What's next for India's Chandrayaan-3 moon rover mission?

India's third lunar exploration mission lifted off on Friday (July 14) and is set to arrive at the moon in late August.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

India's third lunar exploration mission, Chandrayaan-3, has embarked upon its historic and circuitous journey to the moon.

Chandrayaan-3, which consists of a propulsion unit and a robotic lander and rover, launched from India's Satish Dhawan Space Centre early Friday morning (July 14). The mission will land on the moon on Aug. 23 or Aug. 24, if all goes according to plan.

Success would be huge for India, making it the fourth nation — after the Soviet Union, the United States and China — to soft-land a probe on the moon.

According to Chandrayaan-3's operators, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), the three main objectives of the roughly $77 million USD mission are to perform a safe soft landing near the lunar south pole, to deploy a rover and demonstrate its operation and to perform in-situ scientific experiments over the course of a single lunar day of operation (equivalent to about 14 Earth days).

But there's a lot to do before Chandrayaan-3 reaches the moon. Here's a brief rundown of those next steps.

Related: Chandrayaan-3: A guide to India's third mission to the moon

Chandrayaan-3's 6-week journey from Earth to the moon

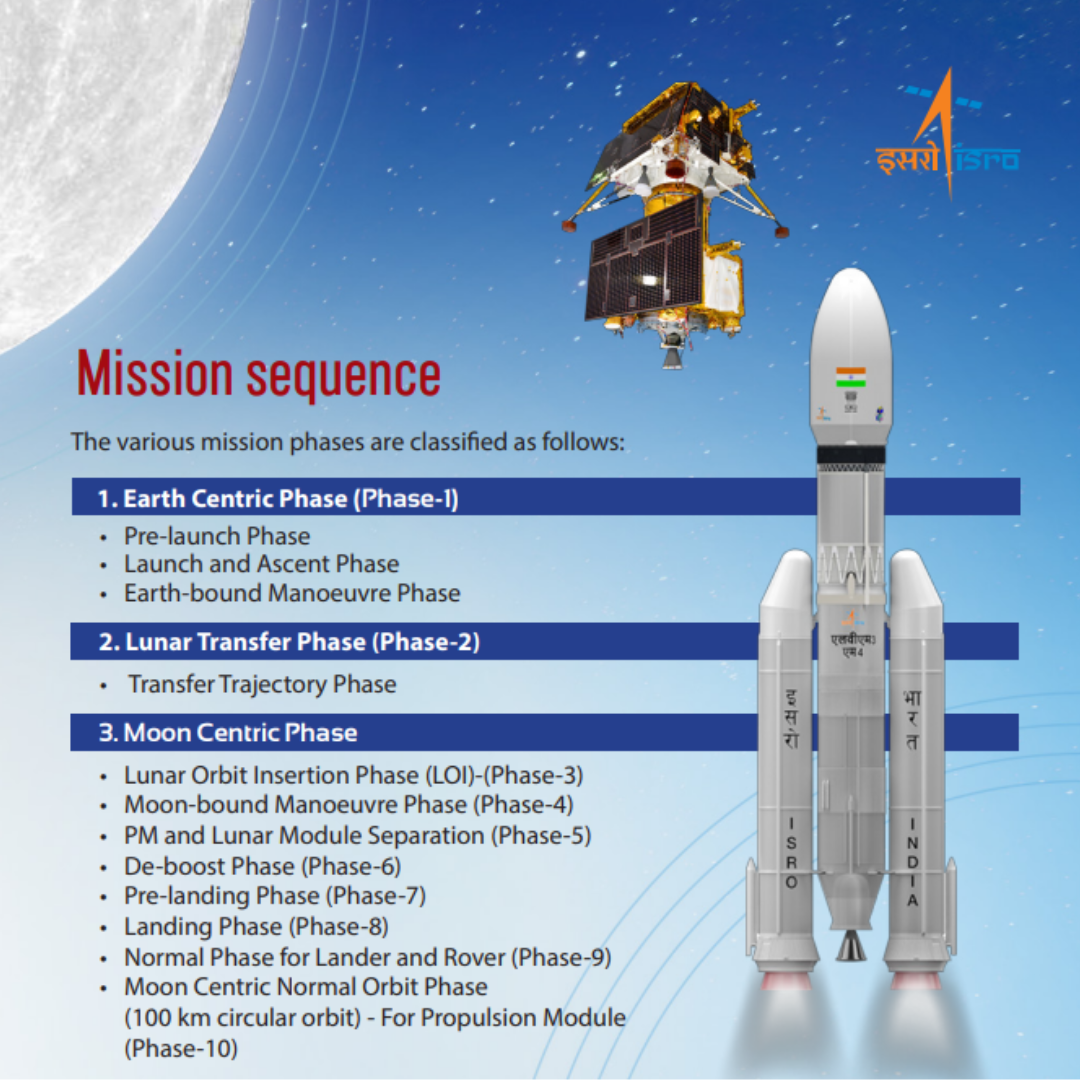

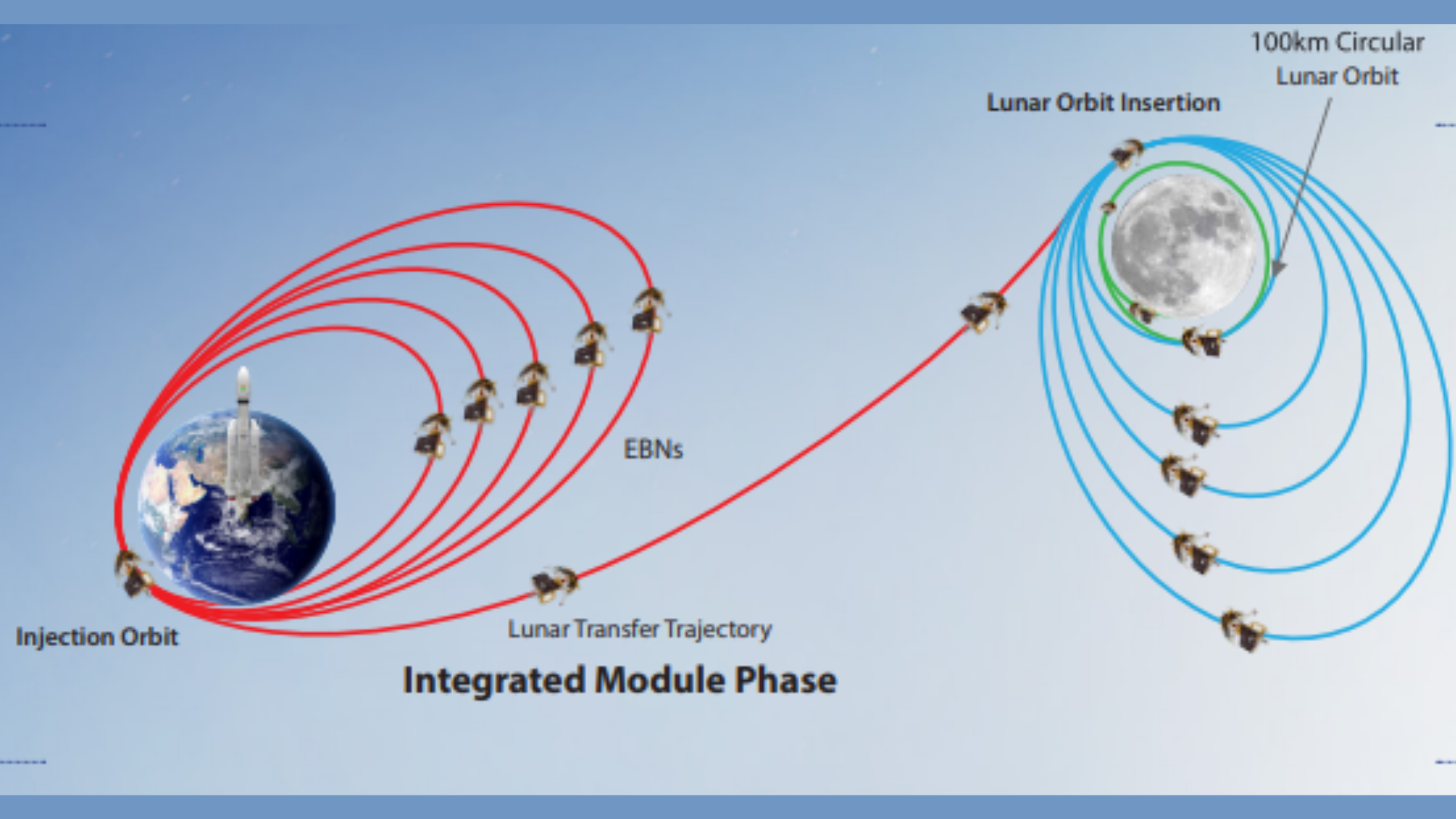

ISRO divides Chandrayaan-3's roughly 40-day journey to the moon into three distinct segments: the Earth-centric phase, the lunar transfer phase and the moon-centric phase.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Phase 1 is now partially over, with the prelaunch and launch and ascent periods completed by liftoff and the separation of Chandrayaan-3 from its rocket. The mission is now in the Earth-bound maneuver stage, which is part of Phase 1.

