8 ways to stop an asteroid: Nuclear weapons, paint and Bruce Willis

We currently know of no asteroid hazards for Earth, but planetary defense experts are on the case in case of a threat.

We live in a solar system filled with debris. Some of it may be hazardous.

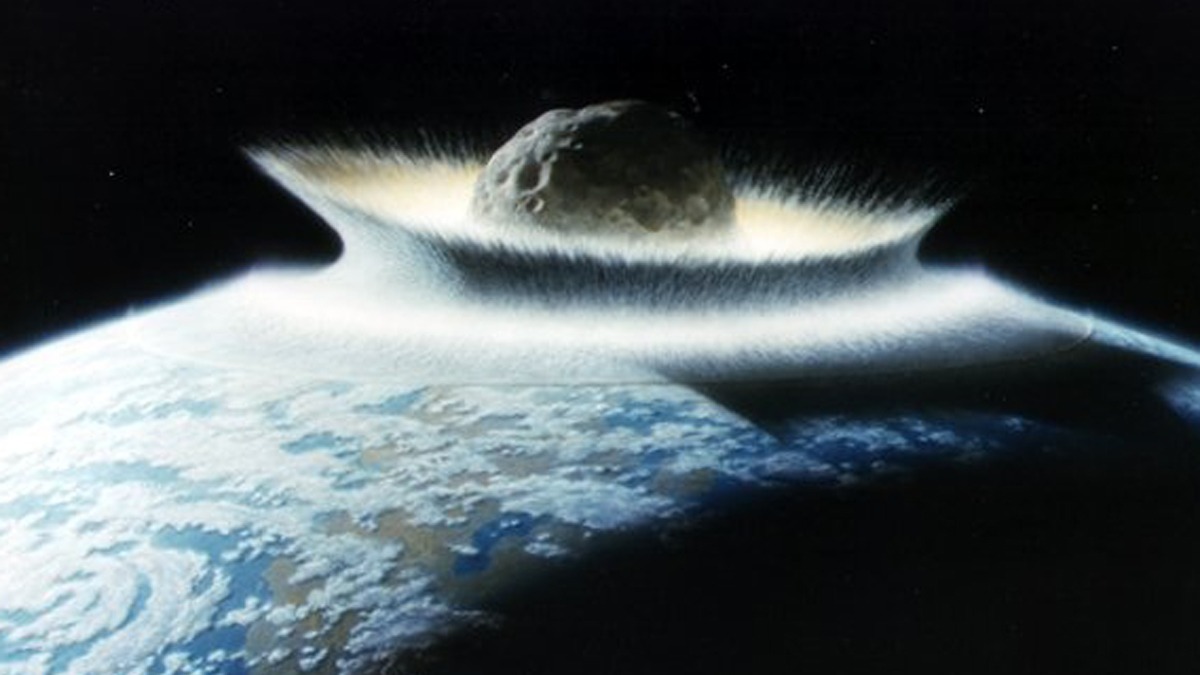

Once in a very great while, an asteroid or comet may come zipping into Earth. That happened to the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, altering our planet's evolution forever. Smaller bolides have come crashing in during more recent history, including an explosion in 2013 over Chelyabinsk, Russia.

Here are eight ways that planetary defense specialists (and Bruce Willis) suggest we can keep our planet safe from space rock threats.

Related: If an asteroid really threatened the Earth, what would a planetary defense mission look like?

No threats yet, but we have a plan

NASA personnel and countless telescopes around the world keep a sharp eye on the skies in case of threatening asteroids and comets. They scan the night sky regularly and then plot the orbits of any newly discovered small worlds. Decades of searching have found nothing to worry about yet, but scientists want to be prepared nonetheless.

The agency's Planetary Defense Coordination Office and planetary defense experts have come up with several scenarios to stop our planet from receiving incoming space rocks. The work is early-stage, but already we're testing some ideas on Earth and in space.

