What's the difference between an annular solar eclipse and a total solar eclipse?

We explore the incredible geometry behind total and annular solar eclipses.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Solar eclipses can be confusing.

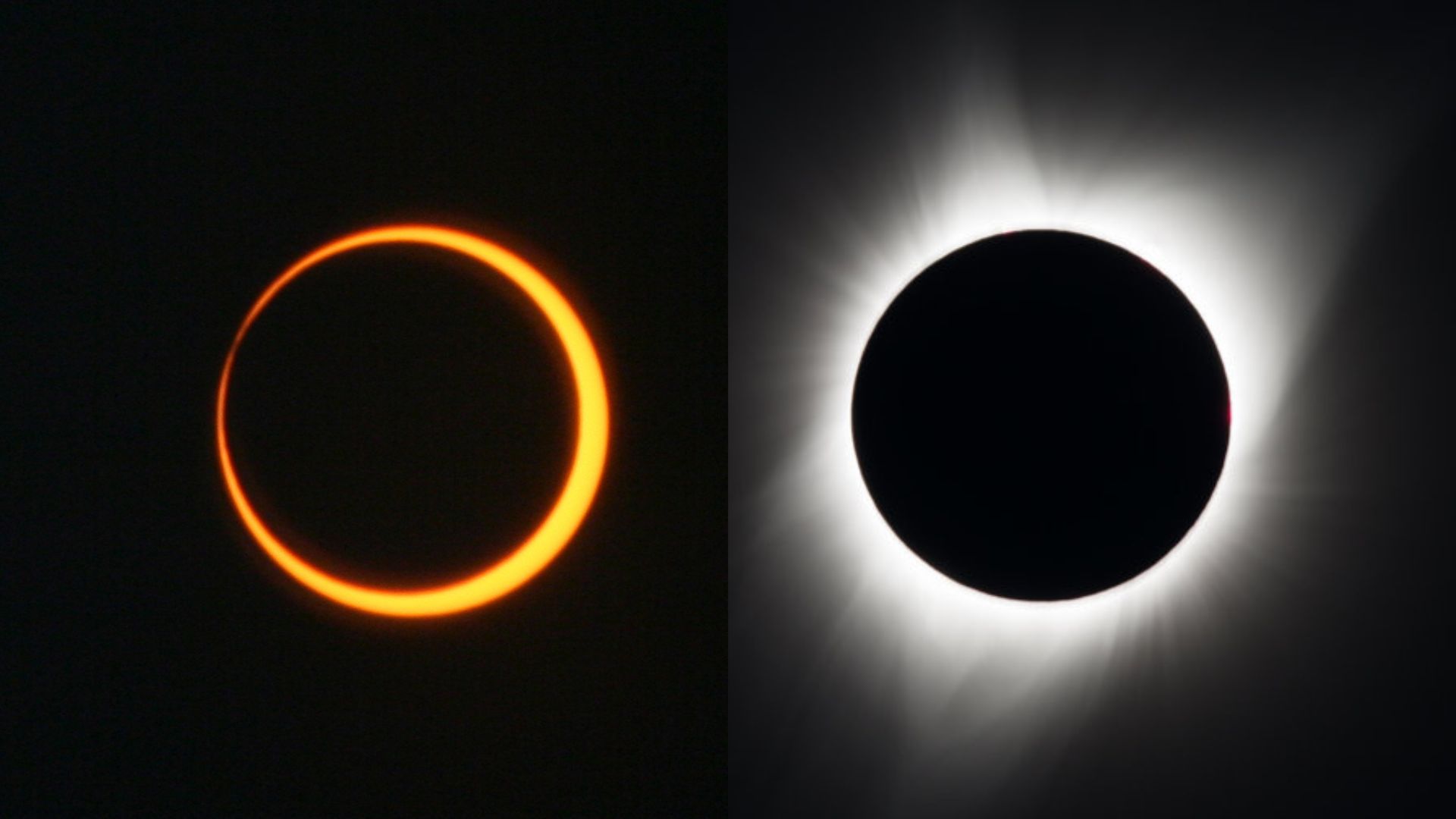

Almost everyone has heard of a total solar eclipse — also known as a total eclipse of the sun — but it's often mixed up with a "ring of fire" annular solar eclipse ("annular" means "ring"). Both types of solar eclipses are described by astronomers as central solar eclipses, but the exact geometrical differences between them are slight. However, those differences have a huge effect on what observers see, feel and experience. While one of the eclipse types can be described merely as a beautiful sight the other is an awe-inspiring multi-sensory experience.

Here's everything you need to know about the astronomical differences between a total solar eclipse and an annular solar eclipse to help prepare you for the upcoming annular solar eclipse on Oct. 2, 2024.

