Chandrayaan-2: India's Orbiter-Lander-Rover Mission

Reference Article: Facts about Chandrayaan-2.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

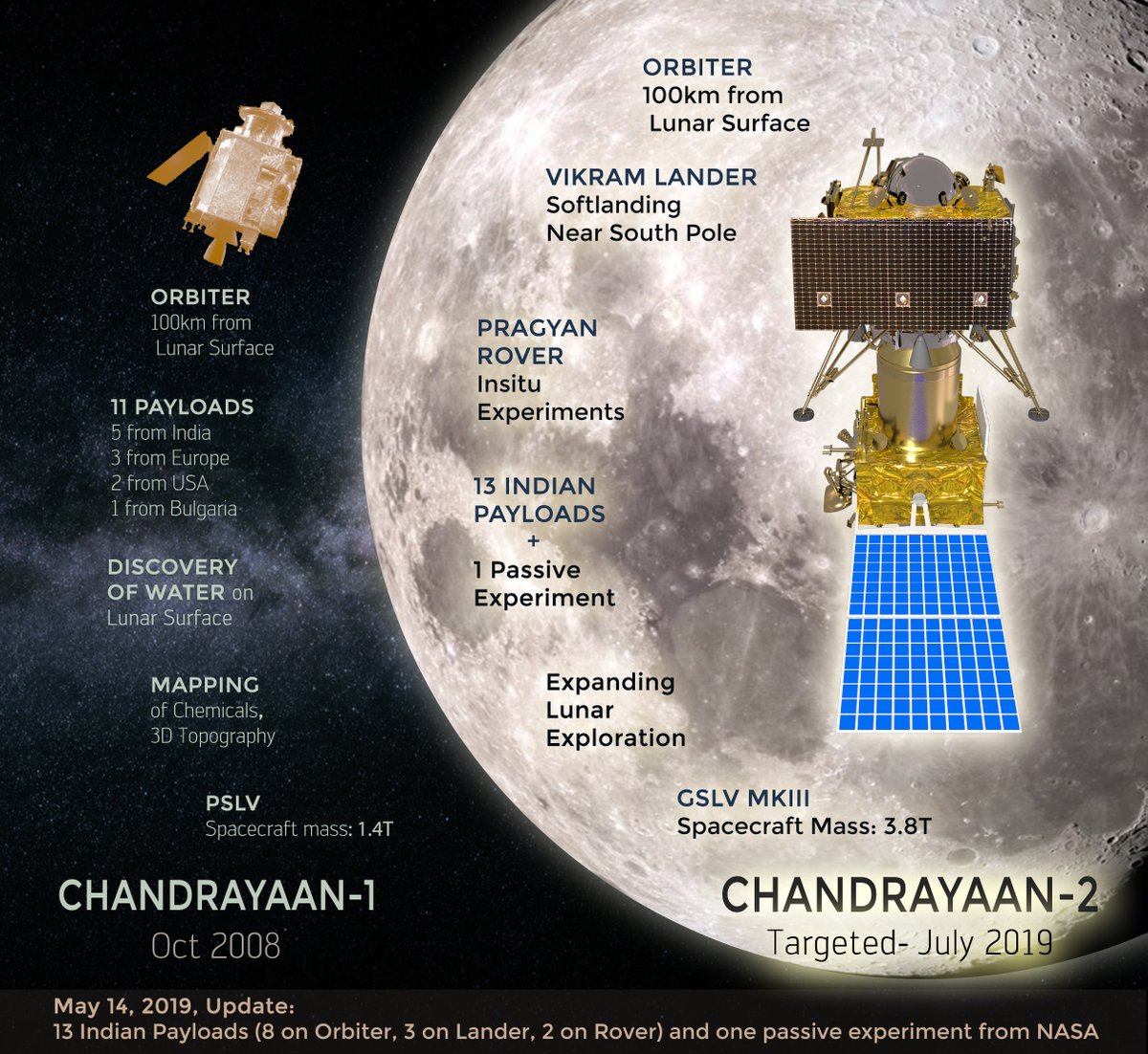

Chandrayaan-2 was India's second mission to the moon, and was a follow-up mission from the Chandrayaan-1 mission that assisted in confirming the presence of water/hydroxyl on the moon in 2009.