Related: Scientists spot 10,000th medium near-Earth asteroid in planetary defense milestone

Kinetic impactor

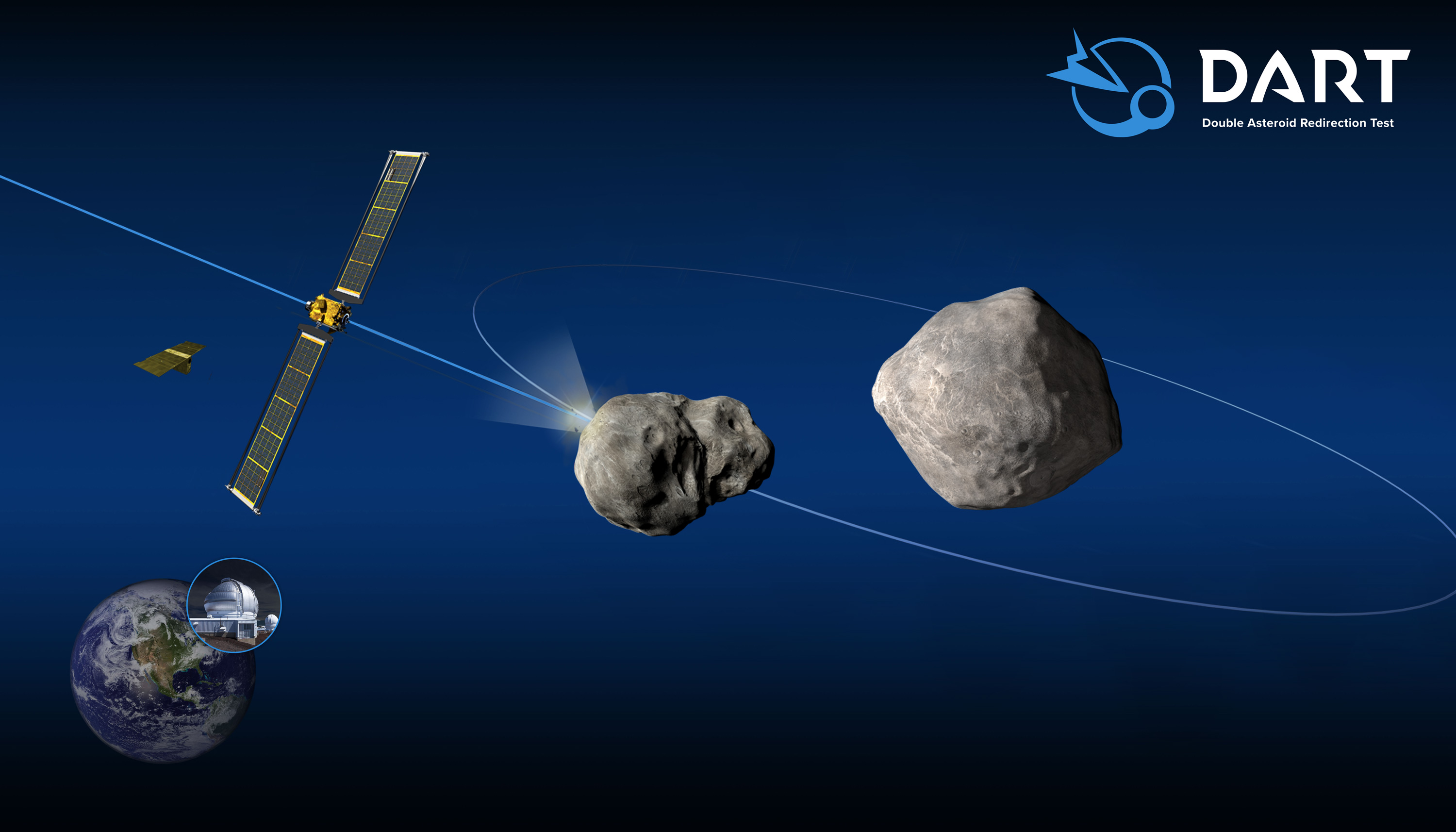

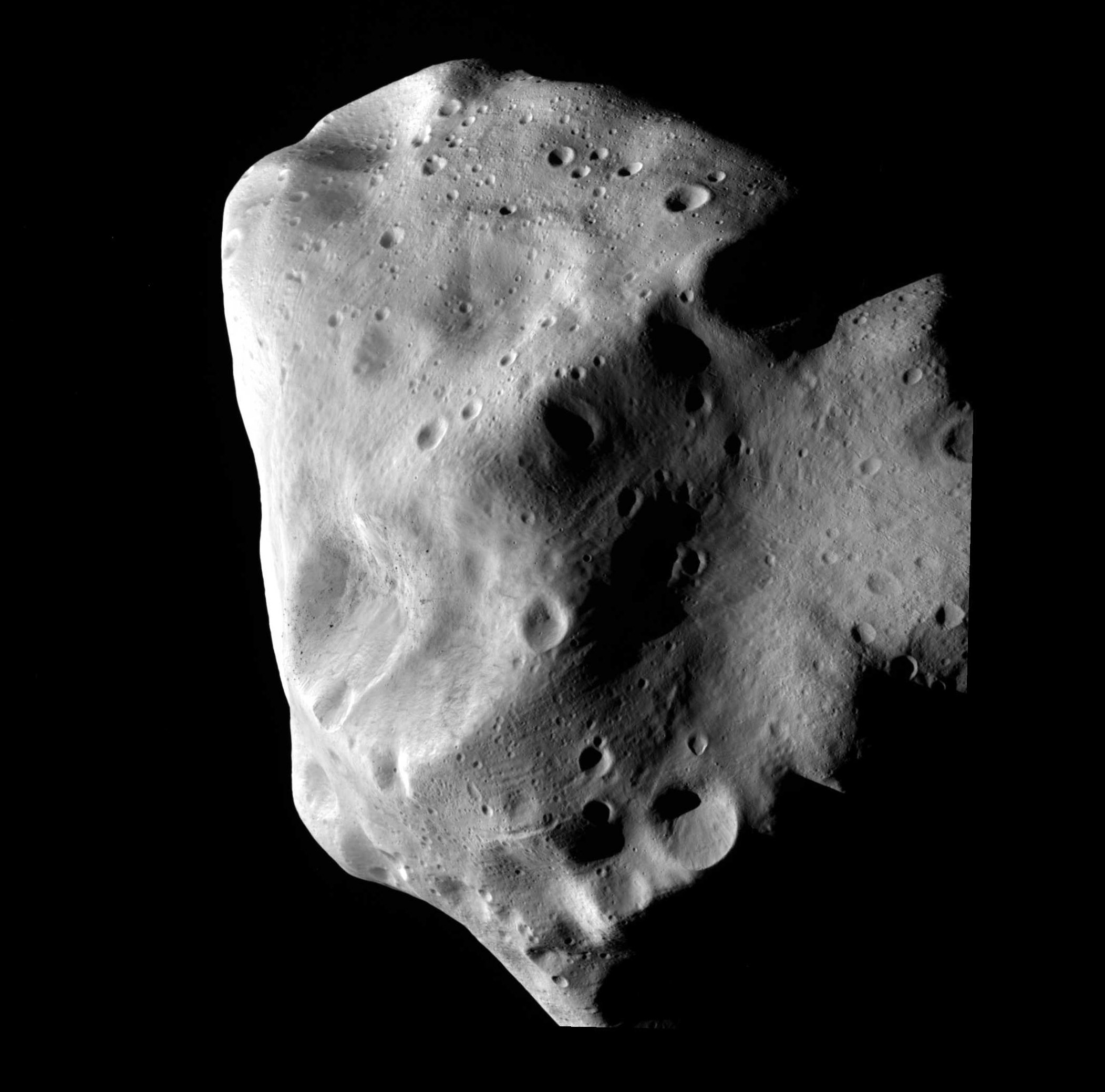

Kinetic impactors are one way by which we might be able to alter an asteroid's path. In principle, this technique requires smacking an asteroid to change its orbit around the sun so it no longer is a threat to Earth. Some asteroids may be loose piles of rubble that wouldn't be suitable for this technique, but on a solid rock this might work.

NASA plans to test out a kinetic impact with its Double Asteroid Redirect Mission (DART), which will slam into a small moonlet (Dimorphos) of the asteroid Didymos on Sept. 26. A few years later, a European Space Agency mission will fly to the system to look at the changes up close, while astronomers assess whether the moonlet's orbit changed in telescopes.