Article continues belowRelated: How to read and understand a solar eclipse map

Astronomical dynamics of solar eclipses

A solar eclipse occurs when the moon gets between the Earth and the sun, casting a shadow upon the Earth.

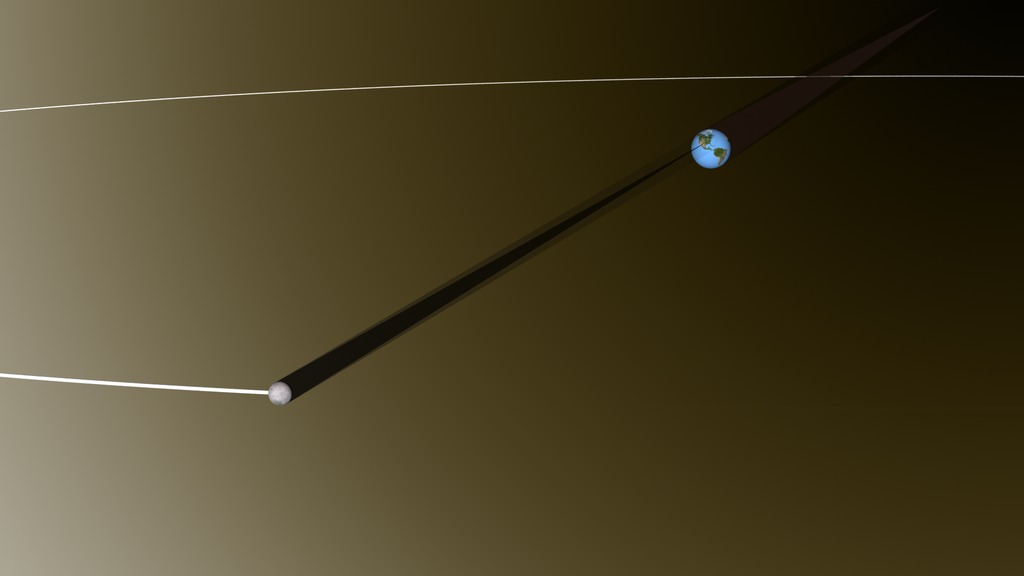

The basic reason solar eclipses happen is because the moon orbits Earth every 27 days, so often gets roughly between the Earth and the sun. However, solar eclipses do not happen every month. That's because the plane of the moon's orbit of Earth is tilted by 5º with respect to Earth's orbit of the sun. Twice each month the moon crosses the aptly-named ecliptic — the path of the sun through our daytime sky — at points that astronomers called nodes, according to EarthSky. If a new moon crosses the ecliptic it causes a solar eclipse, which it can do during every year's two eclipse seasons.

