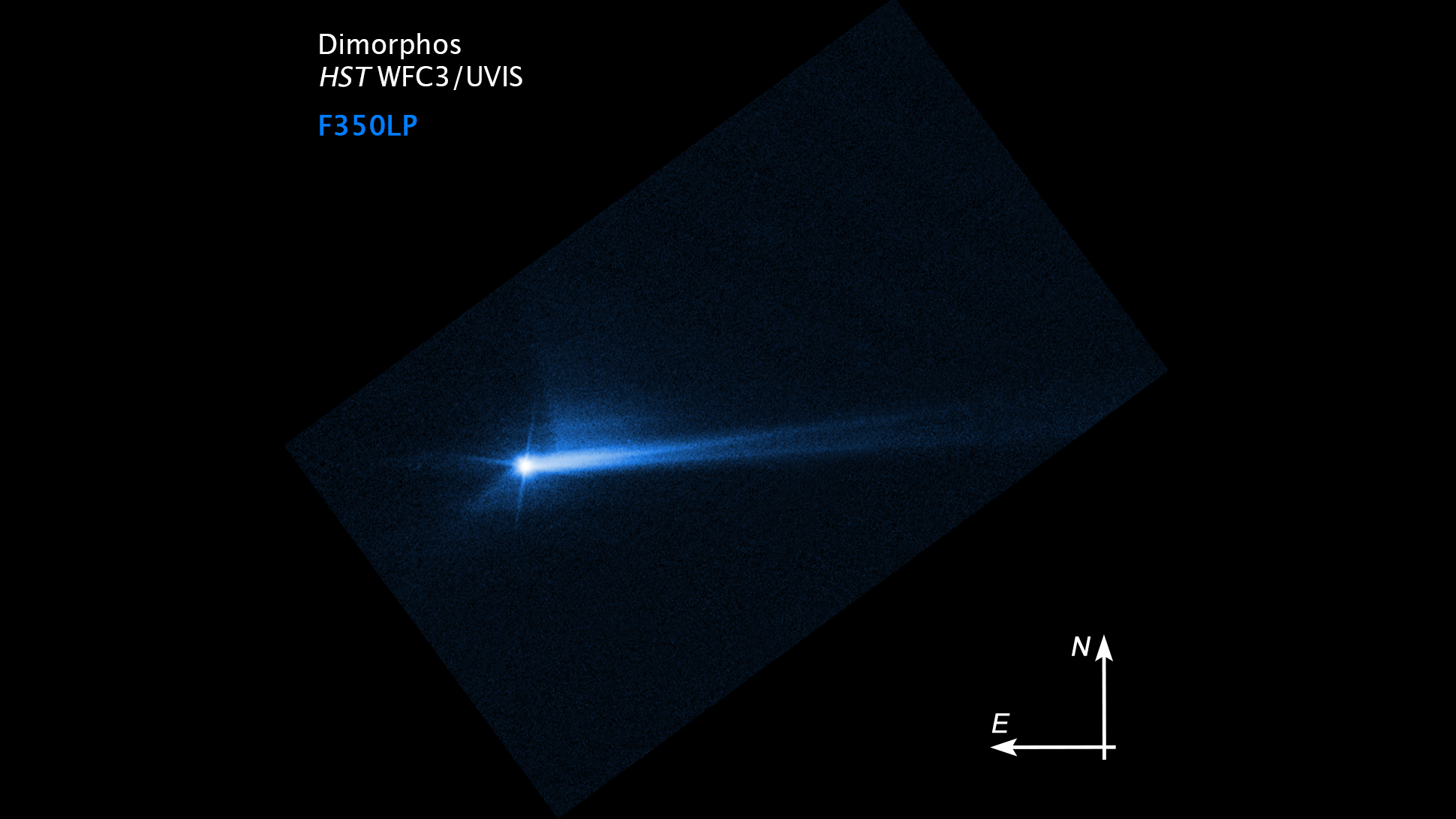

NASA also shared an image of Dimorphos taken by the Hubble Space Telescope on Saturday (Oct. 8). The photo shows a wide cone of debris that the sun has slightly collapsed on one side since earlier images of the collision's aftermath.

The Hubble view also shows the long tail of debris, which stretches 6,000 miles (10,000 kilometers) into space. Since previous photographs, the new image shows that the tail has split into two; Glaze said scientists were still working to discover what caused the fork.

"The tail is spectacular — this amount of ejecta that you're seeing. And it's continually evolving," Chabot said.

Telescopes on the ground and in space will continue to watch the debris from DART's impact on Dimorphos over time, she noted. In addition, the DART team is still gathering additional data on the moonlet's orbit.

The 32-minute change announced today comes with an uncertainty window of two minutes on either side that scientists hope to narrow even more. Scientists are looking for any potential wobble in the orbit created by the impact, Statler noted.

Observations for the mission will continue into next year, Chabot noted. The European Space Agency will also launch a follow-up spacecraft, called Hera, in 2024 that will explore Didymos and Dimorphos in much more detail than DART could on its fleeting visit.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.