Massive 'forbidden planet' orbits a strangely tiny star only 4 times its size

The discovery could challenge our theories of how gas giants like Jupiter form.

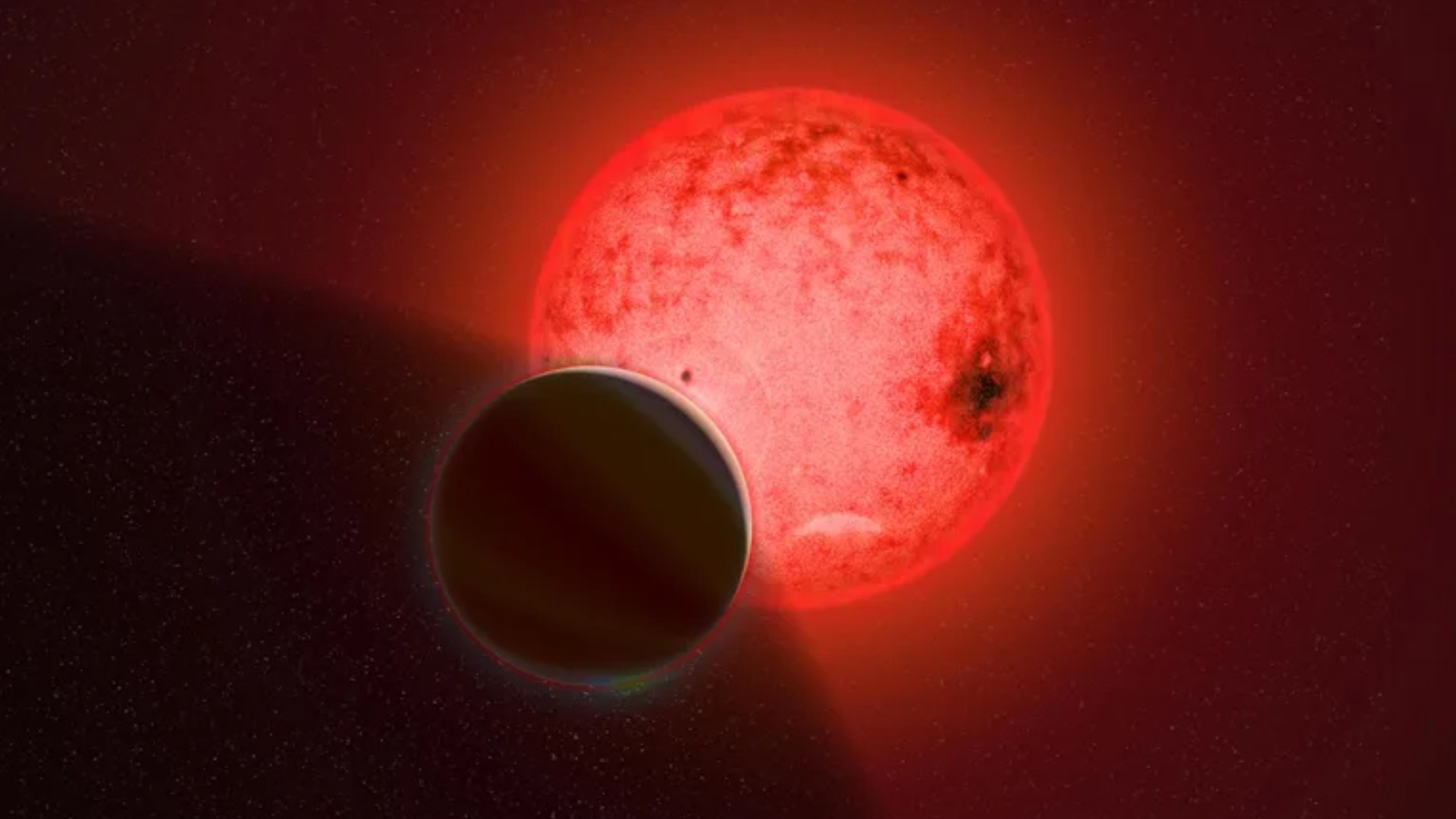

Astronomers have discovered an unusual planetary system consisting of a Jupiter-sized planet orbiting a tiny star that is only four times the size of the solar system gas giant. This "forbidden" configuration of a massive planet orbiting a relatively tiny star could challenge theories of how gas giant planets form.

The extrasolar planet, or "exoplanet," orbits a red dwarf star designated TOI 5205 that is much cooler and smaller than the sun. The small size and relatively cool temperatures of these M-dwarf stars, the most common type of stellar body in the Milky Way, make them redder than the sun.

Though on average this class of stars hosts more planets around them than other star types, it was previously believed that their formation makes them unlikely to be orbited by gas giants. The discovery of this exoplanet — designated TOI 5205b — by astronomers using NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) telescope challenges that concept. The planet was confirmed and characterized by the team using various ground-based telescopes and instruments.

Related: Exoplanets: Worlds Beyond Our Solar System

"The host star, TOI-5205, is just about four times the size of Jupiter, yet it has somehow managed to form a Jupiter-sized planet, which is quite surprising!" team leader and Carnegie Science astronomer Shubham Kanodia said in a statement.

Though gas giants have been discovered around M dwarf stars before, none of them have been discovered orbiting such a low mass example of this class of star-like TOI-5205.