It's possible for the moon to block the sun because on average it's 400 times smaller than the sun, but also 400 times closer to Earth. The two objects thus have a very similar apparent size in our sky. It's an incredible coincidence, but in reality, it doesn't quite work out like that. Something else happens that results in two different kinds of solar eclipses.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Total vs. annular: The moon's three shadows

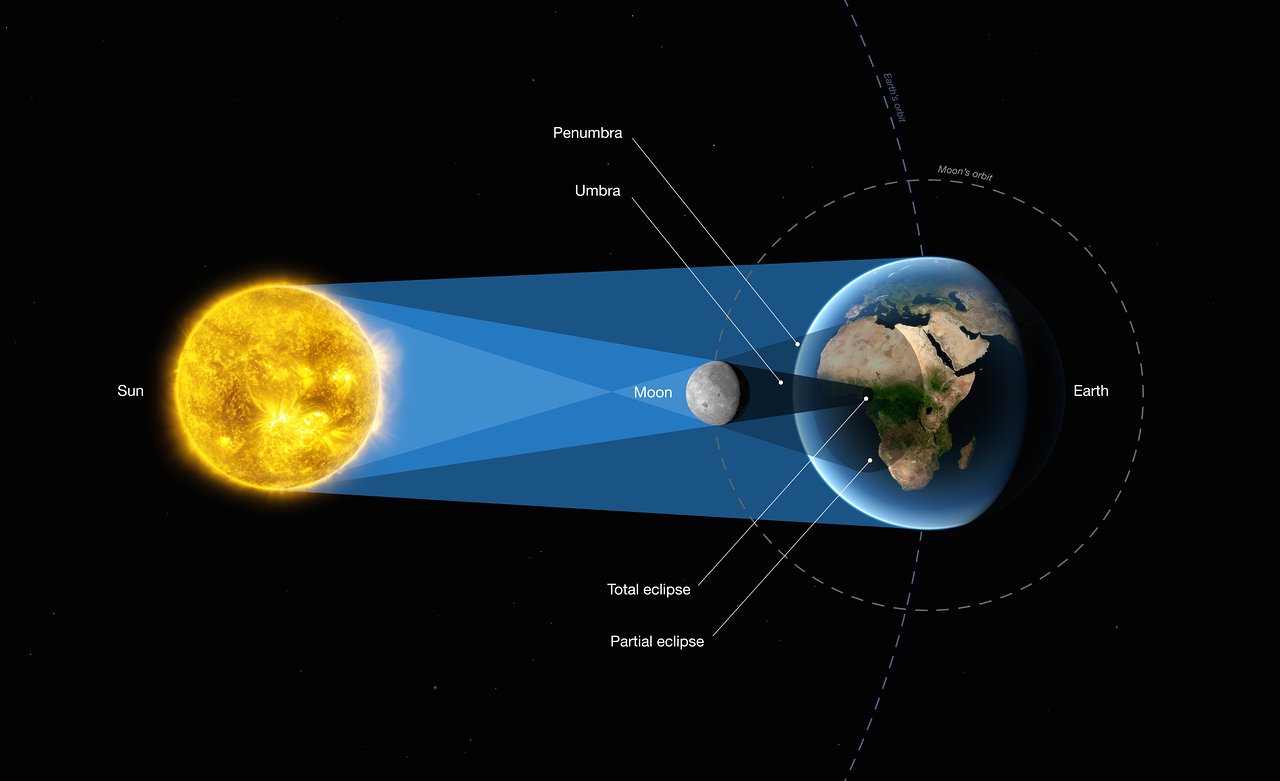

When the moon blocks a part of the sun as seen from Earth it casts a fuzzy shadow across a large part of Earth. This is the moon's penumbral shadow and if you stand within it and use solar eclipse safety glasses you can see a partial solar eclipse. However, the inner and darker part of the moon's shadow is what causes so-called central solar eclipses — annular and total.

