Lunar love affair: Enjoying the beauty of the moon

For many of us, it all started with the moon.

If there was one object in the night sky that first attracted me to astronomy as a very young boy, it was the moon. I strongly suspect that is how it was with others who have had a lifelong interest in this particular branch of science. Many astronomers, I feel sure, began their lifework as sensitive children who responded to the thrill of a experiencing an eclipse or who were awed by witnessing the colors of a spectacular sunset or seeing brilliant Venus glowing like a night light against a cobalt twilight sky.

But the moon, which sometimes would appear to me large and bloated as it hazily came over the horizon on a summer's evening, or shone small and brilliant as it ascended high into the sky on cold, winter nights is an attraction all its own.

Related: What is the moon phase today? Lunar phases 2023

Read more: How to photograph the moon

One of the most complex of all astronomical problems is calculating the motion of the moon. Ernest William Brown (1866 — 1938) was an English mathematician and astronomer, whose life's work was the study of the moon's motion and the compilation of extremely accurate lunar tables. But knowledge of such complex mathematics need not concern those of us who simply enjoy watching the ever-recurring lunar phases and the various circumstances of the moon with relation to the horizon, the stars and the planets during each month.

About 29.5 days elapse from one new moon to the next. At new phase the moon is in the same region of the sky as is the sun and cannot be seen (unless it passes directly in front of the sun to produce a solar eclipse). This 29.5-day interval is known as a synodic month, taken from the Greek word synodos meaning "meeting," for at new moon the moon "meets" the sun.

Meniscus moon

Want to see the features of the moon up close? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide. Don't forget a moon filter!

Our first view of the moon after new phase usually comes a couple of days later as a delicately thin arc of light enclosing a ghostly ball. This was the signal by which ancient sky watchers set their calendars.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For about a week after new moon, sunlight reflected from the Earth illuminates the night side of moon, making its whole disk visible and fitting the old saying, "the old moon in the new moon's arms." If we were astronauts on the dark part of the moon looking up at the sky, the sun would not be above the horizon but the Earth would, and like the moon, we would see it go through phases. But a crescent moon for us, equates to a nearly full Earth as seen from the moon. And because the Earth appears nearly four times larger than the moon and is a planet covered by oceans and clouds which are very effective reflectors of sunlight, the Earth appears dozens of times brighter than a nearly full moon and readily illuminates the lunar landscape with an eerie bluish-gray hue.

