NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office: How They Detect Asteroids Early

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

On Asteroid Day, scientists joined NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office (PDCO) to discuss the different strategies for preventing a catastrophic asteroid impact.

NASA hosted the special live-stream broadcast on June 30 from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. The speakers emphasized early asteroid detection as a key area of focus in planetary defense to ensure Earth's safety from an asteroid impact.

For the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), it is essential that the planetary defense office find threats early, PDCO's Lindley Johnson said during the broadcast. Once planetary defense officers determine the size and mass of an asteroid, they can decide which devices to use to deflect it, in the event it is on a crash course for the planet. If it's heading for U.S. soil on short notice, FEMA would coordinate natural disaster preparations, according to Johnson. [Defenders of Planet Earth: Asteroid Hunters Scour Night Skies for Threats (Video)]

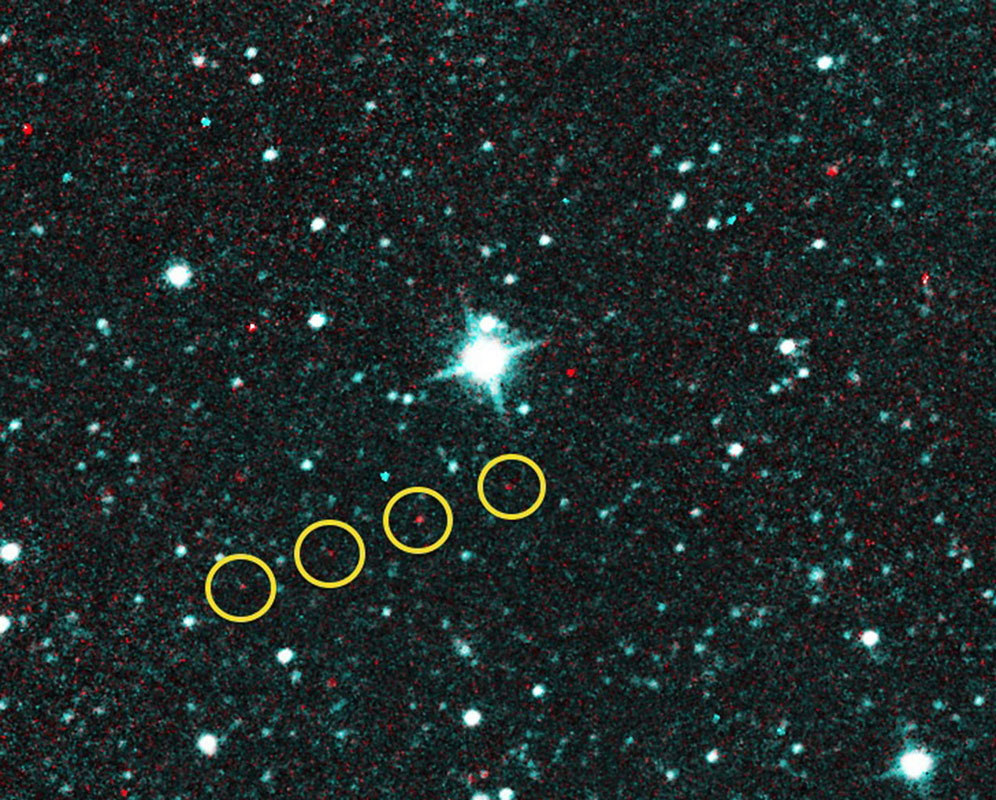

Article continues below"In any given night, the [International Astronomical Union's] Minor Planet Center receives something like 100,000 individual observations of asteroids," astrophysicist Matthew Holman said during the broadcast. Roughly 90 percent of those asteroids have already been seen in the sky, and their orbits have been precisely calculated. That means, Holman said, observers can "focus our attention on the remaining 10 percent and try to determine if those are potentially hazardous near-Earth objects or garden-variety main belt asteroids."

To put it into a reassuring perspective, the distance from Earth to the Main Asteroid Belt is more than two and a half times the distance between Earth and the sun.

To then determine if any new asteroids have orbits that would lead to impact with Earth, each asteroid's movement is compared to the constant of the background stars. Through the visual phenomena of parallax, something that's close-by appears to move faster than something that's located much farther away, even when they're moving at the same speed. The rate of motion of the asteroid is therefore used as a proxy for distance.

