What does space do to the human body? 29 studies investigate the effects of exploration

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronauts endure radiation, weightlessness, isolation and a number of other physical and mental stresses of spaceflight. So what do these hazards actually do to their bodies?

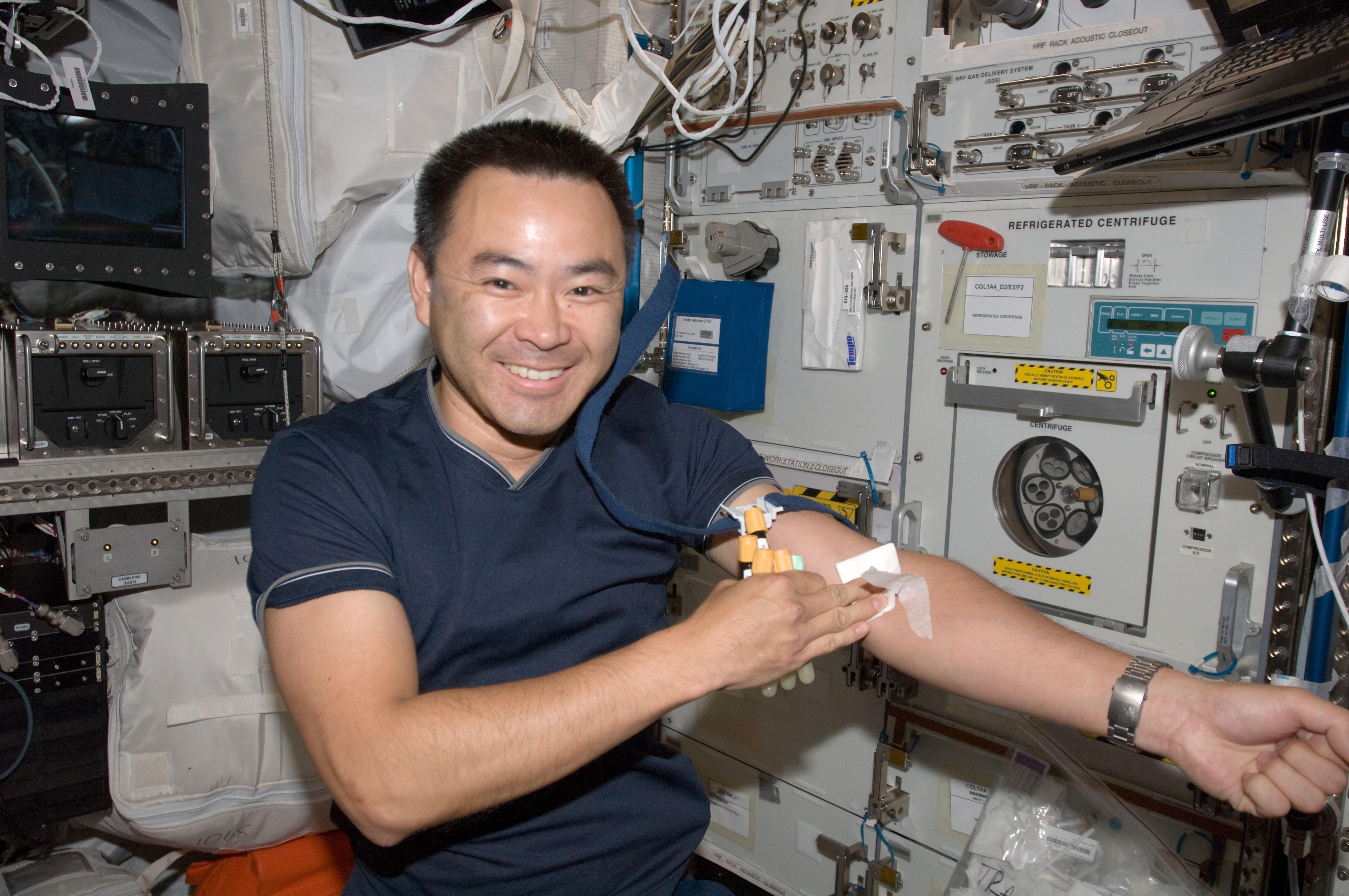

A collection of 29 papers,19 of which were published Nov. 25, has advanced our knowledge of how spaceflight affects the human body farther than ever before. This work stems from the NASA "Twins Study," which followed NASA astronaut Scott Kelly's year-long mission in space on board the International Space Station while his twin brother Mark Kelly, a retired NASA astronaut, served as a control back on Earth.

While the Twins Study was groundbreaking, it only really looked at these two astronauts. With this new package of papers, scientists have observed the effects of spaceflight in 56 astronauts who've visited the space station.

Article continues below"These manuscripts span >200 investigators from dozens of academic, government, aerospace, and industry groups, representing the largest set of astronaut data and space biology data ever produced, including longitudinal multi-omic profiling, single-cell immune and epitope mapping, novel radiation countermeasures, and detailed biochemical profiles of 56 astronauts," a paper summarizing this collection states.

Related: By the numbers: astronaut Scott Kelly's year-in-space mission

With such an incredible body of data to work with and such a large, international collaboration, scientists were able to not just validate what they found in the Twins Study, but expand the study of how space affects the human body to new levels.

