Does the sun rotate?

As a ball of ultra-hot gas, how does the sun rotate? This complex form of rotation drives some fascinating phenomena.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The sun's permanent position in the sky, plus the fact that Earth and the other planets revolve around it, may give the impression that it is static and does not move or rotate.

Yet we have been aware that the sun rotates since the 17th century. Like the majority of the solar system's planets, this rotation is counter-clockwise, but as well as being significantly slower than Earth's rotation, the sun's rotation is much more complex.

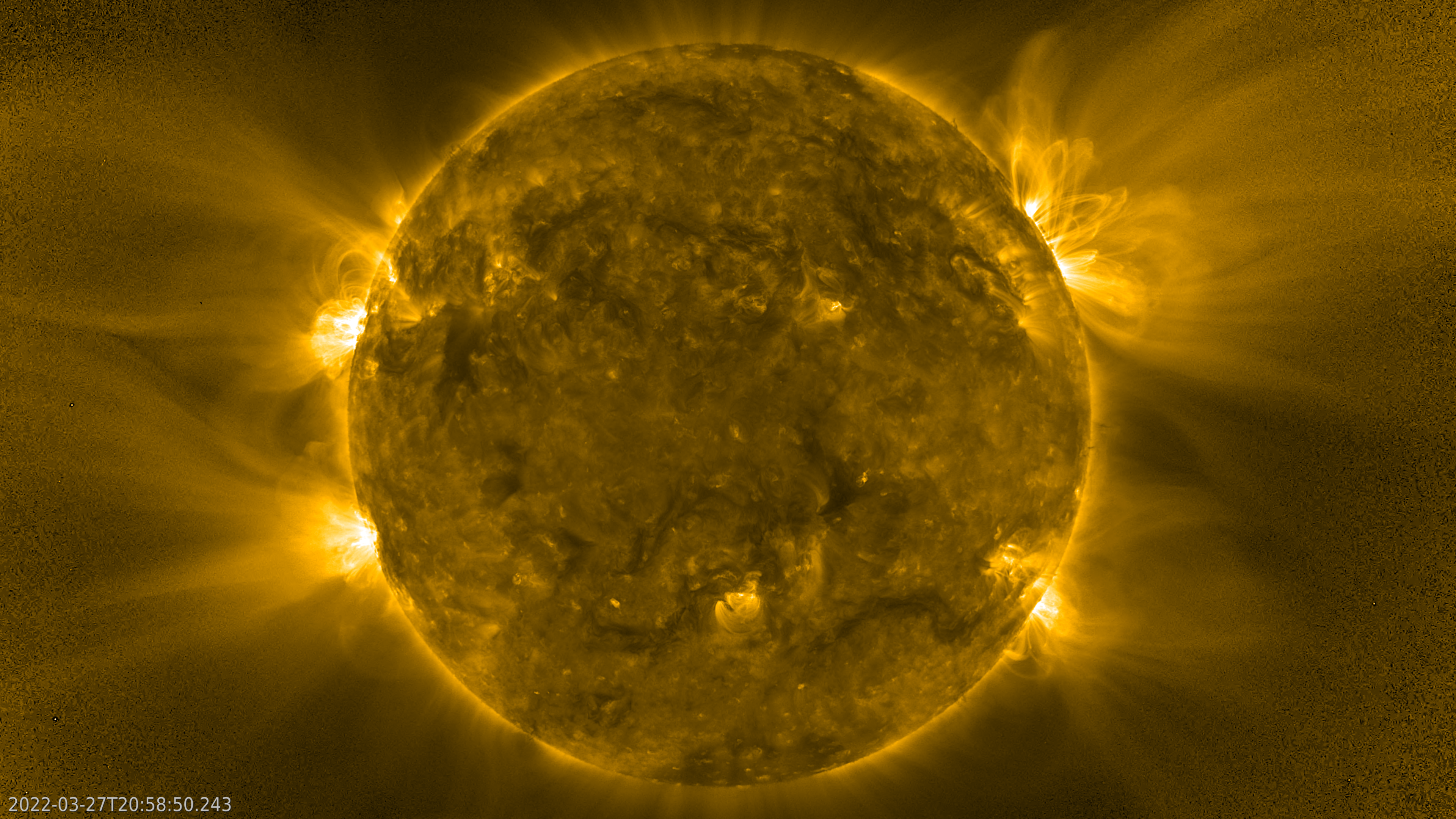

How we know the sun rotates

The discovery that the sun rotates dates back to the time of Galileo Galilei, according to The British Library. Along with several of his contemporary earlier astronomers, Galileo had observed dark spots of the sun that we now call sunspots and understand to be important parts of the solar cycle.