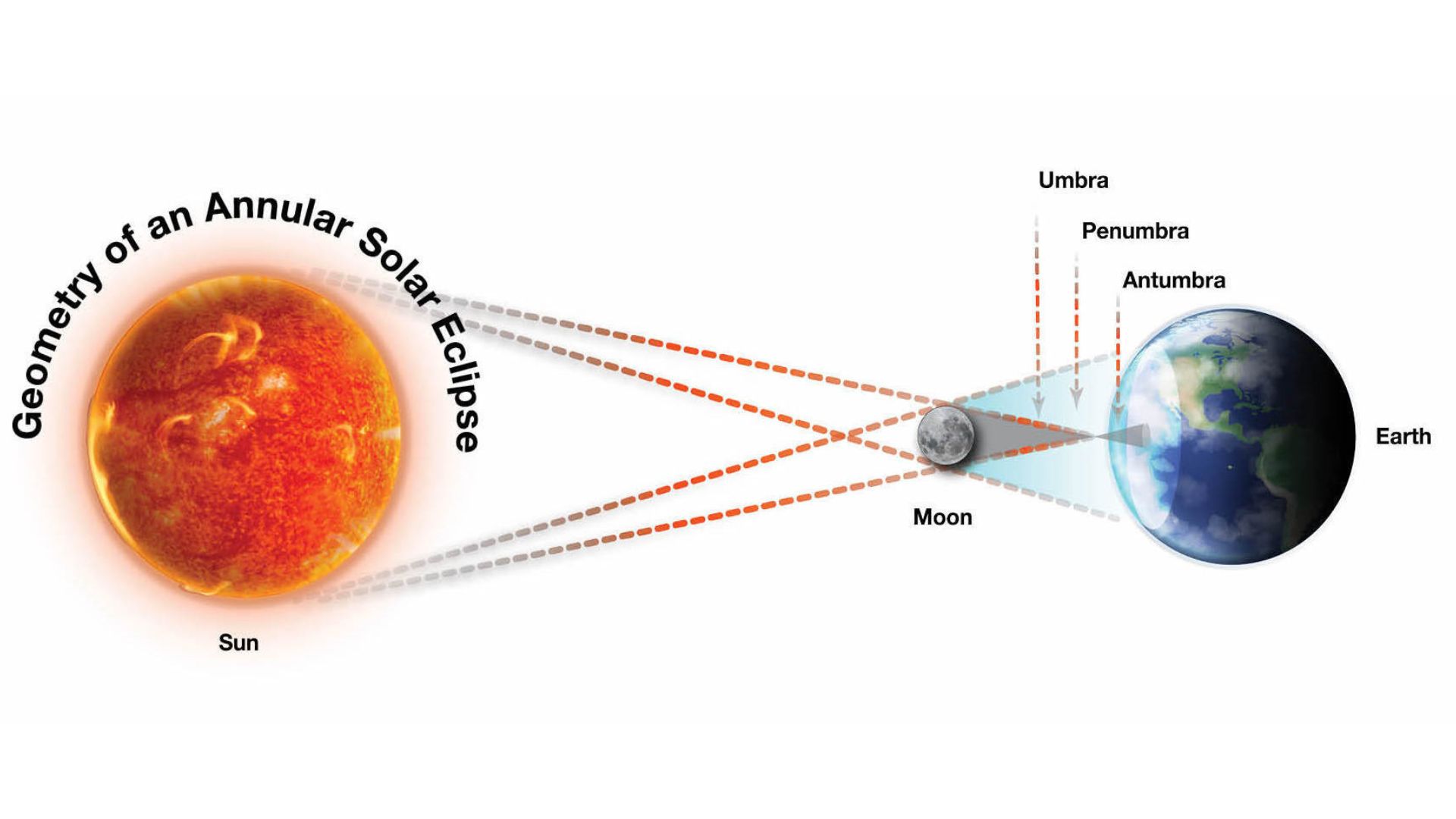

This inner shadow is narrow, cone-shaped and projected as a path across Earth in addition to (and within) the penumbra. That path moves across Earth's surface from west to east because the moon orbits west to east. During a total solar eclipse, the tip of that cone touches Earth and is called the umbra. It's also why eclipse-chasers are sometimes called umbraphiles, according to The Smithsonian. Those in this path of totality below experience a brief darkness in the day. During an annular solar eclipse, the umbral cone doesn't reach Earth so instead creates an antumbral shadow. Those in its path — the path of annularity — see a "ring of fire"' around the moon.