Related: NASA's DART asteroid-impact mission explained in pictures

Tractor beam

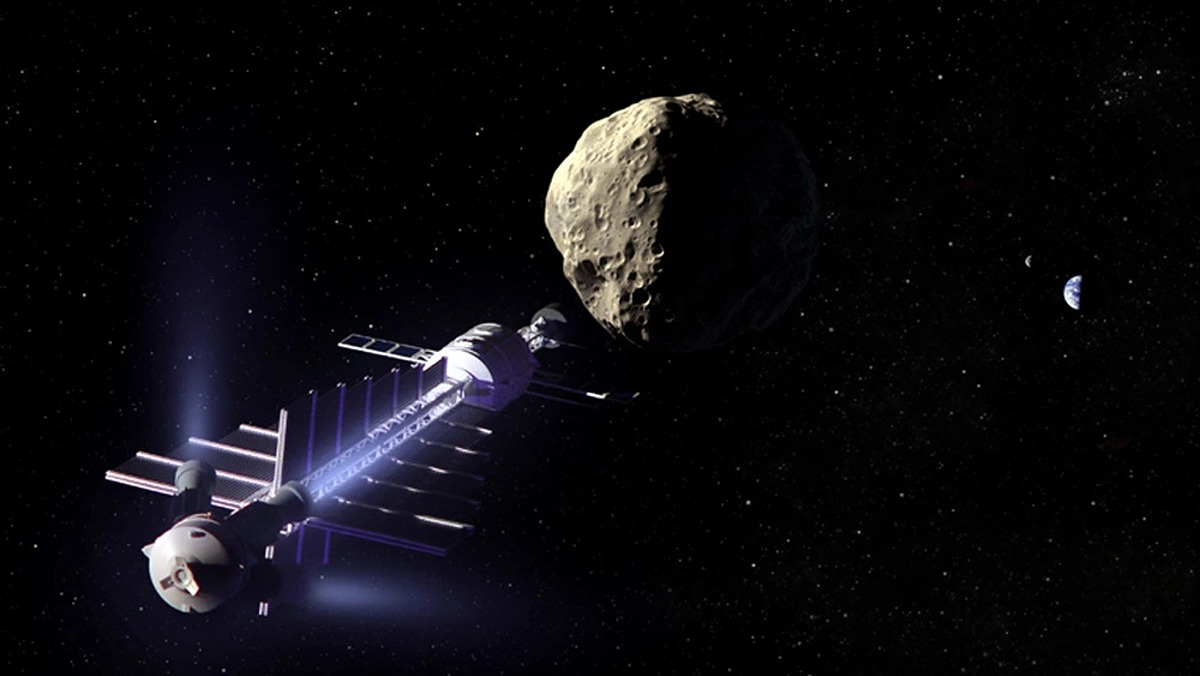

A gravity tractor asteroid deflection method seems to borrow from science fiction scenarios seen in "Star Wars" and "Star Trek," among many other space franchises. Compared to science fiction, however, a real gravity tug would proceed more slowly.

A robotic probe would meet up with a space rock and accompany it for at least several months, potentially years. Over time, the spacecraft's gravity would adjust the orbit of the asteroid. The more massive the probe, the stronger its gravitational pull would be and the faster the orbit would move.

In pictures: Check out NASA's asteroid-catching robot arms

Nuclear weapon

If scientists spot a hazardous space rock at the last minute, a nuclear bomb would likely be the only feasible choice. That's a technology that already exists and, with some adaptations, a rocket armed with a warhead could launch from a conventional launch pad within a relatively short period.

The key to a successful deflection will be to detonate the weapon a few hundred feet (or meters) away from the surface, not to impact it directly. If executed at the proper distance, the explosion would make the surface of the asteroid rip away into space and push the asteroid firmly away from its current path, experts have said.

Related: Here's the right way to nuke an asteroid (sorry, Bruce Willis)

Spray-painting

More leisurely options for asteroid deflection also exist. Spray-painting an asteroid takes advantage of the properties of albedo. Darker surfaces tend to reflect less; lighter surfaces tend to reflect more.

It would take many years, perhaps decades, for the effect to be noticeable, but it's something that happens naturally anyway. Scientists study the Yarkovsky effect, which is how sunlight slowly alters the path of asteroids as they go around the sun. If the scheme actually works, proponents say, spray-painting might be an inexpensive way to save Earth.