Article continues belowGalileo noticed something else too. He found these dark spots appeared to move, vanishing and returning as he observed the sun with his telescope.

In 1612, the early scientist wrote: "It is also manifest that their rotation is about the sun… to me, it seems more probable that the movement is of the solar globe than of its surroundings," according to the book 'Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo' (Doubleday, 1957).

By using sunspots, he had discovered that the sun rotates, pleasingly ironic given these dark cool patches on the surface of the sun are an artifact of that rotation.

To this day, astronomers and solar scientists use sunspots and other features on the surface of our star to measure its rotation. Yet, there is more to learn about the sun's rotation. Primarily, how different it is from the rotation of our planet.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Is the sun's rotation different?

While Earth and the other inner planets are composed of solid rock, the sun is an ultra-hot ball of dense ionized gas — mainly hydrogen and helium — called plasma.

That means that the way it rotates is different than the way our planet, Mars, Venus, and Mercury do.

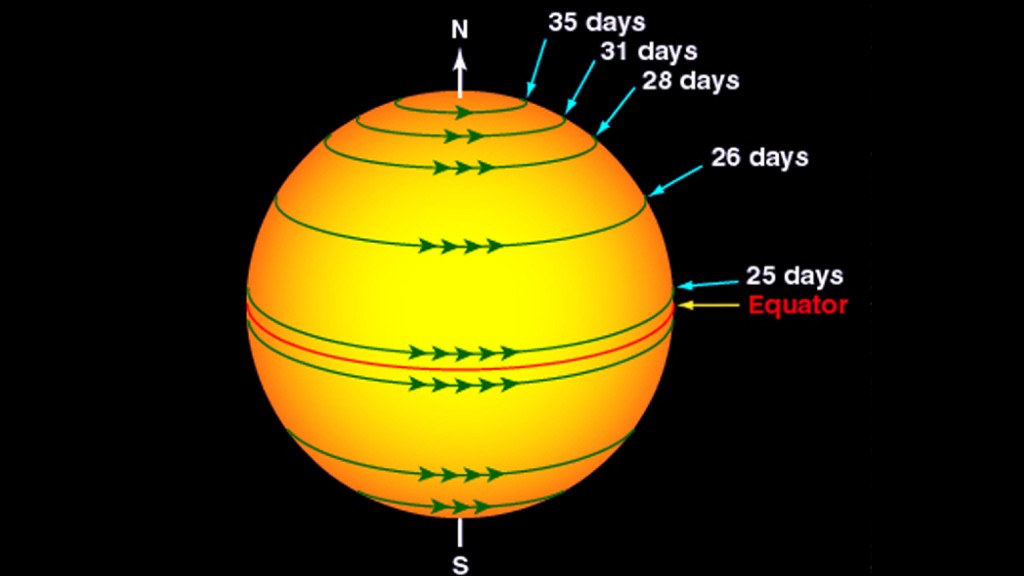

The sun experiences something called differential rotation. This means that its rotation proceeds at different rates depending on where you look at the star.

"Since the sun is a ball of gas/plasma, it does not have to rotate rigidly like the solid planets and moons do," according to NASA. "The source of this 'differential rotation' is an area of current research in solar astronomy."

Moving from the sun's poles to its equator, the time in which this area of plasma rotates shortens. The poles complete a rotation in 35 days, while the area just above the equator completes a rotation in just 25 days. This means that no area of the sun completes an orbit anywhere near as rapidly as our planet does.

Differences in rotation rates on our star aren't isolated to its surface, however. The layers of the sun's interior also rotate at different speeds with inner regions actually rotating more like the solid bodies of the inner solar system.