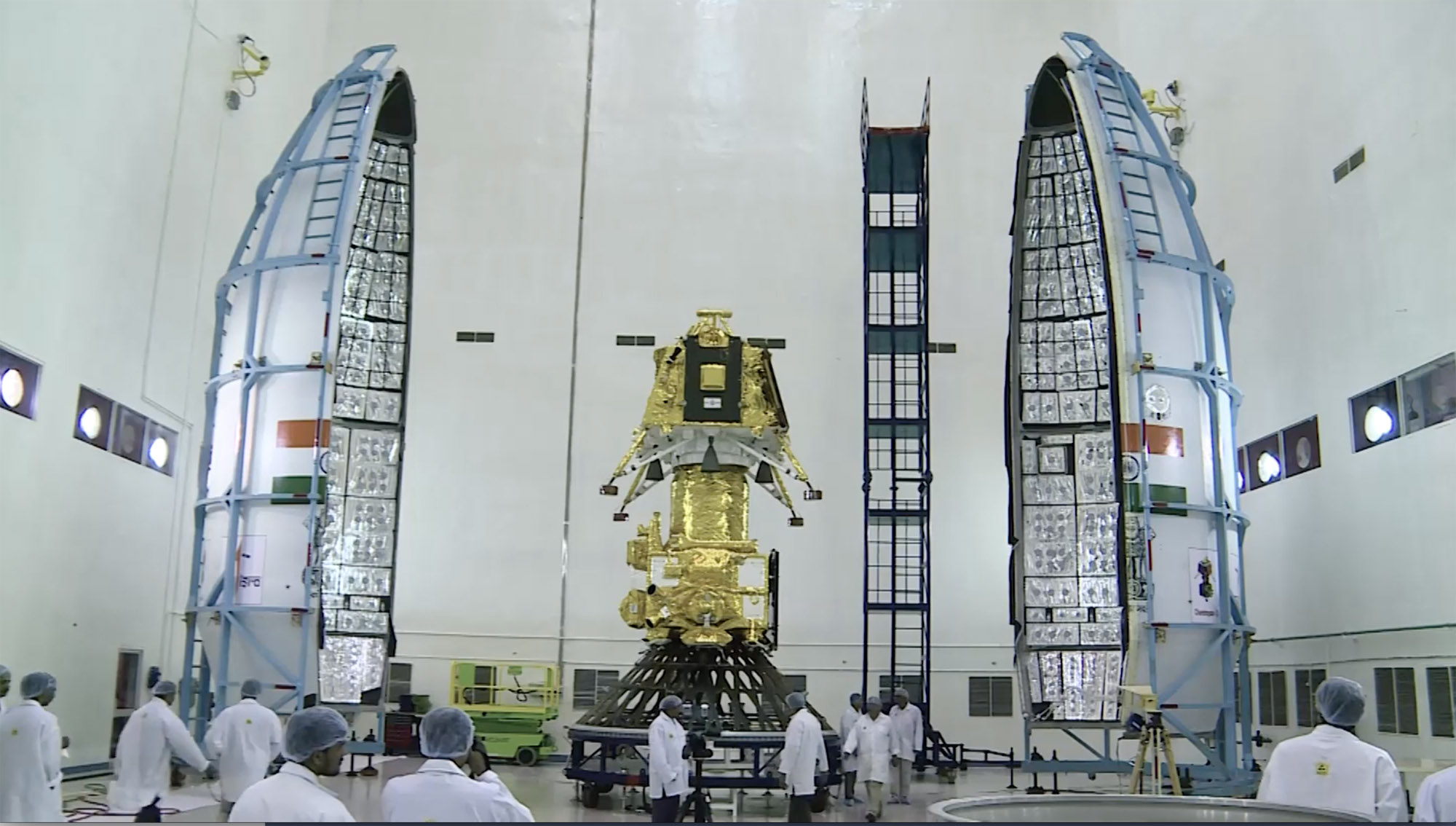

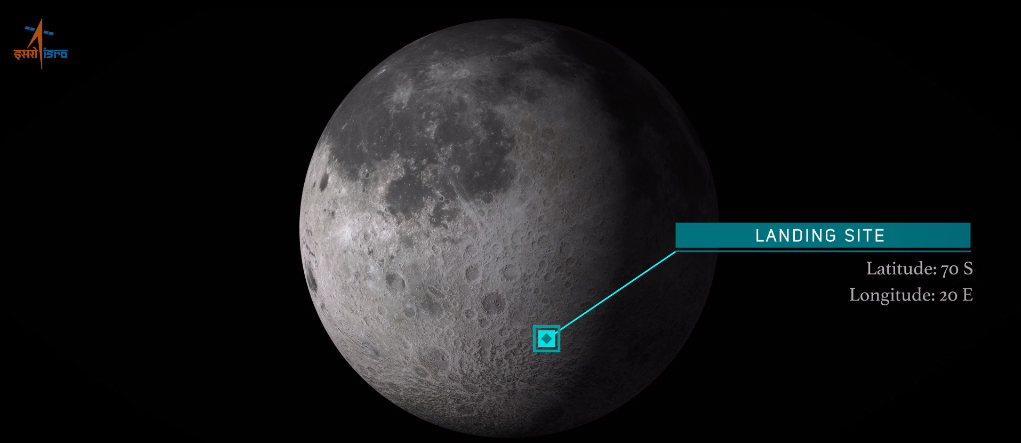

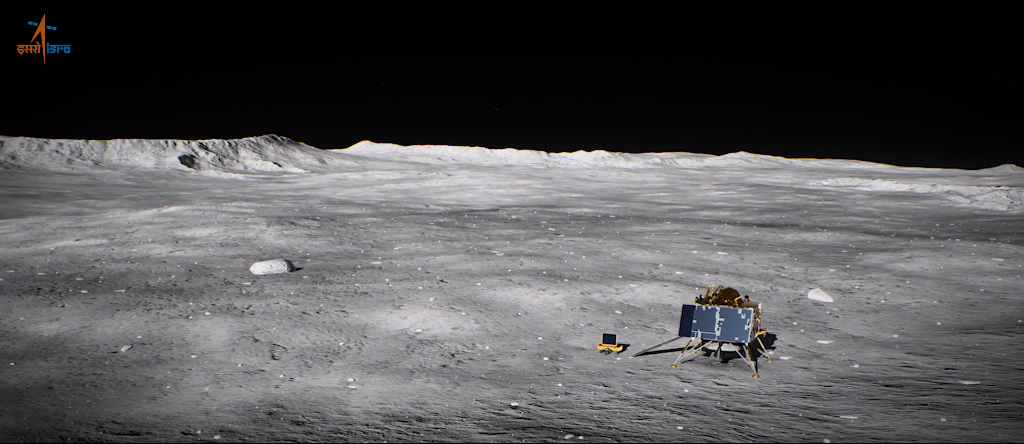

Chandrayaan-2 launched from the Satish Dhawan Space Center in Sriharikota, India, aboard a Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV) rocket on July 22, 2019 and reached lunar orbit on Aug. 19. During the Sept. 6 (Sept. 7 IST) moon landing attempt, ISRO officials lost contact with the Vikram moon lander as the probe was just 1.3 miles (2.1 kilometers) above the lunar surface. Officials have been unable to reach the lander since losing contact on Sept. 6.

Despite the apparent crash-landing of the lander, ISRO has confirmed that all the instruments on board the orbiter are working well. The current orbiter carries eight different instruments — and Indian scientists are already poring over some of the mission's very first science data. On Oct. 4, ISRO released photos the orbiter's High Resolution Camera took on Sept. 5 of a crater called Boguslawsky E, located near the lunar south pole.

Related: India's Space Program: Complete Coverage

Development and science

Initially, ISRO planned to partner with Russia to perform Chandrayaan-2. The two agencies signed an agreement in 2007 to launch the orbiter and lander in 2013. Russia later pulled out of the agreement, however, according to a news report from The Hindu. The Russian lander's construction was delayed after the December 2011 failure of Roscosmos' Phobos-Grunt mission to the Martian moon of Phobos, the report stated.

Russia subsequently pulled out of Chandrayaan-2 altogether, citing financial issues. Some reports stated that NASA and the European Space Agency were interested in participating, but ISRO proceeded with the mission on its own.