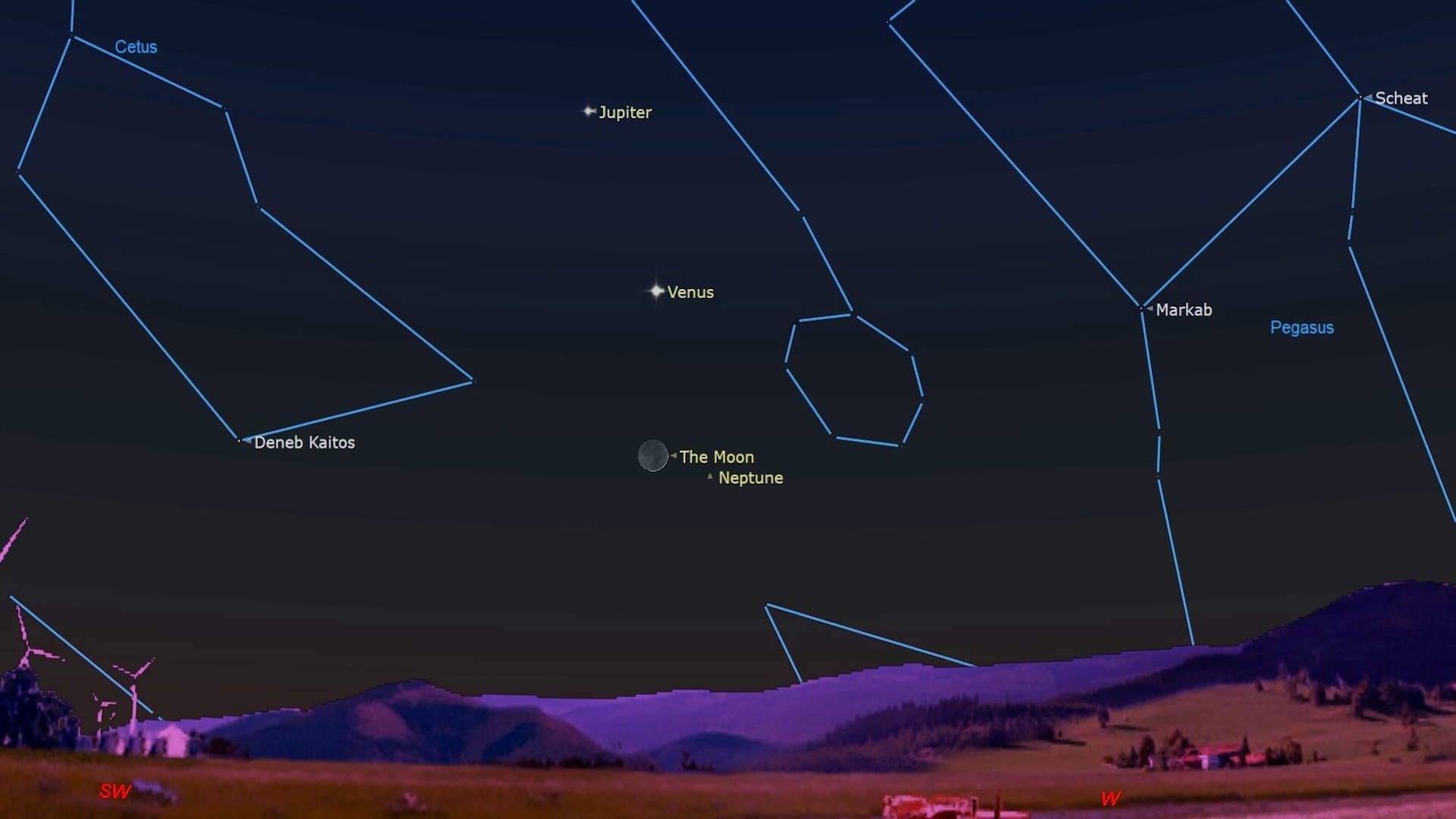

Here is one of nature's beautiful sights, easily seen by most anyone but far-better appreciated by those who know the stage setting that makes it possible. Be sure to look this "Earthshine" on the evenings of Feb. 21 and 22, when the moon will be in the general vicinity of the planets Venus and Jupiter.

A cup, boat or a smile

Season of the year and observer's latitude determine the angle a line joining the crescent moon's tips or cusps makes with the horizon, when the moon is not very high in the sky. During February, March and April this line is more nearly horizontal, making the crescent look like a cup that might hold water — farmers especially, would refer to this as a "wet moon."

In his book, Mathematical Astronomy Morsels IV (Willmann-Bell, Inc. 2007), Jean Meeus included a chapter, "The moon as a boat," in which the lunar cusps can appear exactly horizontal on occasions even from locations well north of the equator. Most of the time for mid-northern latitudes (as will be the case on February 21-22), the crescent appears tilted somewhat to the left. Farther south, however, it's a different story. For residents of Florida from Orlando southward, and in Texas around Corpus Christi and Laredo, those same crescent moons will appear quite horizontal.

Before the sky darkens sufficiently to see Earthshine, as when just the crescent is visible against the blank blue sky, it will resemble a smile like the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland.

Let's straighten this out

Growing in phase each night and increasing in brightness, the moon finally forms a neat half disk. At the moment of first-quarter phase, the lunar terminator — the line that separates light and dark and divides day and night on the lunar surface — appears straight to our view; the long shadows cast by lunar mountains and crater rims, make fascinating watching in a small telescope as the sun rises over the quarter moon. Sometimes within just a few minutes we can see illumination suddenly strike the summit of a lunar mountain. The shadow of a peak near the terminator can shorten noticeably from hour to hour.

It is not always possible, however, to see the terminator straight when an almanac predicts the moment of first quarter, for the moon may be below your horizon. This month, the time is 0806 Universal or Greenwich Time, or 3:06 a.m. in Boston on Feb. 27. The moon of Sunday evening, February 26th, will still be a crescent, with a concave terminator; the next night the phase will be gibbous and the terminator noticeably convex.

Not until March 29 at 0232 Universal Time (9:32 p.m. CST on the 28) will all American observers see the moon at the moment of first quarter with the terminator appearing straight and true.