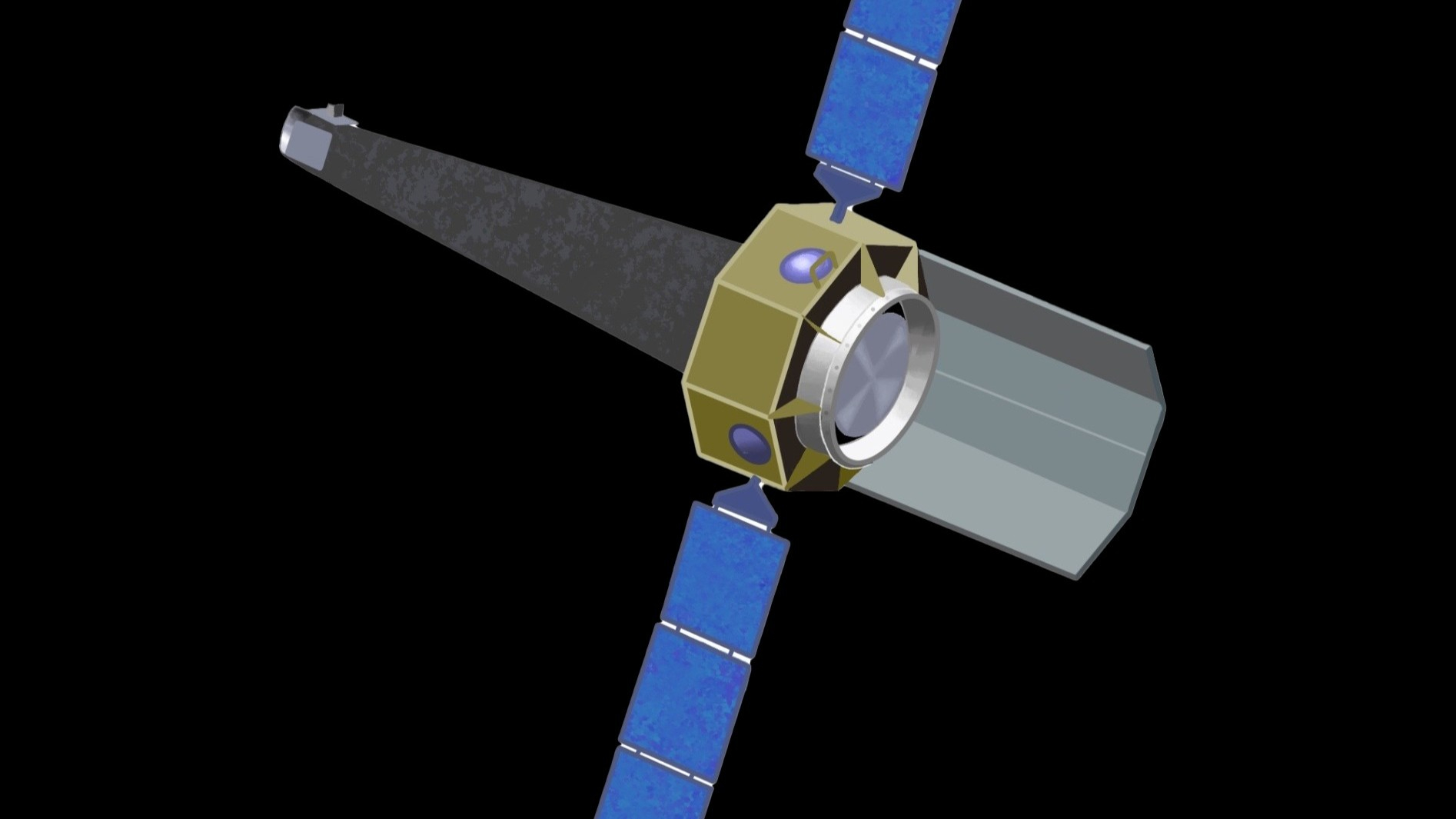

Astronomers estimate that the core of the sun actually rotates as rapidly as once a week, four times faster than its surface and intermediate layers, according to NASA's Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) page. This has led to solar scientists intensely studying the effects that arise as a result of different rotation rates throughout our star.

This type of rotation isn't unique to the sun or even to stellar bodies. The gas giants, Jupiter and Saturn, also experience differential rotation. This is not surprising given their gaseous composition. The ice giants Uranus and Neptune also have differential rotation — all spinning faster at their equators than they do at the poles.

Why does the sun rotate?

The sun's counterclockwise rotation and the counterclockwise rotation of the entire solar system (except two planets) is a result of its formation around 4.5 billion years ago.

At this point in the universe's history, the solar system was no more than a giant rotating disc of gas and dust. NASA Science suggests that an exploding star caused this to collapse forming a solar nebula.

At the center of this nebula, our sun formed incorporating 99 percent of the available matter with the outer dust clumps forming the planets. But, it incorporated something else too.

"The rotation of the sun is due to conservation of angular moment," National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) scientist Jeff Mangum said. "What this means is that the gas cloud from which the sun formed had some residual angular momentum that was passed on to the sun when it formed, which gives the sun the rotation that we observe today."

Additional resources

Discover how NASA and the ESA are investigating the core of the sun including the rate at which it rotates at NASA's SOHO page. Additionally, you can learn more about the solar system's rule breakers Venus and Uranus and their retrograde rotation at the Science Alert website.

Bibliography

"Galileo's sunspot letters". The British Library (2022).

"Solar Rotation Varies by Latitude". NASA (2013).

"Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo" (Doubleday, 1957).

"ESA, NASA’s SOHO Reveals Rapidly Rotating Solar Core". NASA (2017).

"Our Solar System". NASA Science, Solar System Exploration (2021).

"Why Does the Sun Rotate?". National Radio Astronomy Observatory (2020).

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.