Is the puzzling star Betelgeuse going to explode in our lifetime after all?

What is the evidence for Betelgeuse being in its death throes?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A new unpublished study is making waves on the internet by claiming that one of the brightest stars in the night sky might die in a spectacular explosion within our lifetime.

The study, currently available on the online pre-print serverarXiv, conjectures that the red giant star Betelgeuse, the left shoulder of the constellation Orion also known as Alpha Orionis, may have less than three hundred years' worth of fuel left in its core. When the star burns through those last drops, its core will collapse into a black hole and in the process blast out the star's outer layers at enormous speeds of up to 25,000 miles (40,000 kilometers) per second. This fiery demise is what astronomers call a supernova explosion, and in the case of Betelgeuse, it will be a spectacular sight for observers on Earth. Since the star is only 650 light-years from Earth, those layers of gas and dust will shine as bright as the full moon in our sky for several weeks.

The problem is that most astronomers don't think that Betelgeuse is ready to go bang just yet. So what makes the researchers behind the new paper think otherwise?

Related: Odd supergiant star Betelgeuse is brightening up. Is it about to go supernova?

Betelgeuse is undoubtedly a red giant star that has already burned through its primary fuel hydrogen and is now fusing helium in its core into heavier elements. The point at which a star runs out of hydrogen in its lifetime is unmissable. Stars short on hydrogen need to put extra energy into igniting the helium produced during the fusion of hydrogen, which forces them to expand dozens of times beyond their original size. In the process, they also become cooler and redder.

