Watch the BepiColombo probe zoom by Venus on its way to Mercury in this new video

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

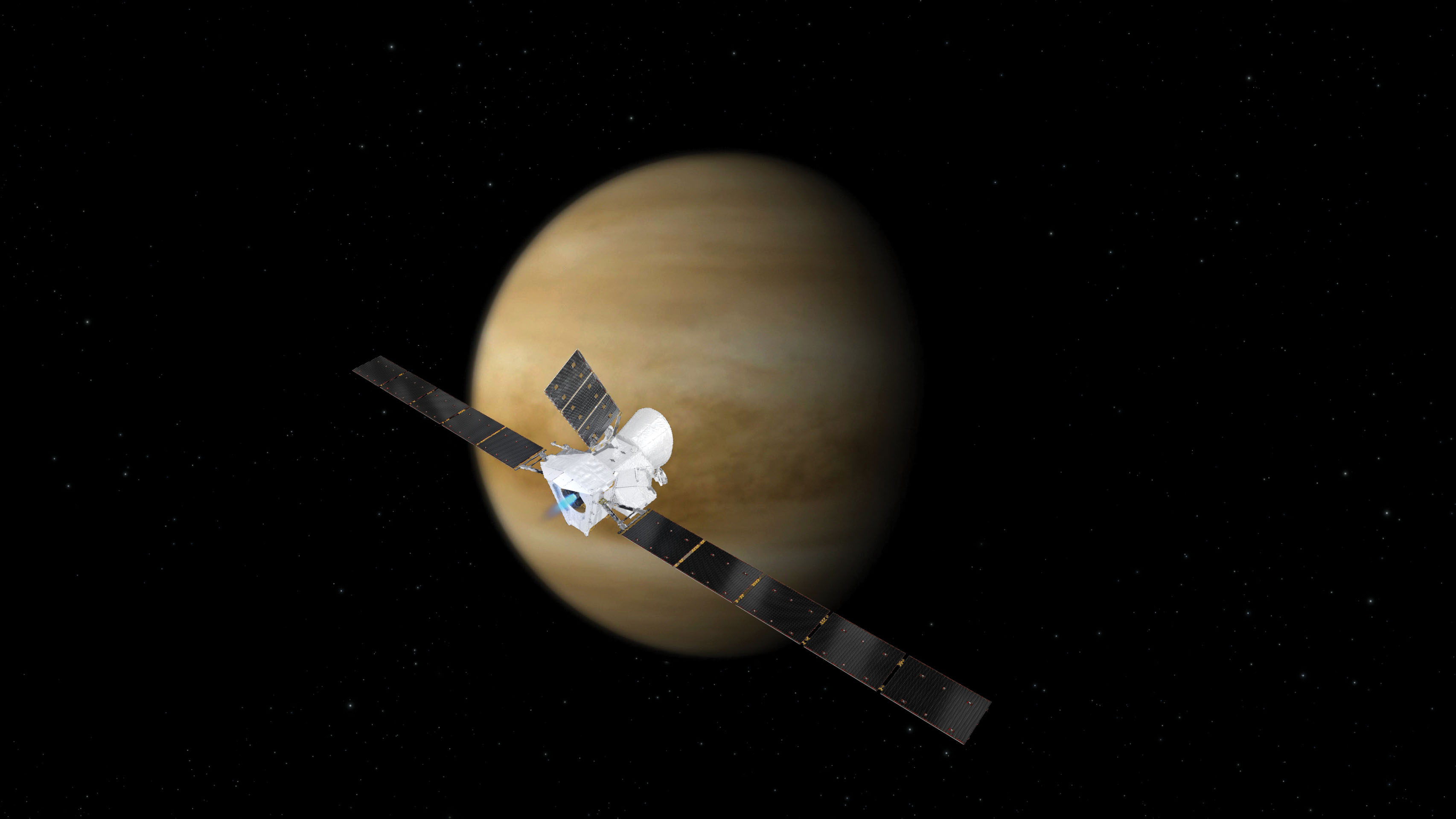

The European-Japanese BepiColombo spacecraft headed to Mercury can be seen flying low above the atmosphere of Venus in a new video released today (Aug. 12).