Related: Spray-painting asteroids could protect Earth from space rock threat

Ion propulsion

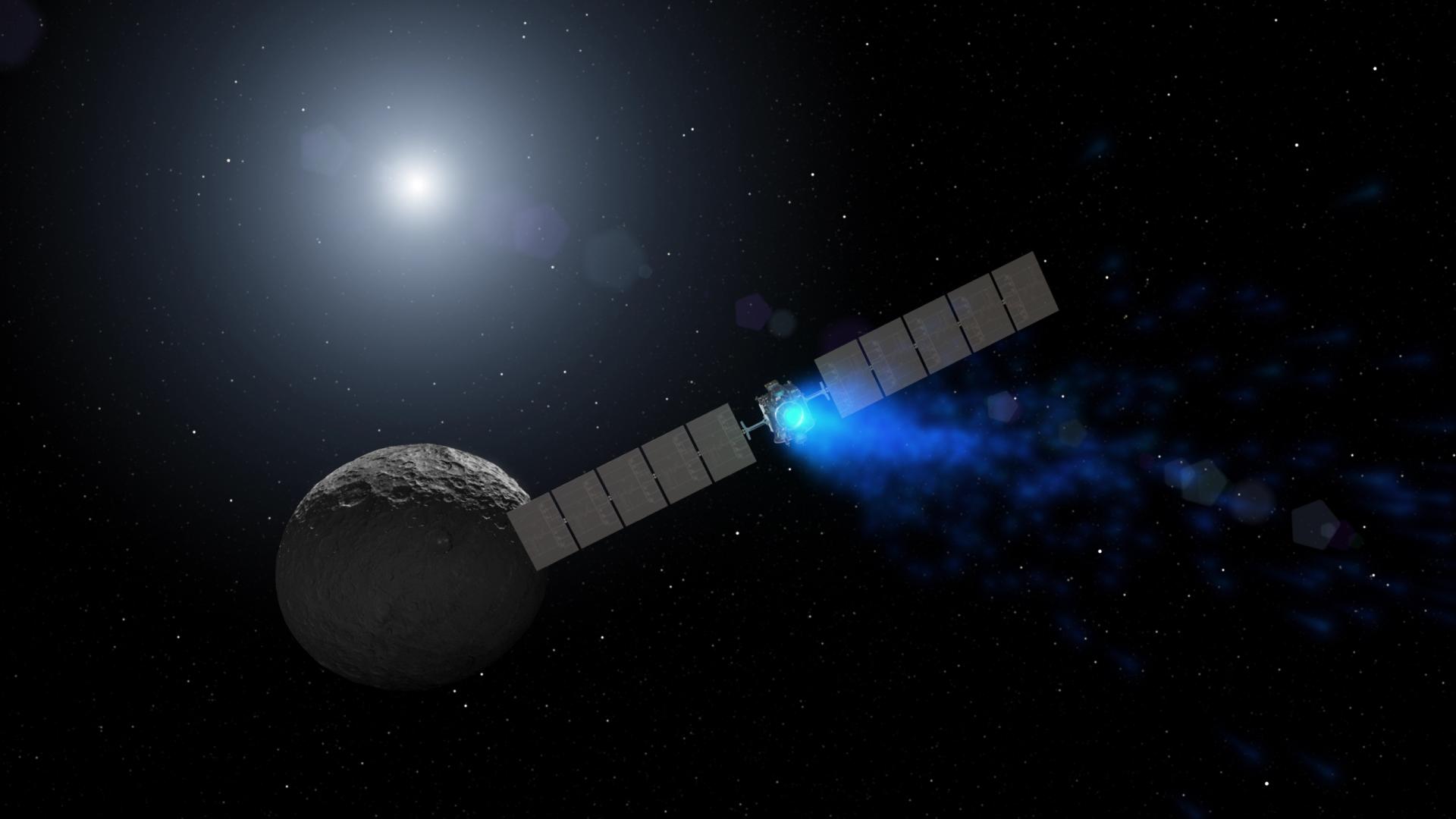

Using ion propulsion, or propulsion that uses charged or electrified molecules, is a variation of the gravity tractor effect that may be inexpensive. This kind of propulsion is very small, but builds up over time as there is no friction in space.