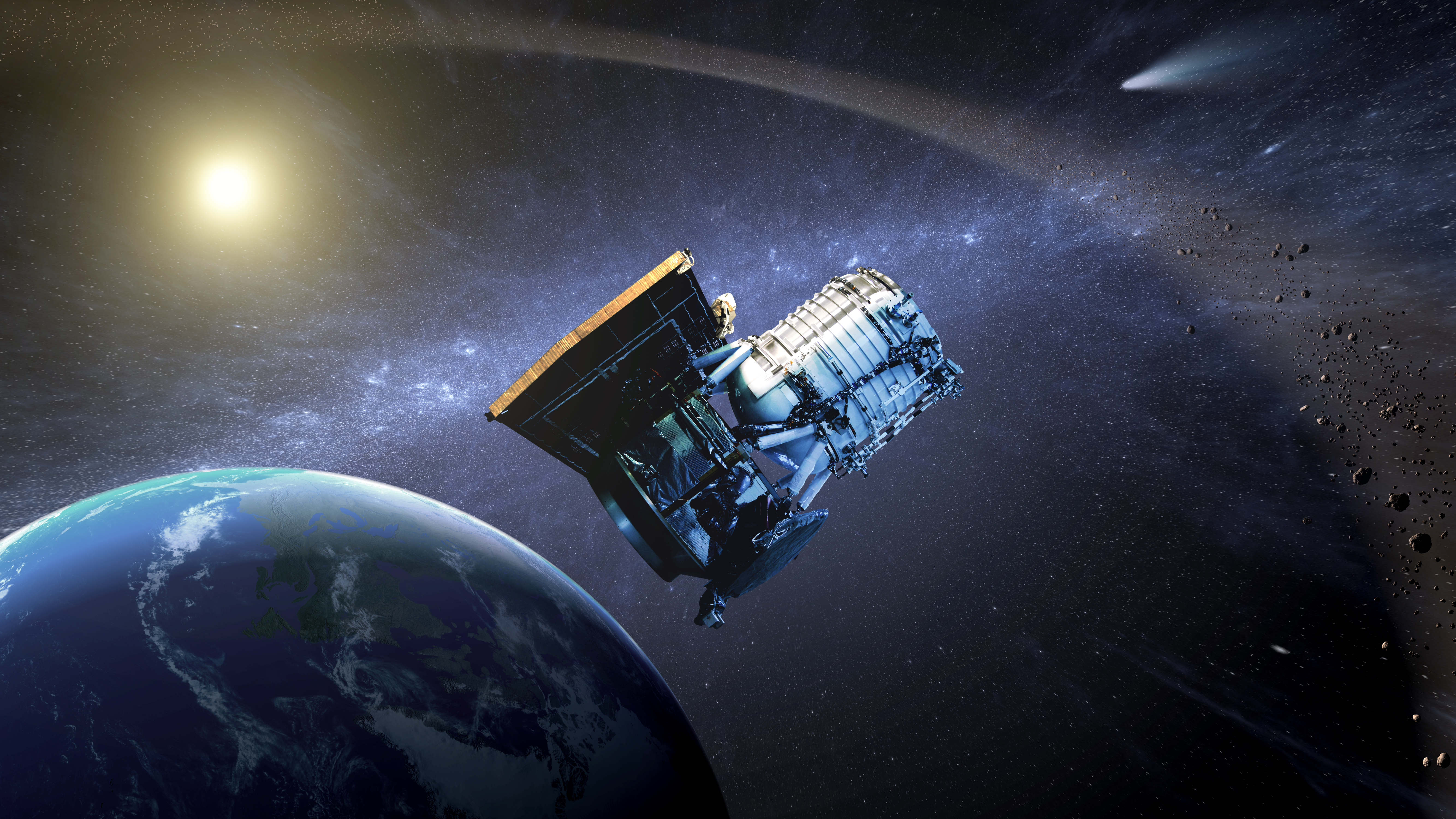

In the broadcast, Marina Brozovic of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory shared that radar is another great tool for asteroid detection. "Radar is a little bit like a Swiss army knife," she said. "It reveals so much about asteroids all at once."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Details like size, shape and whether an asteroid is a binary system — in which a smaller object orbits the larger asteroid — can be determined with radar technology, whereas optical detection is less accurate in measuring that kind of information.

But should an asteroid approach Earth for what would be a doomsday scenario, the PDCO has a course of action outlined to address the danger. Johnson cited two technologies the agency could use to avoid disaster: a kinetic impactor, which is a high-speed spacecraft that would run into an asteroid to nudge it from Earth's path, and a gravity tractor, a spacecraft that flies long-term alongside an asteroid and ultimately uses its own gravity to pull the asteroid off from Earth's path.

That said, telescopes are still key to documenting the numerous asteroids that pass by the Earth within relative proximity, the researchers said. One potential surprise is that NASA makes use of freelance and amateur astronomers to watch for near-Earth objects in the night sky. Bob Holmes, for instance, appeared in the broadcast and owns not one, but four of some of the largest privately owned telescopes in the world — and he keeps them trained on the skies to identify new asteroids.

During the broadcast, several people on social media shared their concerns that an impending impact would be withheld from the public. Dr. Kelly Fast of NASA's Solar System Observations program commented that there are websites where near-Earth object observations are available and constantly updated. Anyone with an internet connection can view these sites, Fast said.

The special broadcast on Asteroid Day also offered some interesting anecdotes. Dr. Eileen Ryan of the Magdalena Ridge Observatory in New Mexico spoke about an asteroid that once passed through Earth's geosynchronous satellite zone, the highest orbit for satellites, and flew by one of NASA's communications satellites.

An asteroid is normally named based on the year and the two-week period when the space rock was discovered, the researchers said. In special instances, however, asteroids and minor planets can be given a human name in honor of someone. Asteroid 316201 Malala, for example, was named after Malala Yousafzai, the Nobel Peace Prize recipient of 2014 because, said JPL's Amy Mainzer, "She's awesome! She needs an asteroid."

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.