What it was like to chase totality in South Texas

A clear view of the eclipse came down to pure luck as "Total Eclipse of the Heart" rang out.

Parts of Texas were the runaway favorite locations for a clear view of this year's total solar eclipse. It was ultimately, a last-gasp victory for some regions of the aptly-named Lonestar State — but only a few were lucky, as weather forecasts proved typically unreliable.

Precious minutes

From the beautiful South Llano River State Park near Junction, Texas I saw much of the partially eclipsed sun, yet only with the briefest of glimpses through thick clouds. I had no sightings of the sun's corona. And this was all while I hung on the edge of a stop-start weather system that lashed most of South Texas with low clouds. What had looked like a surefire clear eclipse 10 minutes before totality quickly became a lost cause.

Ground Zero

My "Plan A" for this eclipse had been the Ground Zero Festival in a rodeo arena near Bandera, the "cowboy capital of the world." I fancied a "We" eclipse, as its often called, and the city's 4 minutes and 9 seconds of totality would have been, by far, the longest of the seven other total solar eclipses I've witnessed. It was tremendous fun to experience the festival — particularly Friday's rodeo — but Bandera was projected to have the "un-Holy" Trinity for eclipse-chasers: Lower, middle and high clouds. "Plan B" was South Llano River State Park, which, by 6 a.m. local time on Monday morning, was predicted by all weather models to have clear skies for the big moment.

Northern Edge

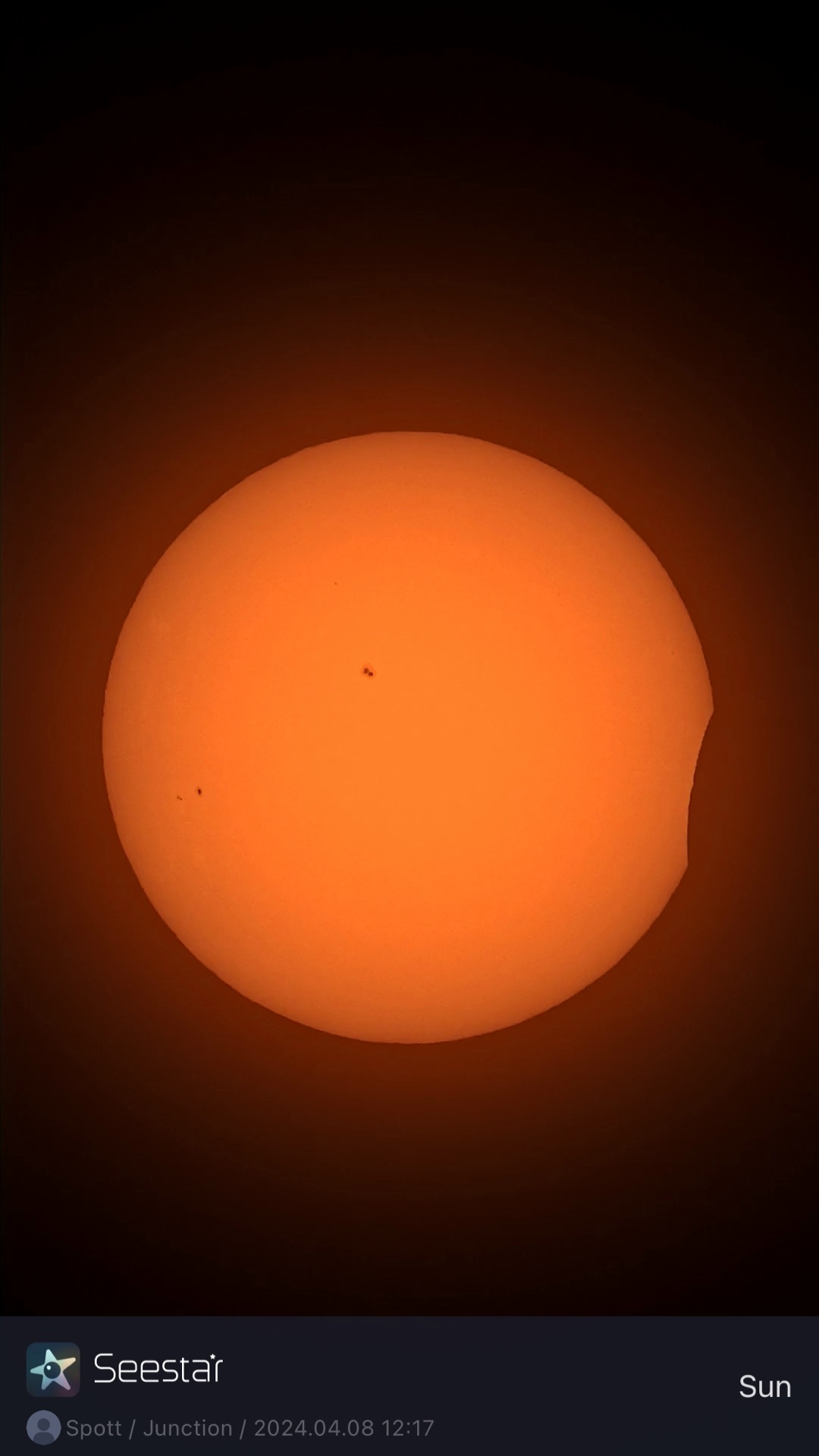

Knowing for many years that Junction was, statistically speaking, supposed to be the clearest part of the entire path of totality in the U.S, it was with a sense of inevitability that I and my posse of eclipse-chasers rose early to drive on empty roads to the path's northern edge. As we prepared for a 3 minutes and 12 seconds of totality, tripods were erected, camera filters were applied and eclipse-themed cowboy hats were donned. "First contact" was captured by team member Scott Spaulding using a SeeStar smart telescope. But, as totality neared, the telescope began to lose the sun behind a bank of low cloud rolling in from the southwest.

Dark totality

As we counted down the seconds to totality and light levels began to plummet, the size of the clouds meant a view of the sun's corona was merely a remote possibility. We did see a hint of a flash of the diamond ring on either side of a profound darkness, but little else. However, a total solar eclipse happens around you as well as above you. To witness totality in such a beautiful place was a treat. The birds and the bees around us reacted to totality with reverence; the turtle doves stopped cooing; the cardinals fell silent; the bees stopped buzzing. In fact, the only sound during totality was "Total Eclipse of the Heart" being played loudly nearby.

The disappointment was hard to shake, but so was the knowledge that it's better to be anywhere in the path of totality and not see the sun's corona than to be outside the path and have a clear view of a common partial eclipse.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Be Lucky

Sometimes, eclipse-chasing is as much about cloud-dodging as anything else. As we drove slowly back to Bandera, the lack of traffic was surprising. Did South Texas throw a party only for nobody to come? This eclipse turned out to be nothing like anyone expected, with warnings of crowds, chaos and guaranteed clear skies all wrong. And yet, it triple-underlined the two "musts" for eclipse chasers: be in every path of totality — and be lucky.

Jamie is an experienced science and travel journalist, stargazer and eclipse chaser who writes about exploring the night sky, solar and lunar eclipses, the Northern Lights, moon-gazing, astro-travel, astronomy and space exploration. He is the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com, author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners, co-author of The Eclipse Effect, and a senior contributor at Forbes.