Ion propulsion also has been tested numerous times already. A good example is NASA's Dawn spacecraft, which did so well in its mission that it visited two space rocks (Ceres and Vesta) during its mission.

Related: How an ion drive Helped NASA's Dawn probe visit dwarf planet Ceres

Laser ablation

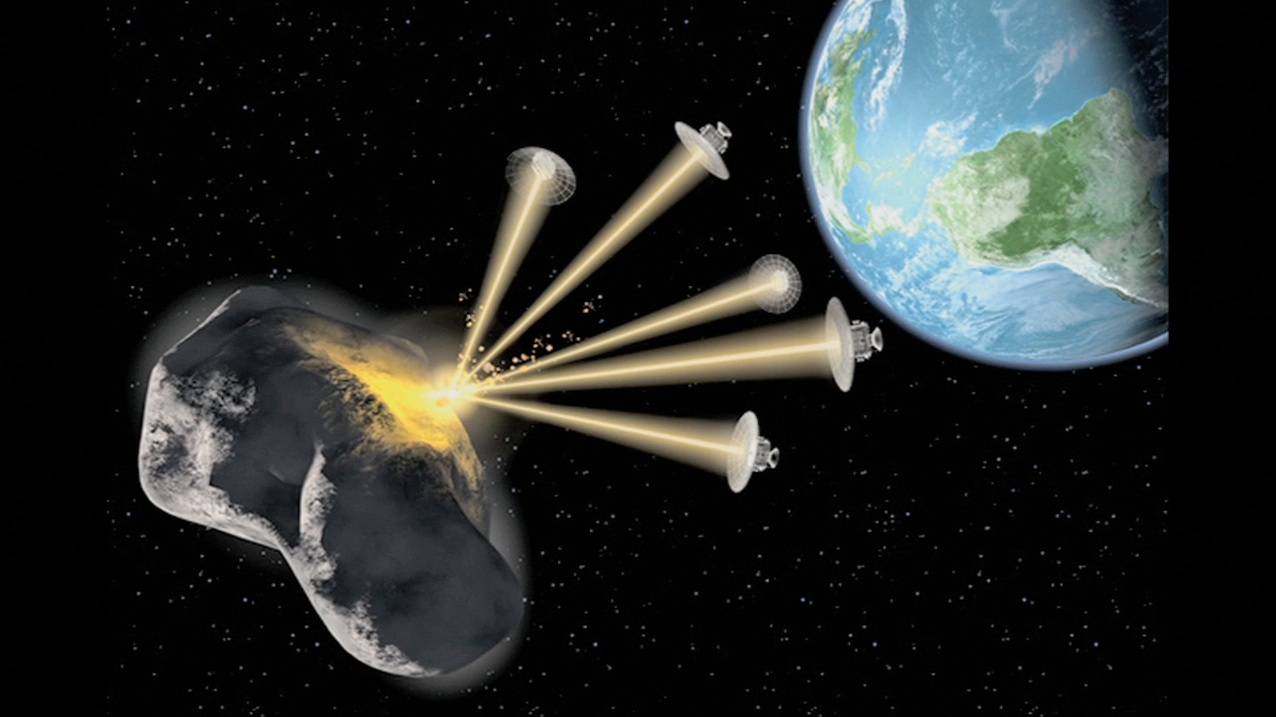

Turning to a more out-there scenario, laser ablation is another potential way to move asteroids around. Spacecraft, perhaps even little cubesats, would surround an asteroid and strategically laser a part of its surface. The ablation, or removal, of surface material would cause the asteroid to drift in the opposite direction.

Lasers are no stranger to space, but not on such a large scale. We're more used to lasers used by Mars rovers like Curiosity and Perseverance to assess the properties of rocks. Getting the laser to move the rock is another technology hurdle altogether.