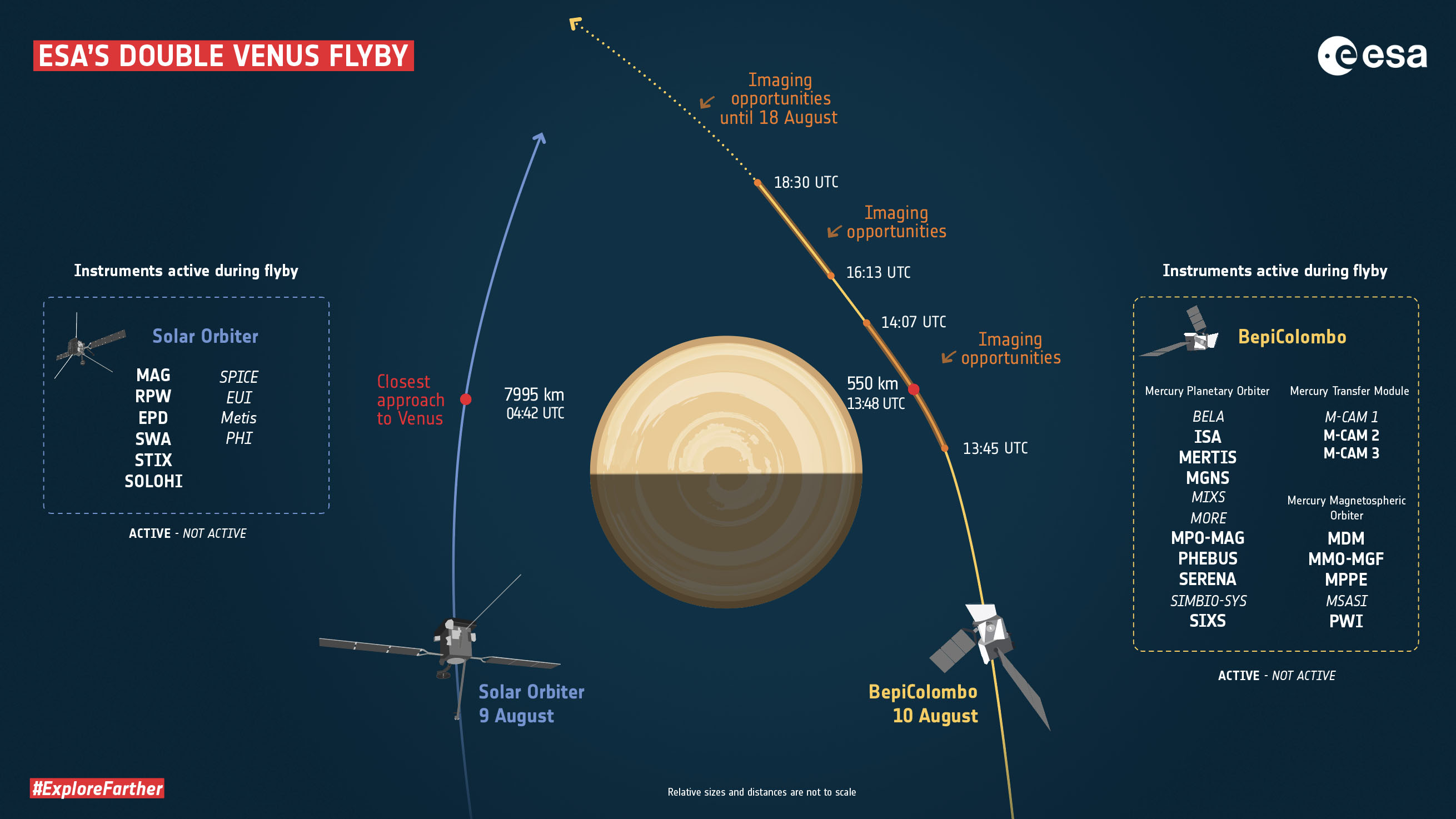

The BepiColombo team created the video from 89 images taken by the spacecraft during its flyby of the planet on Tuesday (Aug. 10). This flyby, the second for BepiColombo at Venus, took the spacecraft 20 times closer to the hot planet's surface than the first did, in October 2020.