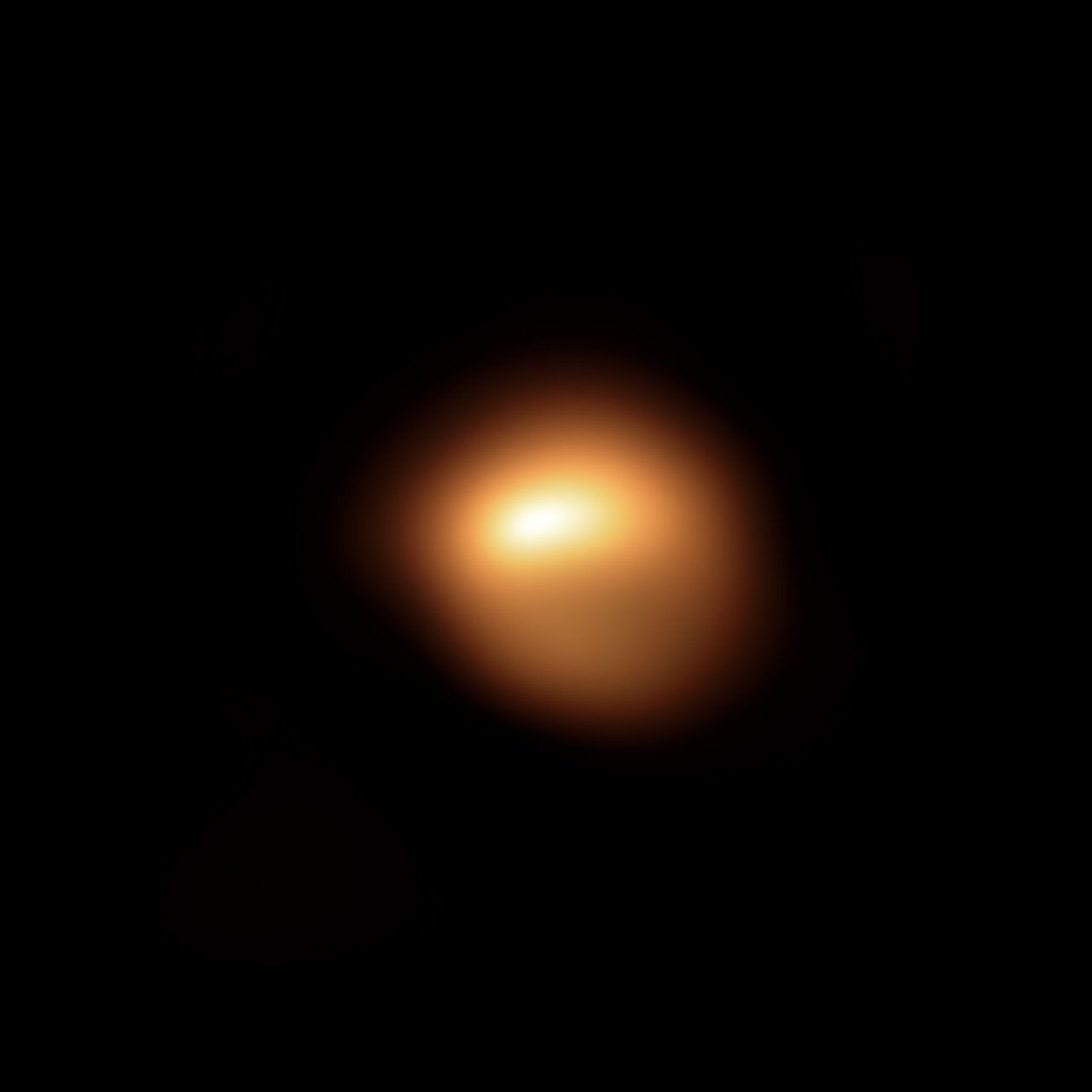

Astronomers know that Betelgeuse is huge. If it were to sit at the center of our solar system, the scorching gas in its outer atmosphere would reach far enough to engulf even the planet Jupiter. However, the exact width of Betelgeuse is hard to measure. That's because instead of being one rather smooth ball of plasma, Betelgeuse is a lumpy clump of boiling gas bubbles shrouded in burped out dust clouds. To measure its diameter is therefore not easy, yet, the case for determining Betelgeuse's remaining lifetime rests on the star's size.

In the new controversial study, a team of astronomers led by Hideyuki Saio from the Tohoku University in Japan suggests that Betelgeuse is larger than what most researchers believe. This could be possible as Betelgeuse is known to pulsate — expand and shrink, dim and brighten up — at regular intervals. Most obviously, Betelgeuse's brightness swings up and down every 420 days. Astronomers attribute this brightening to the periodical expansion of the star's envelope, or roughly spherical outer region, in a phenomenon known as the fundamental mode.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There are other quirks in Betelgeuse's behavior, also appearing on a regular basis, which astronomers attribute to additional turbulent processes taking place inside the dying star. One of those additional variations takes place on a 2,200-day cycle, and astronomers have no explanation for it. The team led by Saio therefore proposed that this 2,200-day oscillation could, in fact, represent Betelgeuse's main pulsation mode while the 420-day brightness variation could be a secondary quirk.

Such a scenario, however, requires Betelgeuse to be up to one third wider for these models of its evolution to work, Saio told Space.com in an email.

"To explain the 2,200-day period as fundamental mode requires a much larger radius than the case of fitting the 420-day [period] with fundamental mode," Saio wrote in an email. "A larger radius with a range of observed surface temperature means the intrinsic brightness of Betelgeuse to be higher than previously thought."

But for Betelgeuse to be as wide as the models require, it would also have to be in a later stage of its life, already done burning helium and instead running on carbon, which arose from the previous fusion of helium atoms. Whether a red giant star is burning helium or carbon makes a big difference in terms of how much life it has left. The helium-burning phase of a red giant star's life lasts tens of thousands of years. When carbon-burning switches on, the end is nigh, at least in cosmic terms, and might come within a few thousand years.

"Although we cannot determine exactly how much carbon remains right now, our evolution models suggest that the carbon exhaustion would occur in less than 300 years," Saio wrote. "After the carbon exhaustion, fusions of further heavier elements would occur in probably a few tens of years, and after that the central part would collapse and a supernova explosion would occur."

That would certainly be exciting for skywatchers. The last time a nearby star went supernova was in 1604. Although stars explode somewhere in the universe on a daily basis, most of them are too far away to be visible without powerful telescopes.

But the question remains: What else is there but models to make Saio and his colleagues think that Betelgeuse is larger than what other astronomers think?

In their paper, the researchers point out two measurements of Betelgeuse's size to support their theory. But this is exactly where the paper has drawn criticism from other astronomers.

Miguel Montargès, a postdoctoral fellow at the Laboratory of Space Studies and Instrumentation in Astrophysics at the Paris Observatory who published papers on Betelgeuse based on observations by the Very Large Telescope in Chile, told Space.com in an earlier interview that "of the tens of measurements of Betelgeuse, [Saio and his colleagues] have selected only two."

László Molnár, an astronomy research fellow at the Konkoly Observatory in Budapest, Hungary, who also published several papers on Betelgeuse said that the measurements picked by Saio and his colleagues to support their theory were likely influenced by clouds of dust and gas around the star that make Betelgeuse appear bigger.

"If we look at the sun, we see a well-defined surface with a very crisp edge," Molnár told Space.com in an email. "But Betelgeuse being a red supergiant, is extremely fluffy and puffy, and the photosphere, what we would call its 'surface,' is hidden beneath multiple layers of molecular gas and clouds of dust."

Violent expulsions of these materials are typical for red giant stars. In the case of Betelgeuse, astronomers observed one such massive cloud emerge from within the star in 2019, causing the star to temporarily dim.

Molnár and his team made their own measurements of Betelgeuse's size, which are more aligned with what most scientists think.

The release of Saio's paper coincides with an unusual brightening of Betelgeuse that led some enthusiasts to speculate that the star might be about to explode. But neither Molnár nor Montargès are convinced. Betelgeuse, Montargès said, is actually too bright to be in its death throes due to the fact that expulsions of material typically make older red giants gradually dim. Betelgeuse, on the contrary, despite its regular pulsations, has been a fixture in the top ten brightest stars of our sky for at least the past 100 years.

The paper has not yet been peer-reviewed and published, so some of its shortcomings might get addressed before it gets officially released.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.