The hunt is on for exomoons around alien planets and scientists may have just found one

The find, the second candidate for an exomoon, may be the next big thing in astronomy.

It's time for another tantalizing glimpse of what alien solar systems might look like.

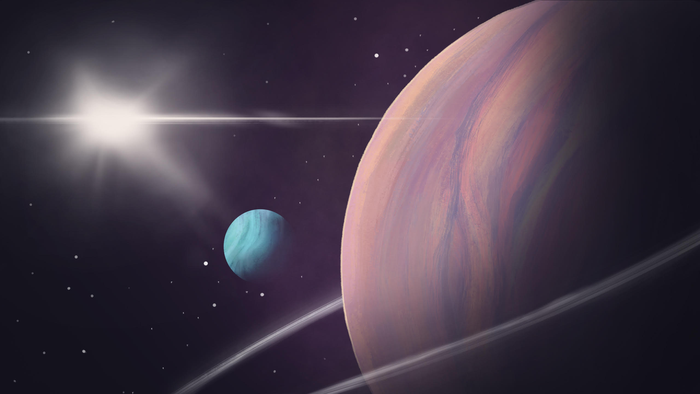

Astronomers have announced the possible detection of an exomoon, or a moon in another stellar system from our own, the second such candidate observation to date. The signal comes from a star studied by NASA's now-retired Kepler space telescope, and scientists behind the new research say that their analysis points to a mini-Neptune moon orbiting a planet about the size of Jupiter. If the strange signal does turn out to represent an exomoon, the discovery would give scientists a new understanding of not just this stellar system, but of how such systems work across the galaxy more generally.

"These are objects that everybody suspected would be there, but there wasn't a lot of formal research on it before 2007," Marialis Rosario-Franco, an astrophysicist at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in New Mexico who studies exomoons but was not involved in the new research, told Space.com.

Related: The 10 biggest exoplanet discoveries of 2021

"Exolunar science, it's still quite a young field that is brimming with possibilities," she added. "This is something that we are just starting to conceive that we might be able to observe — and we are not directly observing these objects; we are simply observing the perturbation that the presence of those objects have in an otherwise normal exoplanet signal."

The scientists behind the new research focused on data gathered by the Kepler spacecraft before its demise in 2018. The instrument specialized in staring at stars, watching for tiny changes in brightness, since a small rhythmic dimming could represent a planet crossing between its star and the telescope. Astronomers have found some 2,700 confirmed planets in Kepler's data, plus another 2,000 signals that may represent alien worlds, according to NASA tallies.

In the new research, scientists looked at 70 of those data sets, each representing what astronomers believe could mark a cool gas giant like the massive planets of our own neighborhood. The researchers then ran a battery of models to see which Kepler observations might match what they would expect to see if such a planet had a moon. Only three stars made the cut.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The scientists then ran through other scenarios that could create the same data. For one system, the team realized the signal could have been caused by the Kepler spacecraft itself; for another, the signal could come from dark spots moving over the surface of the star. But for the last candidate, a star known as Kepler 1708, none of their alternative explanations worked.

"It's a stubborn signal," David Kipping, an astronomer at Columbia University and lead author of the new research, said in a statement. "We threw the kitchen sink at this thing, but it just won't go away."

Kipping and other authors on the new research also spotted the first exomoon candidate, in a system dubbed Kepler 1625. The new paper relies on a similar technique, but it's even more conservative than the already-rigorous process followed in the first study, according to Rosario-Franco. She called the Kepler 1625 moon "quite generally accepted by the astrophysical community," albeit still unconfirmed.

That acceptance is due in part to additional observations by the Hubble Space Telescope, and scientists expect that the new exomoon candidate will spur more observations as well.

"I’m not convinced by this candidate yet, but it's definitely worth taking another look to try to confirm," Laura Kreidberg, an exoplanet scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany who was not involved in the new research, told Space.com in an email.

And of course, the next major observatory, NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, is finally in space with science work scheduled to start this summer.

"I would be convinced if we observed another transit of the planet with JWST and saw an additional dip in the brightness due to the moon," Kreidberg wrote. "Exomoons push the limits of our detection capability, so it’s worth being really careful."

Both candidate exomoons are larger than any moon in our own solar system, but that's not surprising, Kipping said. "The first detections in any survey will generally be the weirdos," he said. "The big ones that are simply easiest to detect with our limited sensitivity."

A feast of planets and dreams of moons

Scientists spotted the first-ever exoplanets just 30 years ago; since then, the field has exploded, convincing scientists that a standalone star is likely rarer than a star with at least one planet.

So if planets are common, what next? Our own solar system has more than 200 moons, making this category the next logical target — albeit a tricky one given these objects' small size. "Astronomers have found more than 10,000 exoplanet candidates so far, but exomoons are far more challenging," Kipping said.

That difficulty means every possible discovery really counts. "It's very exciting to have another candidate," Rosario-Franco said. And she said it's particularly intriguing that both moons are so large — the size of planets themselves.

Based on our solar system, scientists have three theories about how moons come to be: the remains of a giant impact, a passing rock captured by a planet or coalescing out of a debris disk like a planet. But none of the three ideas could explain these candidates, a new puzzle Rosario-Franco said she's pleased to see scientists tackle.

"Exomoons have great potential to teach us about how planets form in general," Kreidberg said. "They’re also really cool! There are dozens of moons in our own solar system, so I wouldn’t be surprised if they’re common around other stars too.

At a smaller scale, an exomoon detection would also offer scientists a more detailed portrait of a planetary system.

"I think it's key to have as much information from the surroundings of that stellar system as possible and from the surroundings of a specific exoplanet as possible," Rosario-Franco said. "Small objects can provide big insight into the dynamics, the orbital evolution and migration of all these planets, moons, satellites [and] asteroids that are a part of basic stellar systems that we are just starting to understand."

The new research is described in a paper published Thursday (Jan. 13) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.