The goal of the Chandrayaan-2 orbiter was to circle the moon and provide information about its surface, ISRO stated previously. "The payloads will collect scientific information on lunar topography, mineralogy, elemental abundance, lunar exosphere and signatures of hydroxyl and water-ice," ISRO said on its website. The mission was also supposed to send a small, 20-kilogram (44 lbs.), six-wheeled rover to the surface that could move semi-autonomously, examining the lunar regolith's composition.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This is the list of instruments that were on the orbiter, according to the Planetary Society:

- Terrain Mapping Camera 2 (TMC-2), which will map the lunar surface in three dimensions using two on-board cameras. A predecessor instrument called TMC flew on Chandrayaan-1.

- Collimated Large Array Soft X-ray Spectrometer (CLASS), which will map the abundance of minerals on the surface. A predecessor instrument called CIXS (sometimes written as C1XS) flew on Chandrayaan-1.

- Solar X-ray Monitor (XSM), which looks at emissions of solar X-rays.

- Chandra's Atmospheric Composition Explorer (ChACE-2), which is a neutral mass spectrometer. A predecessor instrument called CHACE flew on Chandrayaan-1's Moon Impact Probe.

- Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), which will map the surface in radio waves. Some of its design is based on Chandrayaan-1's MiniSAR.

- Imaging Infra-Red Spectrometer (IIRS), which will measure the abundance of water/hydroxl on the surface.

- Orbiter High Resolution Camera (OHRC) to examine the surface, particularly the landing site of the lander and rover.

The lander's instruments included:

- Instrument for Lunar Seismic Activity (ILSA), to look for moonquakes.

- Chandra's Surface Thermophysical Experiment (ChaSTE), to examine the surface's thermal properties.

- Radio Anatomy of Moon Bound Hypersensitive ionosphere and Atmosphere (RAMBHA-Langmuir Probe), to look at plasma density on the surface.

The rover also carried two science instruments designed to look at the composition of the moon's surface: the Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscope (LIBS) and the Alpha Particle X-Ray Spectrometer (APXS).

