Mars may be wetter than we thought (but still not that habitable)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Mars is wetter than previously thought, but not in a way that boosts its life-hosting potential, a new study suggests.

Liquid fresh water can't exist for long on the frigid Martian surface; the stuff quickly freezes or boils away into the planet's thin atmosphere. But brines — supersalty water — have much lower freezing points and can persist in liquid form on the Red Planet for longer stretches.

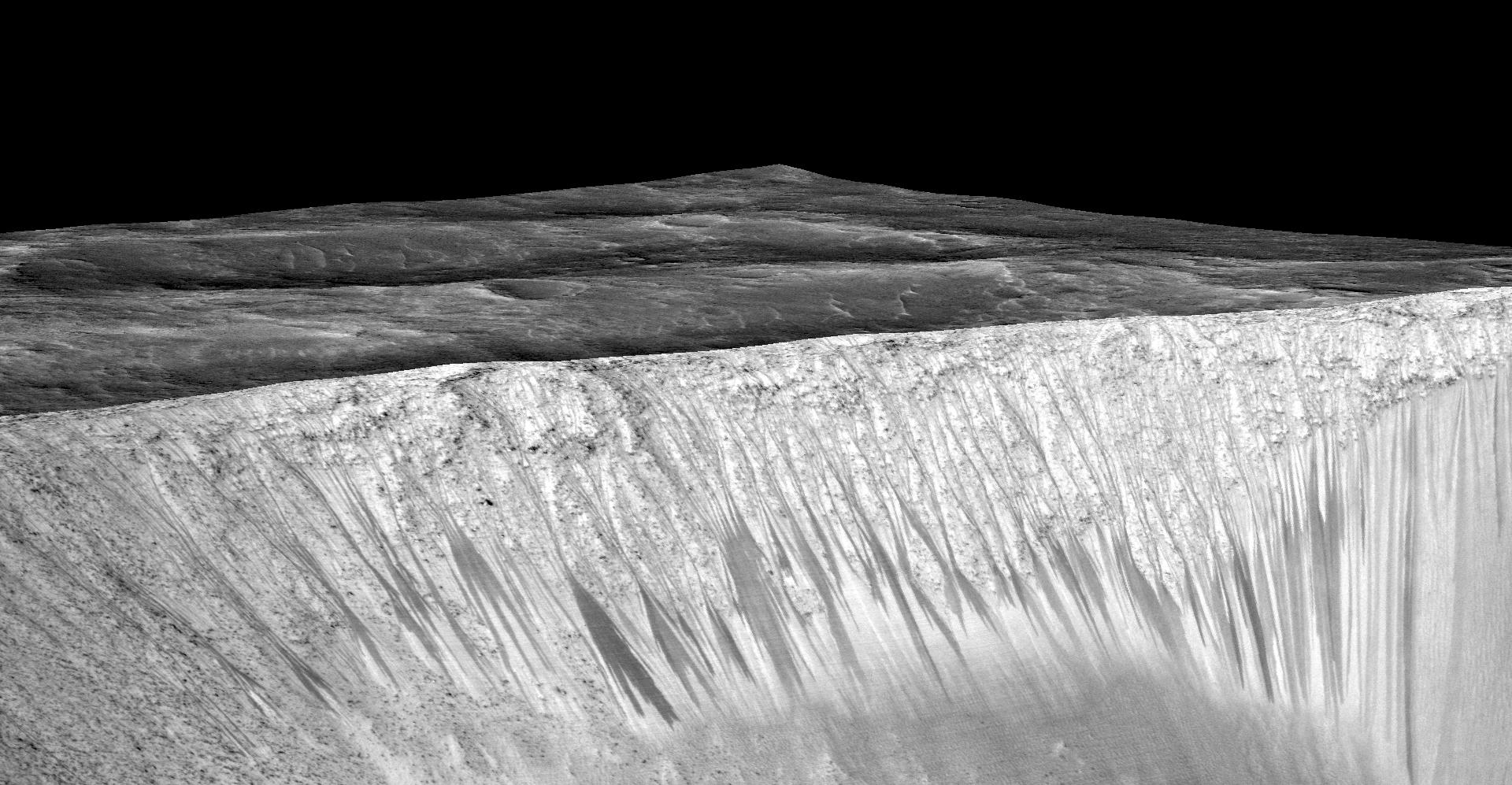

Scientists have seen possible evidence of such liquid brines over the years in the form of dark streaks on warm Red Planet slopes imaged by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. (Not everyone is convinced that liquid water is involved in the formation of these "recurring slope lineae," however.)

In the new study, researchers used measurements gathered by Mars-studying spacecraft and information from atmospheric models to devise a new model, which predicts where liquid brines could exist at and near the Martian surface.

Related: The search for water on Mars in photos

That model indicates that up to 40% of Mars could support liquid surface brines for perhaps six hours at a time. This is a distinctly seasonal phenomenon, with brines in each location possible during just 2% or so of the year, study team members said. (One Mars year lasts for 687 Earth days.)

The near subsurface is likely wetter still: the model suggests that brines could exist during 10% of the Martian year at a depth of about 3 inches (8 centimeters). (And the deep subsurface may be very wet indeed; Europe's Mars Express spacecraft recently detected evidence of a big lake beneath the Red Planet's south pole.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But these brines aren't promising abodes for life as we know it: they're likely ultracold, with maximum temperatures around minus 55 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 48 degrees Celsius), the researchers said.

"Our results indicate that (meta)stable brines on the Martian surface and its shallow subsurface (a few centimeters deep) are not habitable because their water activities and temperatures fall outside the known tolerances for terrestrial life," they wrote in the new study, which was published online Monday (May 11) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

There's a silver lining in this astrobiological dark cloud, however. Because these brines apparently cannot support Earth-like life, future Mars missions should be able to investigate them and surrounding areas without worrying too much about contaminating them with microbes from our world, study team members said.

"These new results reduce some of the risk of exploring the Red Planet while also contributing to future work on the potential for habitable conditions on Mars," co-author Alejandro Soto, a senior research scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said in a statement.

Mars was very different in the distant past than it is today. The ancient Red Planet featured a thick atmosphere and lots of surface water, including, some scientists believe, a huge ocean that covered perhaps 40% of its northern hemisphere. But things changed dramatically about 4 billion years ago, when Mars lost its global magnetic field and particles from the sun began stripping away the planet's air.

- Water on Mars: Exploration and evidence

- Could there be life on Mars today?

- 7 biggest mysteries of Mars

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.