During this chapter, Chandrayaan-3 will make five orbits around Earth. Each time it swings past Earth, the spacecraft will increase its distance from our planet. The final sweep will help place Chandrayaan-3 on a lunar transfer trajectory, sending it moonward during the lunar transfer phase (Phase 2).

Chandrayaan-3 will next insert itself into lunar orbit, a move that will kick off the moon-centric phase (Phase 3). The mission will then orbit the moon four times, getting gradually closer to the lunar surface with each subsequent loop.

Chandrayaan-3 can't just head straight from an Earth orbit to landing on the moon.

When spacecraft return to Earth from space, they have our planet's atmosphere dragging on them and slowing their descent. But the moon has an incredibly wispy atmosphere, so to make a lunar landing, spacecraft have to slow themselves and make a much more gradual approach.

Related: Missions to the moon: Past, present and future

Chandrayaan-3 will perform an engine burn that moves the craft into a circular orbit around 62 miles (100 kilometers) above the lunar surface. The lander and rover elements of the mission will then separate from the propulsion module.

The lander will touch down in the south polar region of the moon, at a speed of under 5 mph (8 kph). The propulsion module of Chandrayaan-3 will stay in orbit around the moon, remaining in communication with the rover and the lander.

The Chandrayaan-3 vehicles will also use the orbiter from the Chandrayaan-2 mission, which arrived at the moon in 2019, as a backup communications relay. Chandrayaan-2 also featured a lander-rover duo, but they crashed during their lunar touchdown attempt in September 2019.

What's next on the moon?

ISRO Chairman Sreedhara Panicker Somanath explained to the Times of India why Chandrayaan-3's solar-powered lander and rover are touching down in late August.