Related: Wild Apophis asteroid spacecraft concept would loft tiny, laser-driven probes for 2029 flyby

Asteroid tether

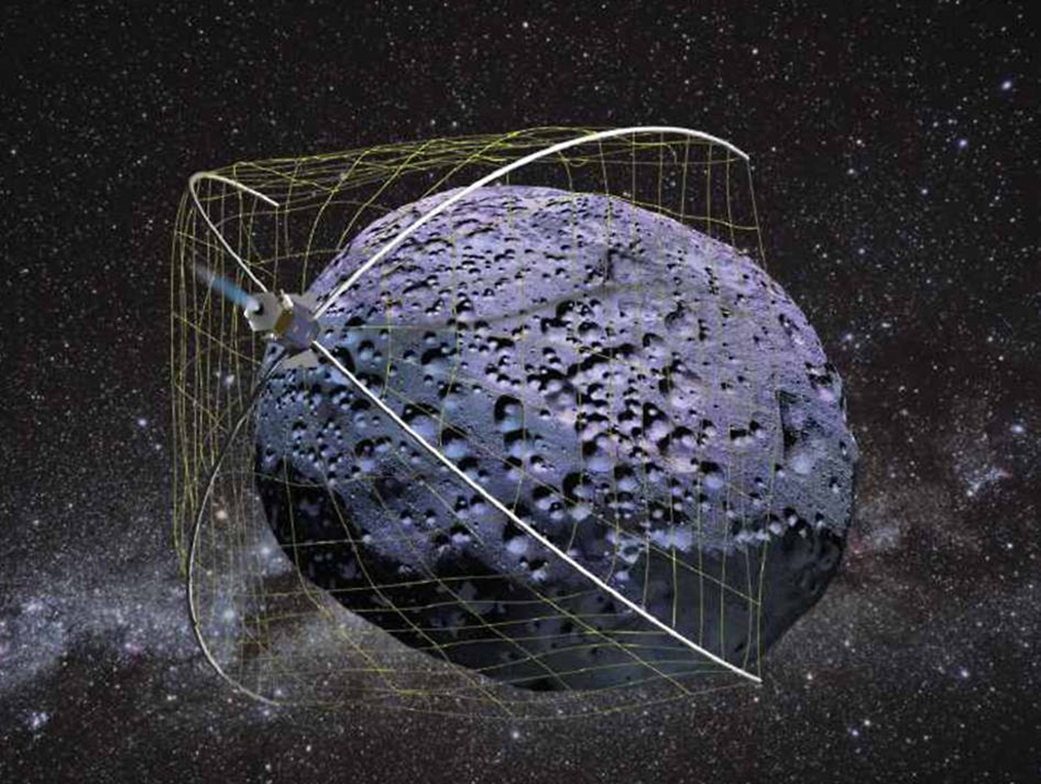

Tethering an asteroid sounds simple in principle, although there are a lot of questions to figure out how to tow it. What kind of material should form the web? How strong does it need to be? How do we use spacecraft to nudge the asteroid out of its orbit? This idea, therefore, is still pretty hypothetical.

NASA awarded a future tech contract in 2014 to assess how well tethers may move around asteroids and space debris. (It was called the called the Weightless Rendezvous And Net Grapple to Limit Excess Rotation system, or WRANGLER.) In the near term, we might be able to test out the plans on satellites that are much closer to Earth — with a side benefit of cleaning up hazardous space junk in low Earth orbit.

Bruce Willis

The Bruce Willis technique from "Armageddon" (1998) is probably our favorite, although it's highly unrealistic. Willis plays Harry Stamper, an oil miner by trade, who leads a group of unlikely astronauts, mostly colleagues from his oil rig. They fly out to a hazardous asteroid and try to drill deep in the surface; once the probe is deep enough, the story goes, a nuke should be enough to blow the asteroid off course.

Stamper is determined to do the work well: "I have never, NEVER missed a depth that I have aimed for," he assures NASA and his team. But things don't exactly go to plan. The scheme likely wouldn't have worked anyway, as likely all the nuke would have done was blow up the asteroid into a cloud of debris still on track to hit Earth.

But if nothing else, Willis and his Hollywood team raised the profile of planetary defense high enough to get in the public eye. In the same year that "Armageddon" and the other big space asteroid film of that time, "Deep Impact," released, Congress directed NASA to find all of the near-Earth asteroids at least 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) wide that could pose an impact risk to Earth.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.