"It's a wide range of different studies," Colorado State University Professor Susan Bailey, who was a principal investigator of the NASA Twins Study and a senior investigator for many of these papers, told Space.com. "It's really building a great foundation for 'what do we know about the effects of long duration spaceflight on the human body?' And 'what do we need to be looking for and concerned about as we go forward?'" Bailey added that this will be increasingly important as humans venture out to the moon and farther from Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While each of the 29 papers tackles a unique factor of the effects of spaceflight on humans, there are a handful of major findings that both validate what was found in the Twins Study and further scientists' understanding of these health effects.

Six features

When it comes to studying the health effects of spaceflight, researchers have identified six key factors that determine what happens to a person's body in space.

"We're proposing that there are really six consistent features that we see again and again in mice and rodents and human subjects and cell lines. And that really points toward — what are some of the core factors that mediate how the body responds to being in space?" Chris Mason, an associate professor of physiology and biophysics at Weill Cornell Medicine who was also a principal investigator of the Twins Study and a senior or co-senior investigator for many of these papers, told Space.com.

These six features include mitochondrial dysregulation, oxidative stress, free radicals, DNA damage, telomere length, variations in microbiomes and epigenetic changes. The first, mitochondrial dysregulation, refers to how mitochondria (an organelle that generates most of the chemical energy in a cell, or the "powerhouse of the cell") function differently, which could lead to health issues. Scientists also detected oxidative stress, an imbalance of free radicals and antioxidants in the body, which Bailey thinks is likely caused by the radiation astronauts experience while in space, she said. Along those lines, the authors of these papers also studied free radicals, or unstable atoms in the human body that could damage cells and lead to illnesses like cancer in astronauts during spaceflight.

Additionally, the researchers saw evidence of DNA damage, which is expected with the type of radiation exposure that astronauts endure. These papers also showed that astronauts in flight have elongated telomeres — protective structures at the ends of chromosomes — which shrink again upon landing on Earth. This was interesting because researchers with the Twins Study were surprised to see Kelly's telomeres lengthen in space and shorten back on Earth, but with this work they've shown that Kelly wasn't an outlier and this happened across the board with the astronauts they studied.

The papers also showed a variety of microbiomes — the collection of genetic material from all microbes in and on a human body — with the astronauts, which is to be expected because they are all unique Earthlings. Researchers studied not just the variety of astronaut microbiomes but how each person's microbes were altered with spaceflight and the environment inside the space station. Lastly, the new research showed evidence of epigenetic changes, or changes to the physical structure of DNA, where astronauts are experiencing "gene regulation change," or the process of turning genes "on" and "off" as cells react to different environments, Mason said.

Like the findings which continued to show how telomeres lengthen during spaceflight, these papers validated many of the effects which researchers saw in Scott Kelly during the Twins Study. But, with so much more data pulled from a larger pool of both astronauts and other models like rodents, researchers have a better picture of the effects of human spaceflight and have been able to validate what was found with Kelly.

Interestingly, in some of these papers, researchers validated these findings not with more astronauts, but by looking at Mount Everest climbers. They found that these climbers have longer telomeres while they're climbing, although the reason for the change in length is not yet fully understood.

Related: From radiation to isolation: 5 big risks for mars astronauts (videos)

Space treatments

By validating prior studies on the health effects of spaceflight and expanding our understanding of these extreme circumstances on the human body, scientists can start to consider and develop potential preventative measures, treatments and therapies so that future astronauts who spend even more time in space — whether they're living in a settlement on the moon or traveling even farther away to Mars — can also be more prepared for what to expect.

While engineers and scientists are currently working on ways to decrease the amount of dangerous radiation astronauts are exposed to — which scientists think is a huge factor in many of the negative health effects of spaceflight — they are also considering what existing medications could be effective in mitigating these effects, Mason explained.

But, primarily, this work creates a much greater and more concrete understanding of these effects. For example, telomere elongation can lead to increased chromosome activation and an increased risk of cancer, Bailey explained. On the other side, those few astronauts who might show shorter than expected telomeres could actually be at risk for cardiovascular disease, she said.

While thinking about how detecting or even treating such serious health conditions from Earth in astronauts on the space station, the moon or even Mars is a daunting task, these are things that we will need to consider if astronauts are going to be spending significantly longer periods of time in space.

Next steps

To more fully understand why things like telomere elongation happen during spaceflight, researchers will continue to study the phenomena as time goes on. In fact, "we are hoping to get as many as 31 astronauts over the next 10 years to do very similar studies," Bailey said.

And as the astronaut corps gets continually more diverse, especially with the boom in commercial spaceflight, that will only further diversify their data and help to make their findings as well-rounded and helpful as possible when considering the health of future astronauts, she added.

Of the 29 new papers, 19 were published Nov. 25 across five Cell Press journals (including Cell, Cell Reports, iScience, Cell Systems and Patterns.) The 10 other papers included in this package are either in review or online as pre-prints or early access articles.

Email Chelsea Gohd at cgohd@space.com or follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Chelsea “Foxanne” Gohd joined Space.com in 2018 and is now a Senior Writer, writing about everything from climate change to planetary science and human spaceflight in both articles and on-camera in videos. With a degree in Public Health and biological sciences, Chelsea has written and worked for institutions including the American Museum of Natural History, Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine and Live Science. When not writing, editing or filming something space-y, Chelsea "Foxanne" Gohd is writing music and performing as Foxanne, even launching a song to space in 2021 with Inspiration4. You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd and @foxannemusic.