Autumnal equinox 2023 brings fall to the Northern Hemisphere today (Sept. 23)

When is the first day of fall in 2023?

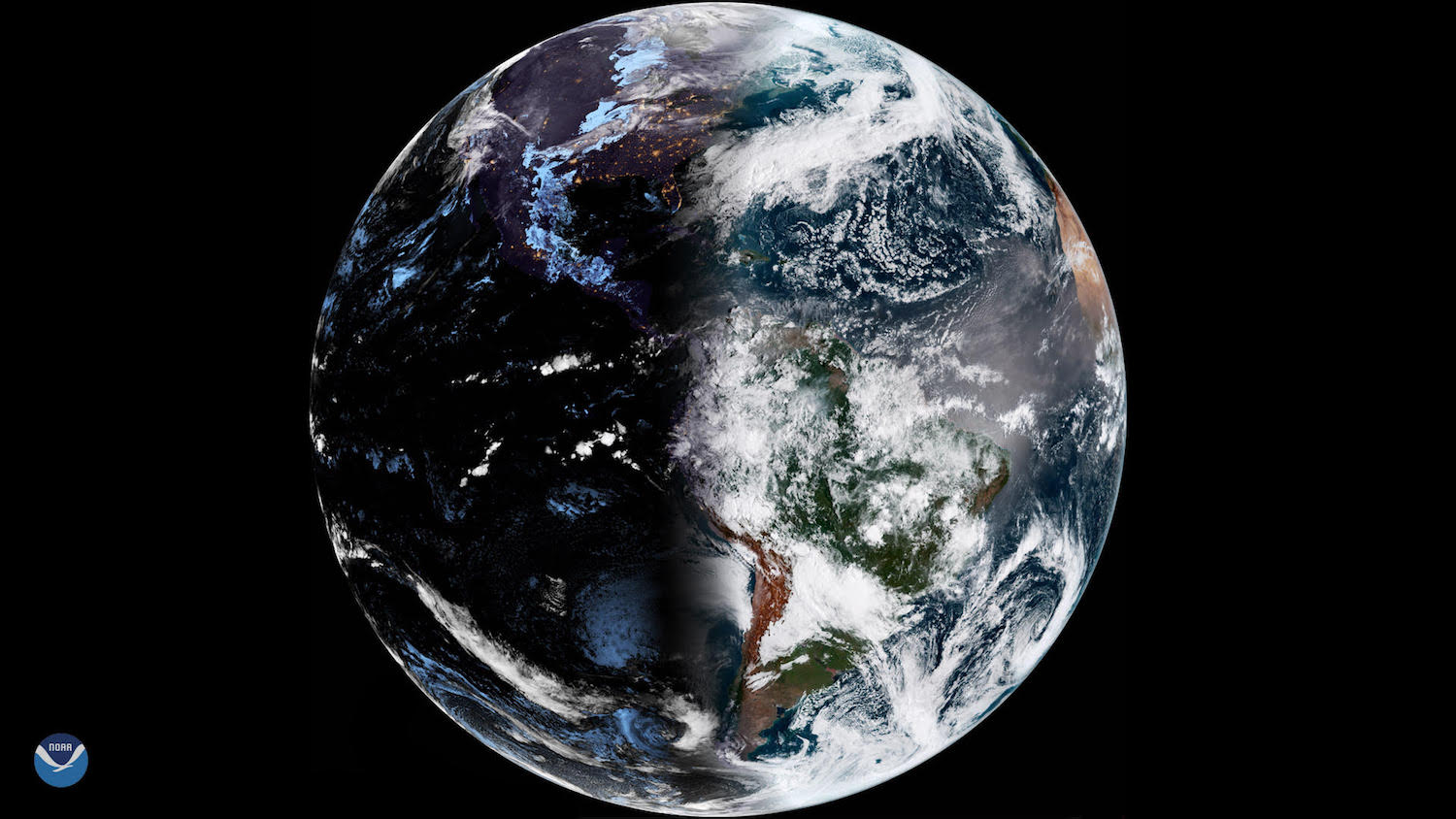

A carefully worded answer is that today (Sept. 23), at 2:50 a.m. EDT (0650 GMT), autumn began astronomically in the Northern Hemisphere, and spring starts in the Southern. The sun is currently migrating south, having spent the previous six months shining directly on the northern half of our planet.