The shifting moon

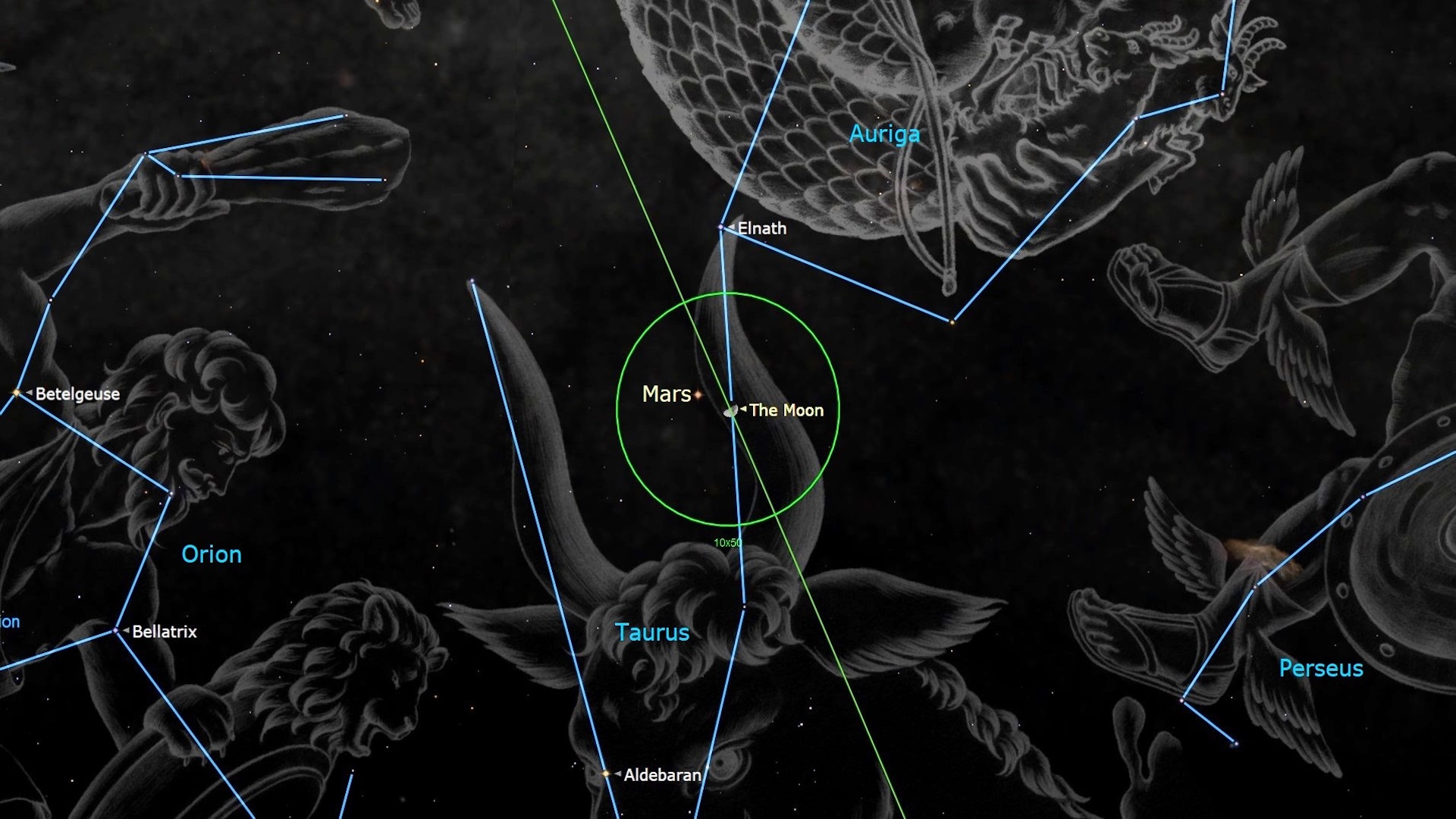

When the moon is near any bright star or planet, sometimes only a few minutes of watching will show its ongoing eastward motion. During the overnight hours of Feb. 27 and 28, we can watch as the waxing gibbous moon slowly approaches from the west and then passes just above the planet Mars.

From New York, as darkness falls, Mars will appear more than two degrees to the left of the moon and yet later that night at around 1:00 a.m., the moon will be hovering less than a half degree to the upper right of Mars. Unlike the Mars-moon encounters in December and January where parts of the United States could watch the moon pass in front of Mars, in February, an occultation will be available only to those living near the polar regions, namely northern Scandinavia, Svalbard, northwest Greenland, Iceland and the Faroe Islands.

Full or not full?

So far as a full moon is concerned, sometimes you have to be careful in determining exactly when the lunar disk is fully illuminated. In March, for example, full moon will occur around, or just prior to sunrise across the United States on Tuesday (March 7). Those who check calendars or newspapers that provide dates for the phases of the moon will see the notation for a full moon on March 7, but if they look up into the sky that night, they will actually be looking at a waning gibbous moon, as the time of the occurrence of when the moon was truly "full" actually occurred more than half a day earlier. Look carefully at the moon that Tuesday night (March 7) — especially with binoculars or a small telescope — and you'll probably be able to detect an ever-so-slight "out of roundness;" a thin crescent of darkness, on the right side of the lunar disk.

But because it will be only several days past maximum distance from the Earth (apogee), the moon will be traveling relatively slowly in its orbit; both effects will combine to make its motion across the sky especially small from night to night. As a consequence, many who look at the moon on the evening of the March 7, with just their bare eyes, might insist it looks full to them. In fact, some might even say that the moon still looks full to them on Wednesday (March 8)! The defect of illumination on the moon's disk — that dark sliver along its edge — will be very slight on both, the nights of March 6 and 8.

In contrast, when the moon turns full on the evening of Aug. 30, it will nearly coincide with perigee, its closest point to Earth (the so-called "supermoon"). At that time, the moon will be moving more rapidly in its orbit and the change in overall illumination across the lunar disk will be much more rapid. As a result, even a casual observer should be able to see that on the nights immediately flanking Aug. 30, that the moon will appear not quite full.

So, if someone remarks to you that the moon looks full on Aug. 29 or 31, just tell them they are just i-moon-gining it!

If you can't get enough of moonwatching and want to get into lunar photography, be sure not to miss our guide on how to photograph the moon for the best lunar photography tips and tricks we've found. We also have guides on the best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography if you need to gear up for this or other celestial events.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.