Planets are created in spinning discs of gas and dust called "protoplanetary discs" that surround young stars. This material is the remains of the same matter that collapsed to birth its central star. When dense patches collapse under their own gravity planet cores are born and they then collect more material.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Current planet formation models suggest that to birth a gas giant it takes material equivalent to 10 times the mass of Earth. This first forms a rocky core and this core goes on to accumulate gas to form the disc to grow a giant planet. This process has to occur quickly, however.

"In the beginning, if there isn't enough rocky material in the disk to form the initial core, then one cannot form a gas giant planet. And at the end, if the disk evaporates away before the massive core is formed, then one cannot form a gas giant planet. And yet TOI-5205b formed despite these guardrails," Kanodia explained in the statement. "Based on our nominal current understanding of planet formation, TOI-5205b should not exist; it is a 'forbidden' planet."

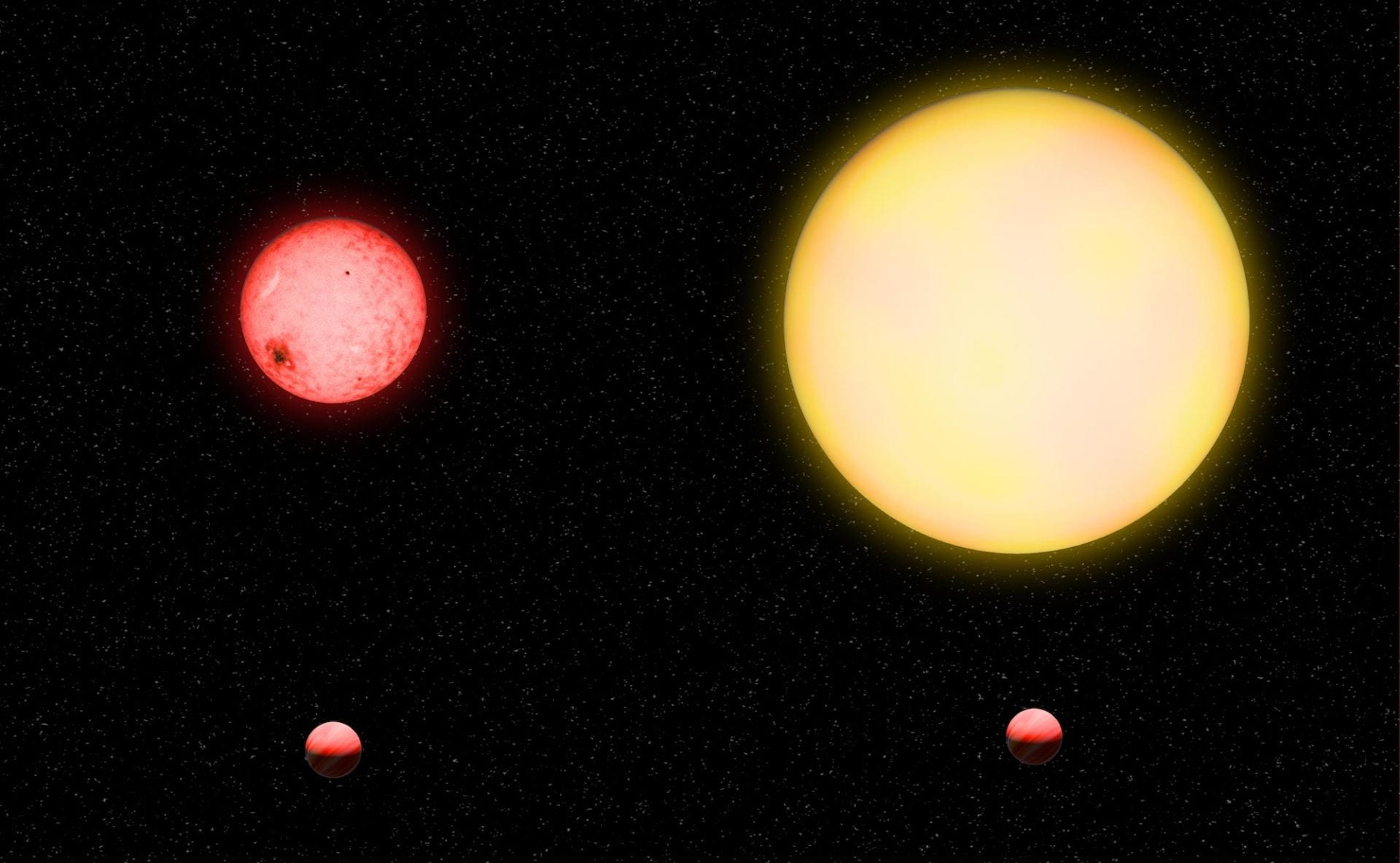

To picture how unbalanced this system is to planetary systems that astronomers expect, imagine our star the sun squashed down to the size of a grapefruit. That size reduction would mean the largest gas giant in our solar system, Jupiter, would be about the size of a garden pea.

The TOI-5205 system is more like a pea orbiting a lemon.

The size disparity in the size is so great that when TESS used the drop in light caused by a planet as it passes in front of its star, known as the transit method, that dip in light was 7% of the star's total light output.

That makes the dimming of TOI-5205 by this Jupiter-sized exoplanet the largest known drop in light caused by an exoplanet transit.

This extreme dip in light or technically, "large transit depth," could make the system ideal for follow-up investigations with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

Observations with the JWST could help determine the composition of TOI-5205 b's atmosphere and may shed light on the processes that birthed this "forbidden" planet.

The team's research is published in The Astronomical Journal.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.