Meet LICIACube, the small but mighty spacecraft that will watch NASA's epic DART asteroid crash

Italy's small LICIACube satellite will separate from NASA's DART spacecraft 10 days before the larger spacecraft is scheduled to strike the asteroid Dimorphos.

A small satellite will watch its robotic colleague smash into an asteroid, tracking the remarkable encounter and sending the footage back to Earth.

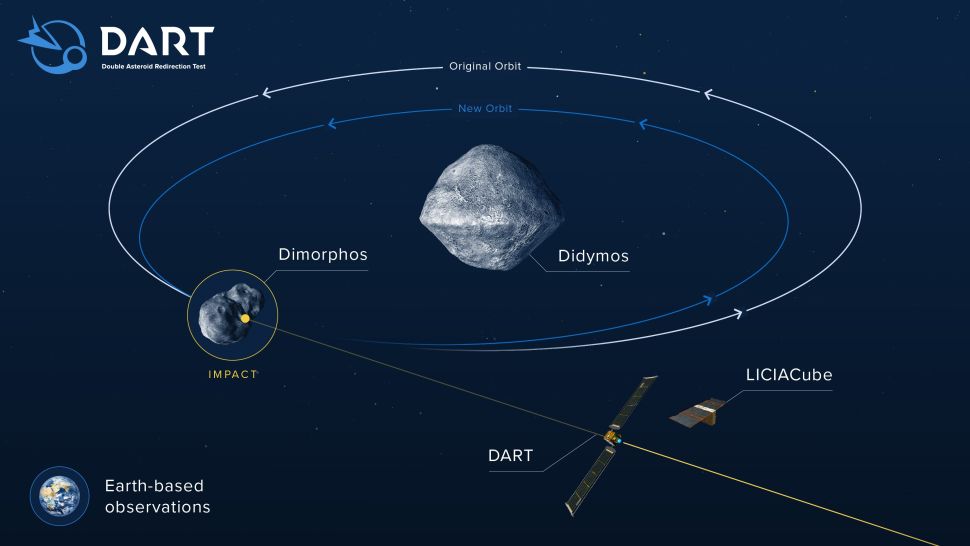

NASA and international agencies are coming together in the name of planetary defense. The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission led by the John Hopkins' Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) is the first mission up for this project. If all goes as planned, NASA's DART spacecraft will launch early Wednesday (Nov. 24) to reach a pair of near-Earth asteroids late next year.

DART's mission is simple: self-destruct by smashing into the smaller of the two space rocks, hopefully changing that object's orbit. But in order for scientists to see whether this novel collision tweaked the speed of the asteroid — which would carry major planetary defense implications for the future — a small satellite with Star Wars-inspired camera names will collect data from the sidelines. That cubesat is Italy's first deep-space mission, called LICIACube.

Related: If an asteroid really threatened the Earth, what would a planetary defense mission look like?

LICIACube, or the Light Italian CubeSat for Imaging Asteroids, isn't as large as its brave fellow. DART will be about the size of a school bus when its wings unfurl. LICIACube, which is armed with the LUKE (LICIACube Unit Key Explorer) and LEIA (LICIACube Explorer Imaging for Asteroid) optical cameras and weighs a total of about 31 pounds (14 kilograms), won't be much larger than a purse.

LICIACube is operated from its mission control center in Turin, Italy. The compact imaging satellite will travel with DART on its journey towards the asteroid Dimorphos, the small moon-like rock orbiting the larger asteroid Didymos. Engineers had to keep LICIACube small to allow it and DART to comfortably travel together along their space journey. "DART would not have been able to carry a much larger spacecraft to Didymos," Andy Cheng, lead investigator of DART, told Space.com via email.

Ten days before DART strikes Dimorphos, the spacecraft will release LICIACube and the small satellite will fire its thrusters to separate from DART in a final farewell. Unlike DART, LICIACube will survive the strike and fly past both asteroids.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To catch the special moment, LICIACube will need to be agile and get to a just-right distance from the collision for best viewing. The cubesat will have to mimic someone in a car on a highway wanting to look at another car stopped on the roadside, according to Simone Pirrotta, LICIACube project manager for the Italian Space Agency (ASI).

"The faster and the closer you are, the quicker you have to turn your head," Pirrotta told Space.com via email. "The pass distance must be appropriate: not so close to reduce the risk of an impact with ejected materials, but close enough for a good imaging."

LICIACube's LEIA is a high-resolution imager that can observe details of the impact plume and of the asteroid surface, according to Pirrotta. It can view the impact scene in black and white with great clarity, according to Cheng. LUKE, in contrast, has a larger field of view that allows it to follow the plume's full breadth during the whole pass. In addition, LUKE is equipped with red-green-blue color filters that can help scientists learn about the moonlet's physical properties.

DART has its own powerful camera, called DRACO. Four hours before impact, DART will switch into autonomous control where it will use DRACO's images to guide itself to crash onto Dimorphos, according to Cheng. But once the spacecraft strikes, DRACO will be destroyed and only LUKE and LEIA will be left behind to report back.

"The most interesting and critical pictures of the first phases of the mission, acquired before and just after the flyby, will be promptly transmitted," Pirrotta wrote. The data will flow through the Deep Space Network over to Turin, then to ASI's Science Operation Centre in Rome, Pirrotta added. That's when the data gets sent to NASA and APL.

"The DART image data leading up to impact will be streamed to Earth in real time, and we'll be watching," Cheng wrote. "The one-way light travel time delay from Didymos to Earth is only about 38 seconds."

LICIACube will store the image data and will continue transmitting images to Earth over the weeks and months following the crash.

The Italian and American teams will have independently operated their missions with strong cooperation up until contact, and that will continue after the collision. "The Italian and American scientists that already worked together in the modeling and prediction will then analyze the respective collected pictures and merge data for a more effective data exploitation," Pirrotta wrote.

The tiny spacecraft's next chapter will not last long. LICIACube is designed to survive at least six months orbiting the sun in near-Earth space, and Pirrotta expects that the cubesat will last even longer. However, the mighty-but-small spacecraft is not designed to withstand a second assignment in the solar system.

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.