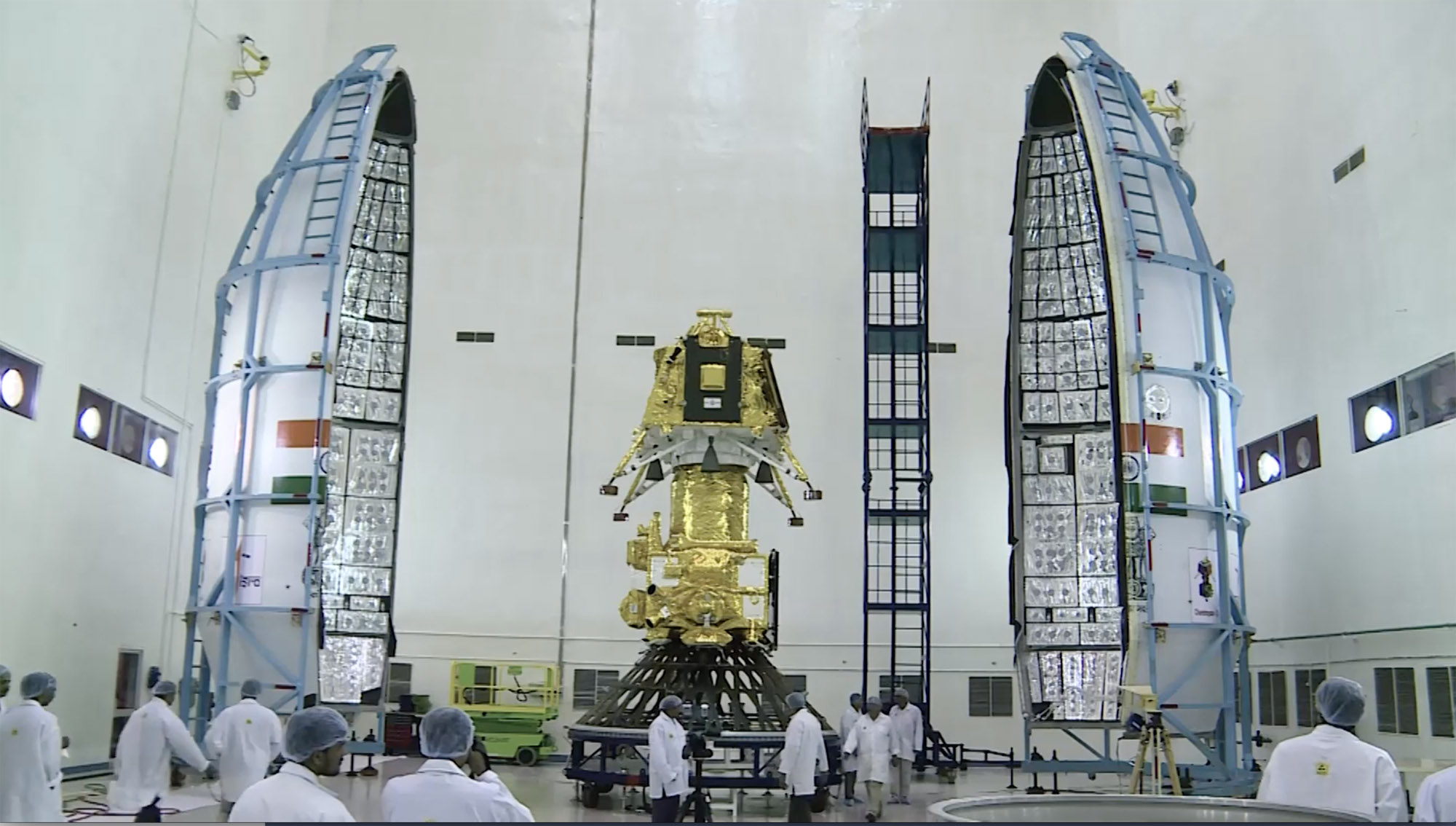

Landing near the pole

Chandrayaan-2's lander and rover were targeted for a location about 600 km (375 miles) from the south pole, which would have been the first time any mission touched down so far from the equator, according to a January 2018 article in Science magazine. ISRO planned to use the experience for more challenging missions in the future, such as touching down on an asteroid or Mars, or sending a spacecraft to Venus, IRSO chair Kailasavadivoo Sivan said in the article.

The lander was expected to last about one lunar day, or 14 Earth-days, and it was unclear if it would revive after falling into the darkness of a lunar night and ISRO will have to wait until another mission to find out.

On Sept. 6, 2019 at 4:48 p.m. EDT (2048 GMT) K. Sivan, the director of ISRO, confirmed that communication had been lost with the Chandrayaan-2 Vikram lander.

"Vikram lander descent was as planned and normal performance was observed up to an altitude of 2.1 kilometers [1.3 miles]," Sivan said in an announcement at mission control. "Subsequently the communications from the lander to the ground station was lost. The data is being analyzed."

Video: The Moment India Lost Contact with the Vikram Moon Lander

Related: India's Chandrayaan-2 Mission to the Moon in Photos

Sivan did not specify when ISRO would be able to provide updates about the fate of the Vikram lander. According to data shown during the descent maneuver, the lowest altitude reported back to Earth was 0.2 miles (0.33 km) above the lunar surface.

A plot comparing live data received to the mission's trajectory suggested that Vikram was about 0.6 miles (1 km) horizontally off-track from the targeted landing site when communications stopped.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi had arrived onsite at the ISRO Telemetry, Tracking and Command Network (ISTRAC) in Bengaluru, India, about half an hour before scheduled touchdown of Vikram and was there to witness the communication loss.

"India is proud of our scientists!" Modi wrote in a Twitter update shortly after learning of the anomaly. "They've given their best and have always made India proud. These are moments to be courageous, and courageous we will be!"

"We remain hopeful and will continue working hard on our space programme," he added.

Additional resources:

- Read more about the Chandrayaan-2 mission from the Indian Space Research Organisation.

- Amazing Moon Photos from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

- Learn more about Chandrayaan-2 and it's two land rovers from NASA's Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute

This article was updated on Oct. 8, 2019 by Space.com Reference Editor Kimberly Hickok.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.