Can a star bounce back from the verge of death? One star did — or at least appeared to.

In early 2019, the red supergiant Betelgeuse began to dim. Some observers predicted that the dimming was a harbinger of the star’s end: That it was the first warning sign that Betelguese was about to go supernova.

Astronomers are now certain that isn’t true. Images released by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) on Monday (Oct. 23) clearly show Betelguese returned to normal after the event.

Related: Is the puzzling star Betelgeuse going to explode in our lifetime after all?

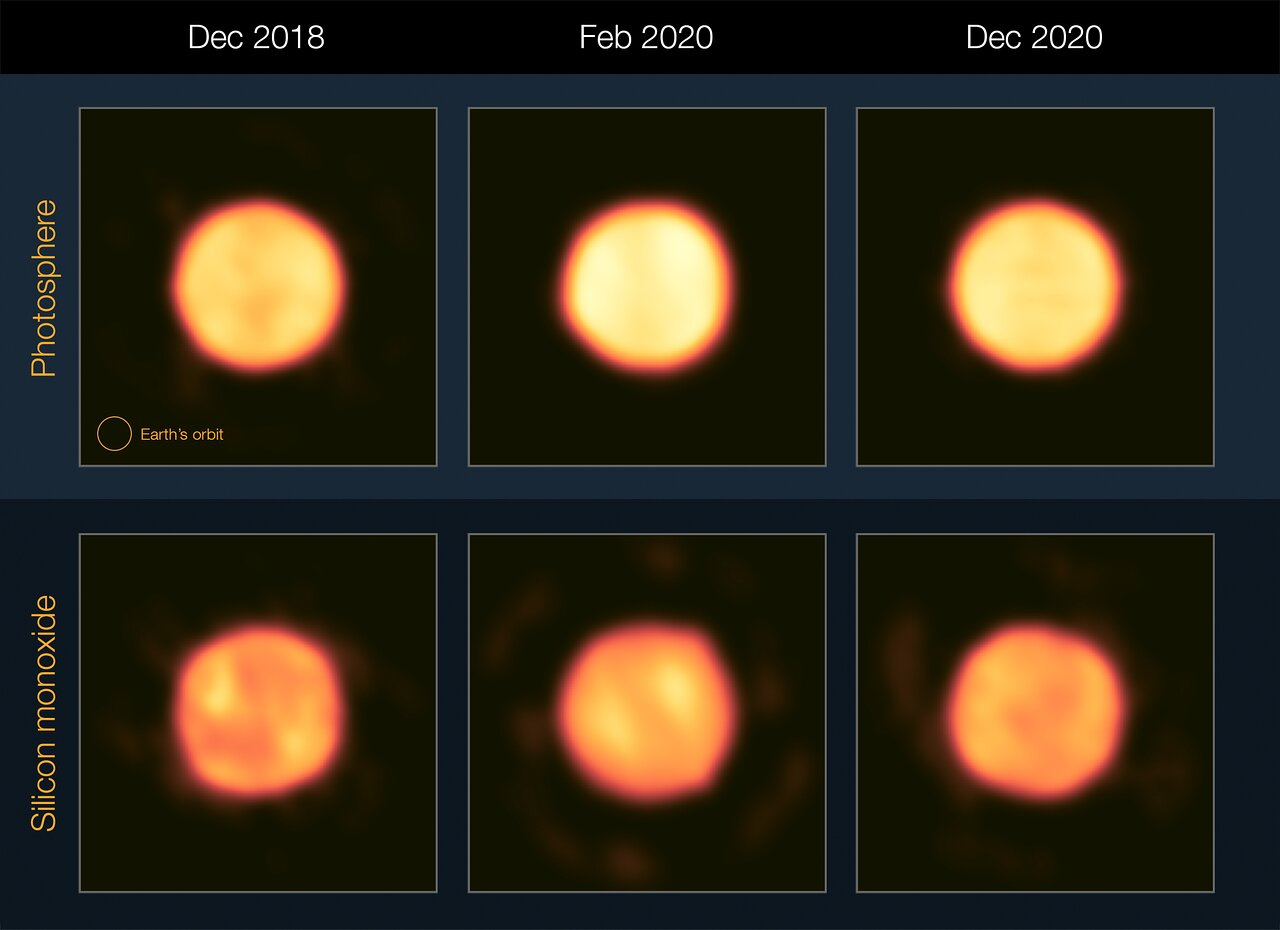

The images are thanks to a team from France’s Université Côte d’Azur, who snapped high-resolution photographs of Betelgeuse between December 2018 and December 2020. Using the MATISSE (Multi Aperture mid-Infrared Spectroscopic Experiment) instrument on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope Interferometer in northern Chile, these astronomers caught the star before, during, and after the dimming event.

Although the star as a whole appeared to darken, Betelgeuse’s photosphere seemed to actually brighten during the event. The Université Côte d’Azur astronomers say this observation is consistent with a likely theory, supported by observations, that Betelgeuse dimmed from our view due to a burst of dust, in the form of silicon monoxide, coming from the star. In turn, that burst might be related to a sudden cooling of the star's surface.

"The changes in the structure of the photosphere and the silicon monoxide are consistent with both the formation of a cold spot on the star’s surface and the ejection of a cloud of dust," the statement reads.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If the theory holds true, it would also tie into the results of a 2021 study about the star, which had suggested Betelgeuse basically burped out a bubble of gas. Astronomers observing the star at that time had concluded that some gas might've erupted from its surface due to a sudden drop in temperature.

The sudden chill, according to the 2021 results, would have also been stark enough to cool the departing gas enough for some to condense into solid dust. The dust would have then spread out to create a veil before the star, dimming it from our vantage point — and the MATISSE images therefore support that theory. Plus, the images also therefore indicate that dust — the same dust that can go on to feed newborn star systems — can actually form very close to stars.

Nonetheless, supergiants like Betelgeuse, late in their stellar lives, still present astronomers with a large number of mysteries. And if another star within our galaxy is about to go supernova, astronomers — who haven’t observed such a star death since the 17th century — don’t entirely know what to expect.

A study of the MATISSE images of the great dimming of Betelgeuse was published in the journal "Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters" in September 2023.

Rahul Rao is a graduate of New York University's SHERP and a freelance science writer, regularly covering physics, space, and infrastructure. His work has appeared in Gizmodo, Popular Science, Inverse, IEEE Spectrum, and Continuum. He enjoys riding trains for fun, and he has seen every surviving episode of Doctor Who. He holds a masters degree in science writing from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP) and earned a bachelors degree from Vanderbilt University, where he studied English and physics.