During this week's maneuver, which adjusted the spacecraft's trajectory with the help of Venus’ gravity, BepiColombo flew 340 miles (550 kilometers) above the surface of the planet. That is close enough for its sensitive instruments to make valuable measurements of the chemical composition of Venus’ cloudy atmosphere.

Article continues belowIn fact, during this flyby, BepiColombo got closer to the surface of Venus than the Japanese orbiter Akatsuki, the only spacecraft currently studying Venus. The closest point in Akatsuki’s orbit around Venus is at about 620 miles (1,000 km). The mission is a partnership between the by the European Space Agency (ESA) and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

Related: Watch Venus glide by in this serene video from the BepiColombo

The images used in the video were taken by three 'selfie' cameras mounted on BepiColombo's propulsion module between 9:41 a.m. EDT (1341 GMT) on Aug. 10 and 8:21 a.m. EDT (1221 GMT) on Aug. 11. The video covers BepiColombo's pass above Venus from a distance of 2,140 miles (3,450 km) through the closest approach at 340 miles and ends with the cameras at a distance of about 370,000 miles (600,000 km) from Venus as the spacecraft moves away from the planet.

The primary task of the selfie cameras was to monitor the deployment of the spacecraft's solar arrays and antennas following its launch in October 2018, ESA BepiColombo project scientist Johannes Benkhoff told Space.com. The team, however, is making use of these cameras to take snapshots during BepiColombo's seven-year cruise through the inner solar system.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The three black-and-white cameras provide images with a relatively low resolution of 1024 by 1024 pixels, comparable to an early-2000s flip phone. The cameras' technical limitations are clear in the video.

"Venus is much too bright for these cameras to see detailed structures in the atmosphere of Venus," Benkhoff said.

BepiColombo also carries a high-resolution stereoscopic camera, but that cannot be used during its cruise because of the mission's configuration during transit. The spacecraft is actually a stack of three elements — a European orbiter, a Japanese orbiter and a transfer module that links them. Some instruments on the European orbiter, including the high-resolution stereoscopic camera, are hidden by the transfer module. Some of the instruments on the Japanese orbiter, meanwhile, are covered by a protective sun shield.

However, nine out of the 11 instruments on board of the European orbiter were operational during the close Venus flyby, which meant mission scientists could test these devices at about the same distance from Venus as they will need to operate at Mercury.

The team hopes the flyby will provide some unique measurements, complementary to what the Japanese orbiter Akatsuki is able to detect.

"Our infrared spectrometer, MERTIS, observed the middle atmosphere of Venus during the flyby," Benkhoff said. "We want to look for some components, such as carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide and other aerosols, which has not been done before with this type of instrument."

The scientists are currently analyzing the data, even as they continue preparing for BepiColombo's next flyby, the mission's first at Mercury, which will take place on Oc. 2. This flyby will see BepiColombo zip by Mercury at a distance of only 125 miles (200 km).

"To be able to test our instruments now at Venus was an ideal preparation," Benkhoff said. "Because Mercury is a darker planet, we hope that even the selfie cameras will perform better there and will enable us to see some structures on the surface."

The October flyby will mark the first visit to Mercury by any spacecraft since the end of NASA's Messenger mission in 2015.

BepiColombo has to perform a total of nine gravity-assist flyby maneuvers that use the gravity of planets to help slow down the spacecraft and adjust its trajectory. The first flyby, at Earth, took place in April 2020.

In addition to the two Venus flybys there will be six at Mercury itself before the spacecraft slows down enough to enter the correct orbit around the planet, which will occur in 2025. The transfer module will then be jettisoned and the two orbiters will start their explorations of the scorched, rocky planet separately.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.