Presidential Historian Douglas Brinkley Talks JFK, Moonshots and Apollo 11

The Space Age in the United States "was born in the crucible of World War II," Douglas Brinkley said.

NEW YORK — Presidential historian Douglas Brinkley addressed a crowd seated beneath the space shuttle Enterprise at the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum here to discuss his latest book, "American Moonshot: John F. Kennedy and the Great Space Race" (Harper, 2019). The Rice University professor offered a fascinating look at the journey to put the first human on the moon and the people who made that feat possible, particularly President John F. Kennedy and rocket engineer Wernher von Braun.

Born in 1917, Kennedy was part of "the first generation born in the age of flight, [the] age of aviation," Brinkley said. The Wright brothers were "barely getting a plane up" in 1903, and Kennedy would have been just 10 years old when Charles Lindbergh flew the Spirit of St. Louis across the Atlantic Ocean.

Brinkley said the smartest, as well as perhaps the most controversial, of that generation of rocket engineers was von Braun, who would go on to develop the Saturn V rocket that carried Apollo astronauts to the moon 50 years ago this summer.

Related: Reading Apollo 11: The Best New Books About the US Moon Landings

The Space Age in the United States "was born in the crucible of World War II," Brinkley said. Kennedy and von Braun were both participants in that war, albeit on opposite sides of the planet and in opposing armies. But within two decades of the war's end, their relationship served to bolster the NASA space program.

Von Braun began his career in Germany, eventually rising to become Nazi Germany's leading missile scientist. According to Brinkley, von Braun could have been charged for war crimes for what he did in that role.

"Beyond being a Nazi, beyond trying to destroy London [with V-2 rocket weaponry] … he used slave labor at the Dora [concentration] camp, a subcamp at Buchenwald," Brinkley said. "If the British army captured von Braun after what he tried to do to London, he very well may have been tried there [in the United Kingdom]."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The engineer was smart enough to realize that and decide to do something about it, Brinkley said. "But von Braun was really an opportunist whose real dream was the moon, and he realized he didn't want to get captured by Stalin's Red Army, he didn't want to get captured by the British," Brinkley said. "So the only card he had — and it was a big one — was to hide all of his technology for rockets and missiles into a cavern, blow up the entrance, sneak out of the military base … with 137 of the top Nazi rocket engineers, rocket scientists, and surrender to the U.S. Army."

In an agreement known as Operation Paperclip, these rocket scientists became "prisoners of peace" and developed and tested rockets for the U.S. Army in Texas.

JFK and von Braun met in 1953, according to Brinkley. Kennedy had just become a U.S. senator, and von Braun had garnered positive publicity by partnering with Walt Disney for a television program about space exploration and the world of tomorrow.

But the Soviet Union had also recruited German weapons experts after World War II, and in 1957, that country successfully launched the first intercontinental ballistic missile. Several months later, the USSR launched the first artificial satellite into space: Sputnik.

President Dwight Eisenhower created NASA a year later, for the peaceful exploration of space, and Kennedy supported the agency when he began his presidency in 1961. But when the Soviets launched the first mission to send a human, Yuri Gagarin, into space, Kennedy became eager to advance the status of the United States in the space race.

Related: Apollo 11 at 50: A Complete Guide to the Historic Moon Landing Mission

"During Kennedy's presidency, we have six Mercury missions," said Brinkley. "All are successful, all with big ratings. All made big heroes … and Kennedy keeps the NASA budget going."

Brinkley credited Kennedy's successful campaign for the moon mission to his fiercely competitive nature and his talent at public speaking. Kennedy's rhetoric about the program ranged from his famous "moon speech," delivered weeks after Gagarin reached space, to the president's public pleas to fund the program.

"The day before he was killed, he was in San Antonio and he talked about how space medicine was changing public health," said Brinkley, "how we had created kidney dialysis machines, heart defibrillators, CAT Scans, MRIs; that biomed miracles were happening because of the funding for Apollo. Kennedy was constantly talking about the spinoff technology."

That continued until, of course, his assassination in 1963. After JFK's burial in Arlington National Cemetery, his widow, Jacqueline Kennedy, asked the new president, Lyndon Johnson, to keep her husband's moonshot dream alive, Brinkley said.

In the midst of the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement and the cultural changes of the 1960s, the Apollo program managed to retain funding. Opinion shifted when the Apollo 1 astronauts died in a training accident, but the program still had momentum.

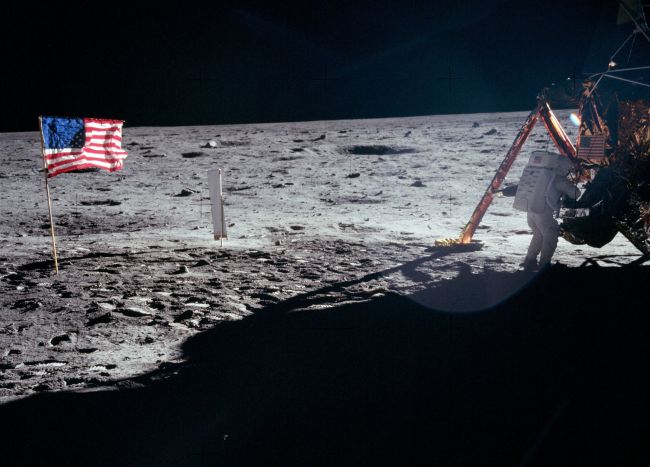

And then, in the final year of the decade, Kennedy's legacy came to fruition as Apollo 11 reached the moon on a Saturn V rocket developed by von Braun.

This year, NASA will celebrate the 50th anniversary of the 1969 accomplishment, but the mission's success was not a sure thing. President Richard Nixon, in office at the time, had his speech writer draft a somber speech in case the mission failed, and when Brinkley interviewed Neil Armstrong in the early 2000s, the Apollo astronaut said the mission had a 50-50 chance of failing or succeeding.

Brinkley ended the presentation by emphasizing the innovations made possible by the Apollo program and how "we may be living in what future generations think of as the Age of Armstrong."

But Brinkley doesn't want history to be remembered just by its successes.

"NASA was lucky to have a rocket engineer as talented as von Braun to work on Apollo, but he shouldn't be remembered as an American hero," Brinkley said during a March 2019 C-SPAN interview. "His direct role on the Nazi concentration-camp labor programs, where thousands perished under inhumane conditions, makes him a pariah figure of sorts … he would claim that he had no choice. It was the German homeland, but many rocketeers left Germany or at least a few did of the key ones" so they wouldn't have to serve the Nazis.

Brinkley said he wanted to make clear in the book that both chapters in von Braun's life are worth discussing. "He was the essential man to get us to the moon, but we want to put him into a proper historical perspective and not glorify him."

- NASA's Historic Apollo 11 Moon Landing in Pictures

- 'Chasing the Moon' Shows Nazi Past of Engineer Wernher Von Braun in Early Space Program (Video)

- Catch These Events Celebrating Apollo 11 Moon Landing's 50th Anniversary

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.