Total solar eclipses: The 'totality' phenomenon

A total solar eclipse occurs when the moon passes precisely between Earth and the sun while its apparent size is equal to, or bigger than, the sun. Dedicated eclipse-chasers aside, it's rare for anyone on Earth to experience a total solar eclipse. That's because you need to be on the day side of Earth during a solar eclipse, but also within the path of totality (the moon's umbral shadow), which is about 10,000 miles long, but only about 100 miles (or so) wide. Besides, all solar eclipses largely occur at sea (after all, over 70 percent of Earth is covered by the ocean).

The entire event takes about three hours, but it's the brief totality — when all of the sun's light is blocked (for up to six minutes, according to Timeanddate.com) — that's the reason eclipse-chasers will go anywhere to experience one. Totality gives viewers a chance to see the sun's outer atmosphere — the corona — with the naked eye, which is normally lost in the sun's glare. On either side of totality, it's possible to see beads of light streaming through the valleys of the moon, called Baily's beads. The last Baily's bead before totality begins creates a 'diamond ring' effect for a split-second as the corona emerges. The first Baily's bead as totality ceases causes another.

Totality causes a deep twilight, with observers also experiencing a noticeable drop in temperature about 20 minutes before totality because solar radiation in the umbra –the path of totality — is reduced.

Annular solar eclipses: The infamous 'ring of fire'

An annular solar eclipse is the most obvious evidence that the moon's orbital path around Earth is a slight ellipse. During each orbit of Earth, the moon reaches perigee (its closest point to Earth) and apogee (its farthest). When a perigee full moon coincides with a full moon it's often called a supermoon because it appears to be larger than usual. If a new moon is close to perigee while it's crossing the ecliptic then it causes a total solar eclipse while an apogee new moon — which appears smaller in the sky than usual — can't cover the sun's disk. The result is an annular solar eclipse during which a ring of sunlight is visible around the moon for a few minutes.

There is an exception to this. An annular solar eclipse can also occur when Earth is at perihelion, the closest to the sun that it gets during its own elliptical orbit, according to EarthSky.

This 'ring of fire" isn't as spectacular a sight as totality and must be viewed at all times through solar filters. Remember to NEVER look at the sun without adequate protection. Our how to observe the sun safely and what to look out for guide will help you get the most out of your sun-viewing ventures.

Additional resources

Want to look further ahead? You can find a concise summary of solar eclipses out to 2030 on NASA's eclipse website. Read more about solar and lunar eclipses on Eclipse Wise, a website dedicated to predictions of eclipses, and find beautiful maps on eclipse cartographer Michael Zeiler's GreatAmericanEclipse.com and interactive Google Maps on Xavier Jubier's eclipse website. You can find climate and weather predictions by meteorologist Jay Anderson on eclipsophile.com.

Bibliography

Bakich, M. and Zeiler, M. (2020). The Atlas of Solar Eclipses — 2020 to 2045. https://www.greatamericaneclipse.com/books/atlas-of-solar-eclipses-2020-to-2045

EarthSky, April 9, 2023. Why is there no eclipse every full and new moon? Retrieved Aug. 9, 2023 from https://earthsky.org/astronomy-essentials/why-isnt-there-an-eclipse-every-full-moon

Time and Date. (n.d.) What Is a Total Solar Eclipse? Retrieved Aug. 9, 2023 from https://www.timeanddate.com/eclipse/total-solar-eclipse.html

Jamie is an experienced science and travel journalist, stargazer and eclipse chaser who writes about exploring the night sky, solar and lunar eclipses, the Northern Lights, moon-gazing, astro-travel, astronomy and space exploration. He is the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com, author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners, co-author of The Eclipse Effect, and a senior contributor at Forbes.