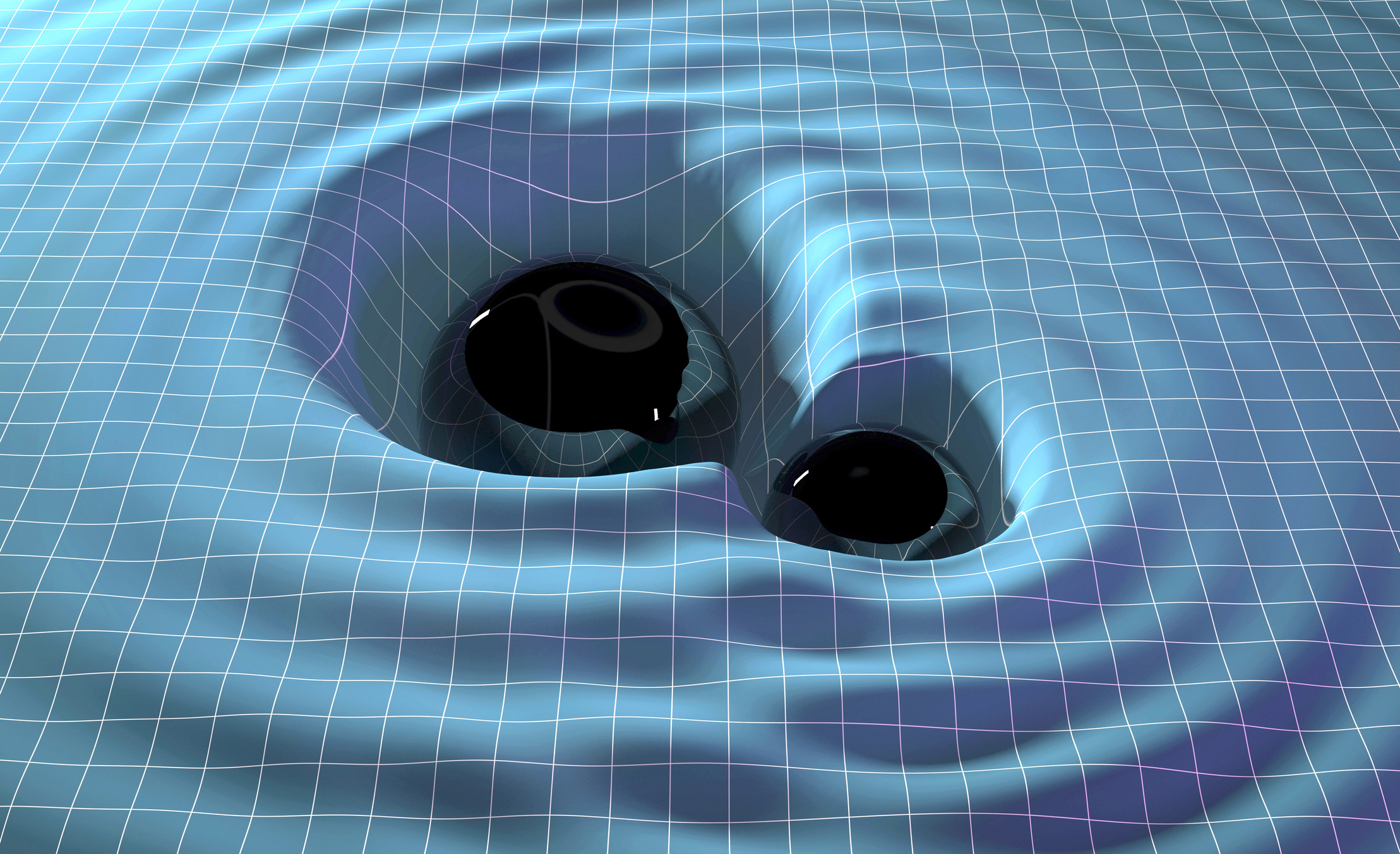

Double trouble! Two pairs of giant black holes spotted on collision course

NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory has spotted the first evidence of black holes in dwarf galaxies about to collide.

You wait for an age to see a colliding pair of black holes in a dwarf galaxy and then two come along at once! Astronomers have spotted not one but two dwarf galaxy black hole duos on separate collision courses, the first observational evidence of such a cosmic clash.

Just as the black holes are heading for a collision and merger that will leave a more massive black hole behind, the dwarf galaxies they sit in will also merge and form a larger galaxy. That means the findings could have important implications for our understanding of how these cosmic titans and the galaxies they inhabit grew in the early universe.

The scientists examined the colliding black hole pairings using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and found that as the dwarf galaxies are racing toward each other, they are pulling in gas that is "feeding" their inhabitant black holes causing them to grow even before the merger.

Related: The Milky Way's monster black hole is destroying a mysterious dust cloud

Dwarf galaxies are small galaxies that contain stellar mass equivalent to no more than around 3 billion times that of the sun. By comparison, the entire Milky Way is believed to contain a stellar mass of around 60 billion times that of our star.

Scientists think that in the first hundreds of millions of years after the Big Bang, the early universe was replete with these dwarf galaxies, most of which merged to form larger galaxies like ours.

"Most of the dwarf galaxies and black holes in the early universe are likely to have grown much larger by now, thanks to repeated mergers," Brenna Wells, a researcher at the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa who took part in the observations, said in a statement. "In some ways, dwarf galaxies are our galactic ancestors, which have evolved over billions of years to produce large galaxies like our own Milky Way."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

These early galaxies have thus far been impossible to observe due to the fact they are extremely faint and are located at great distances away. Astronomers have, however, seen closer dwarf galaxies in the process of merging but there has been no sign of black holes in those galaxies until now.

"Astronomers have found many examples of black holes on collision courses in large galaxies that are relatively close by," Marko Micic, also a researcher at the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa and a member of the team, said in the statement. "But searches for them in dwarf galaxies are much more challenging and until now had failed."

To overcome the challenge of spotting black holes in merging dwarf galaxies, Micic and the team conducted a systematic survey of deep Chandra X-ray observations and then compared them with both infrared data from NASA's Wide Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and optical data from the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT).

Because the material around the black holes is heated to millions of degrees, it produces large amounts of high-energy light in the form of X-rays, which Chandra is adept at spotting. Hunting for pairs of bright X-ray sources in colliding dwarf galaxies, the researchers spotted two examples.

The closest pair of colliding dwarf galaxy black holes are located 760 million light-years from Earth in the galactic cluster Abell 133. These dwarf galaxies appear to be in the later stages of merging with the tidal effects of the collision causing the formation of a long tail of material.

This tail of gas and dust led the scientists to give this collision the nickname "Mirabilis" which is a reference to an endangered species of hummingbird with an exceptionally long tail. They only selected one name for this collision due to the fact it is nearly complete and thus practically represents a single object.

The more distant merger is located around 3.2 billion light-years away in the galactic cluster Abell 1758S and is in an earlier state of collision. This means the scientists gave the dwarf galaxy components of the collision two names, "Elstir" and "Vinteuil." Both names refer to fictional artists from Marcel Proust's "In Search of Lost Time."

This more distant collision doesn't have a tidal tail, but it has developed another interesting collision-caused structure, a bridge of stars and dust stretching to connect the two dwarf galaxies.

The team of astronomers will now continue to observe these collisions to watch how they proceed and the effect on the dwarf galaxies.

"Using these systems as analogs for ones in the early universe, we can drill down into questions about the first galaxies, their black holes, and star formation the collisions caused," research co-author and University of Alabama astronomer Olivia Holmes, said.

The team's research is published on the paper repository ArViX and has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.