Water on Mars? Boulder shadows may spawn short-lived pools of brine.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Many tiny patches of the ground on modern Mars may be capable of supporting life as we know it, if only very briefly, a new study suggests.

Water ice is abundant on and near the Martian surface, but conditions have to be just right for this stuff to give rise to liquid water. That's because the Red Planet's atmosphere is quite thin — just 1% as dense as Earth's air at sea level — so ice tends to sublimate, or turn directly into vapor, when temperatures rise sufficiently. (Specifically, the ice evaporates before temperatures rise enough to hit water's melting point.)

The study identifies a microenvironment that could host those just-right conditions: the areas directly behind certain boulders in midlatitude regions of Mars that lie in the rocks' shadows continuously during the winter months.

Related: Photos: The search for water on Mars

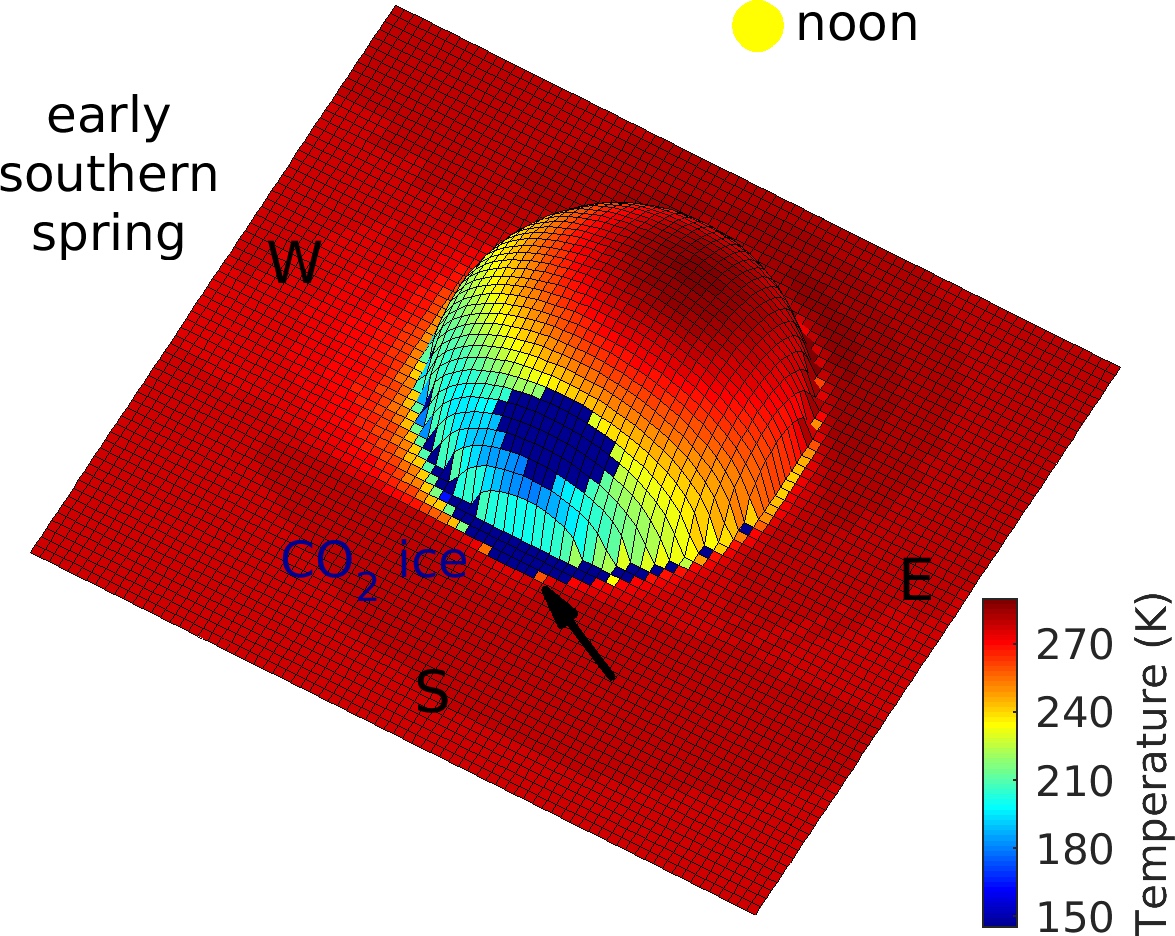

Water ice and carbon-dioxide ice accumulate seasonally in these shadowy spots, according to computer simulations performed by study author Norbert Schorghofer, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona.

When spring comes and sunlight hits these microenvironments again, temperatures there rise rapidly, from about minus 198 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 128 degrees Celsius) to 14 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 10 degrees Celsius) in just a few hours. The ice fades away, but the temperature transition is so fast that not all of the ice sublimates; some melts into the salty Martian soil, forming liquid brines.

The soil's saltiness is key to this process, because salt lowers the melting point of water to less than the usual 32 degrees Fahrenheit (0 degrees Celsius). And the carbon-dioxide ice also appears to help things along.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Dust contained in the CO2 frost facilitates the formation of a protective sublimation lag," Schorghofer wrote in the paper, which was published online Wednesday (Feb. 12) in The Astrophysical Journal.

"Overall, melting of pure water ice is not expected under present-day Mars conditions," he added. "However, at temperatures that are readily reached, seasonal water frost can melt on a salt-rich substrate."

Brine formation may last for just a few days in each locale that experiences it. But the phenomenon is a regular one, repeating every year, the study suggests.

Patches of winter boulder-shadow aren't the only parts of Mars that may experience seasonal surges of liquid water. NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has spotted dark features on multiple Red Planet slopes during the warmer months. Many researchers interpret these "recurring slope lineae" to be evidence of temporary brine flows, but other scientists argue that liquid water may not be involved.

Liquid water was abundant on Mars billions of years ago, when the planet still had a protective magnetic field and a much thicker atmosphere. Indeed, NASA's Curiosity rover has determined that its landing site, the floor of the 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater, hosted a long-lived lake-and-stream system in the ancient past.

And there may still be lots of water underground on the Red Planet today. For example, Europe's Mars Express spacecraft recently spotted evidence of a huge lake beneath the planet's south pole.

- Water on Mars: Exploration and evidence

- Could there be life on Mars today?

- 7 biggest mysteries of Mars

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.