"Landing will be on August 23 or 24, as we want the landing to happen when the sun rises on the moon, so we get 14 to 15 days to work," he said. "If landing cannot happen on these two dates, we'll wait for another month and land in September."

The Chandrayaan-3 lander has its own thruster system, navigational and guidance controls, and hazard detection and avoidance systems.

ISRO has implemented several changes since the Chandrayaan-2 crash. Somanath told the Times of India that these improvements include the strengthening of the lander's legs, increases to its landing-speed tolerance and the addition of new sensors to measure approach speed.

Once a safe landing has been achieved, it will be time for the Chandrayaan-3 rover to roll out.

The rover is equipped with its own scientific payloads to investigate the moon, including the LASER Induced Breakdown Spectroscope (LIBS), which allows for the analysis of the chemical composition of the lunar surface; and the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS), which will do the same for lunar rocks and soil around the Chandrayaan-3 landing site.

As the rover goes about its business, the lander that carried it down to the surface will do its own science work. The lander will use the Radio Anatomy of Moon Bound Hypersensitive Ionosphere and Atmosphere (RAMBHA) instrument to measure plasma — a gas of electrons and ions — at the lunar surface and how it changes over time.

Meanwhile, the lander's Chandra’s Surface Thermophysical Experiment (ChaSTE) will measure the thermal properties of the south polar region, and the

Instrument for Lunar Seismic Activity (ILSA) will measure the moon's seismicity to help flesh out the structure of the lunar crust and mantle.

As this is all taking place, a passive experiment called the LASER Retroreflector Array (LRA), contributed by NASA, will be running in the background on the lander, collecting data that could help scientists better understand the dynamics of the moon system.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.