So, at the official start time of autumn, the sun would appear directly overhead from a ship in the Laccadive Sea, positioned on the equator, 170 miles (275 kilometers) northeast of Addu City in the Maldives.

We call this event an equinox, from the Latin for "equal night," alluding to the fact that day and night are then of equal length worldwide. But this is not necessarily so.

Related: What is an equinox?

Not so equal

The definition of the equinox as being a time of equal day and night is a convenient oversimplification. For one thing, it treats night as simply the time the sun is beneath the horizon, and completely ignores twilight.

If the sun were nothing more than a point of light in the sky and if Earth lacked an atmosphere, then at the time of an equinox the sun would indeed spend one half of its path above the horizon and one half below. But in reality, atmospheric refraction raises the sun's disk by more than its own apparent diameter while it is rising or setting. Thus, when we see the sun as a reddish-orange ball just sitting on the horizon, we're looking at an optical illusion.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It is actually completely below the horizon.

In addition to refraction hastening sunrise and delaying sunset, there is another factor that makes daylight longer than night at an equinox: Sunrise and sunset are defined as the times when the first or last speck of the sun's upper limb — not the center of its disk — is visible above the horizon.

And this is why, if you check your newspaper's almanac or weather page this Saturday (or Friday, if you live on the U.S. Pacific Coast) and look up the times of local sunrise and sunset, you'll notice that the duration of daylight, or the amount of time from sunrise to sunset, still lasts a bit more than 12 hours, and not exactly 12 as the term "equinox" suggests.

In Richmond, Virginia, for instance, sunrise is at 6:58 a.m. and sunset comes at 7:05 p.m. So, the amount of daylight is not 12 hours, but rather 12 hours and 7 minutes. Not until Sept. 26, are days and nights in Richmond truly equal (sunrise that day is at 7:00 a.m. and sunset comes 12 hours later).

And at the North Pole, the sun currently is tracing out a 360-degree circle around the entire sky, appearing to skim just above the edge of the horizon. At the moment of this year's autumnal equinox, it should theoretically disappear completely from view, and yet its disk will still be hovering just above the horizon. Not until 52 hours and 10 minutes later will the last speck of the sun's upper limb finally drop completely out of sight.

This strong refraction effect also causes the sun's disk to appear oval when it is near the horizon. The amount of refraction increases so rapidly as the sun approaches the horizon that its lower limb is lifted more than the upper, distorting the sun's disk noticeably.

Related: How to observe the sun safely (and what to look for)

Not as dark as it seems

Certain astronomical myths die hard. One of these is that the entire Arctic region experiences six months of daylight and six months of darkness. Often, "night" is simply considered to be when the sun is beneath the horizon, as if twilight didn't exist.

This fallacy is repeated in innumerable geography textbooks, as well as travel articles and guides. But twilight illuminates the sky to some extent whenever the sun's upper rim is less than 18 degrees below the horizon. (Your clenched fist held at arm's length covers about 10 degrees of sky.) This marks the limit of astronomical twilight, when the sky is indeed totally dark from horizon to horizon.

There are two other types of twilight. Civil (bright) twilight exists when the sun is less than 6 degrees beneath the horizon. It is loosely defined as when most outdoor daytime activities can continue after sunset. Some daily newspapers provide a time when you should turn on your car's headlights. That time usually corresponds to the end of civil twilight.

So, even at the North Pole, while the sun disappears from view for six months beginning on Sept. 25, stating that "total darkness" immediately sets in is hardly the case! In fact, civil twilight does not end there until Oct. 8.

When the sun drops down to 12 degrees below the horizon, it marks the end of nautical twilight, when a sea horizon becomes difficult to discern. In fact, at the end of nautical twilight, most people will regard night as having begun. At the North Pole we have to wait until Oct. 25 for nautical twilight to end.

Finally, astronomical twilight — when the sky indeed becomes completely dark — ends on Nov. 13. It then remains perpetually dark at the North Pole until Jan. 29, when the twilight cycles begin anew. So, at the North Pole, the duration of 24-hour darkness lasts almost 11 weeks, not six months.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.