Top 10 best (or worst) terms in astronomy and physics

They range from totally normal to "Tom Hanks."

Modern astronomy and physics stretch back centuries, so naturally, they've accumulated a lot of interesting names for objects, ideas and phenomena.

And let's face it: Some are downright strange.

From odd choices for the names of astronomical bodies to hard-to-pronounce physics terms, sometimes the words we use in astronomy and physics can be off-putting or come with problematic historical backgrounds.

Here is a list of my favorite ones.

Related: Astronomy: Everything you need to know

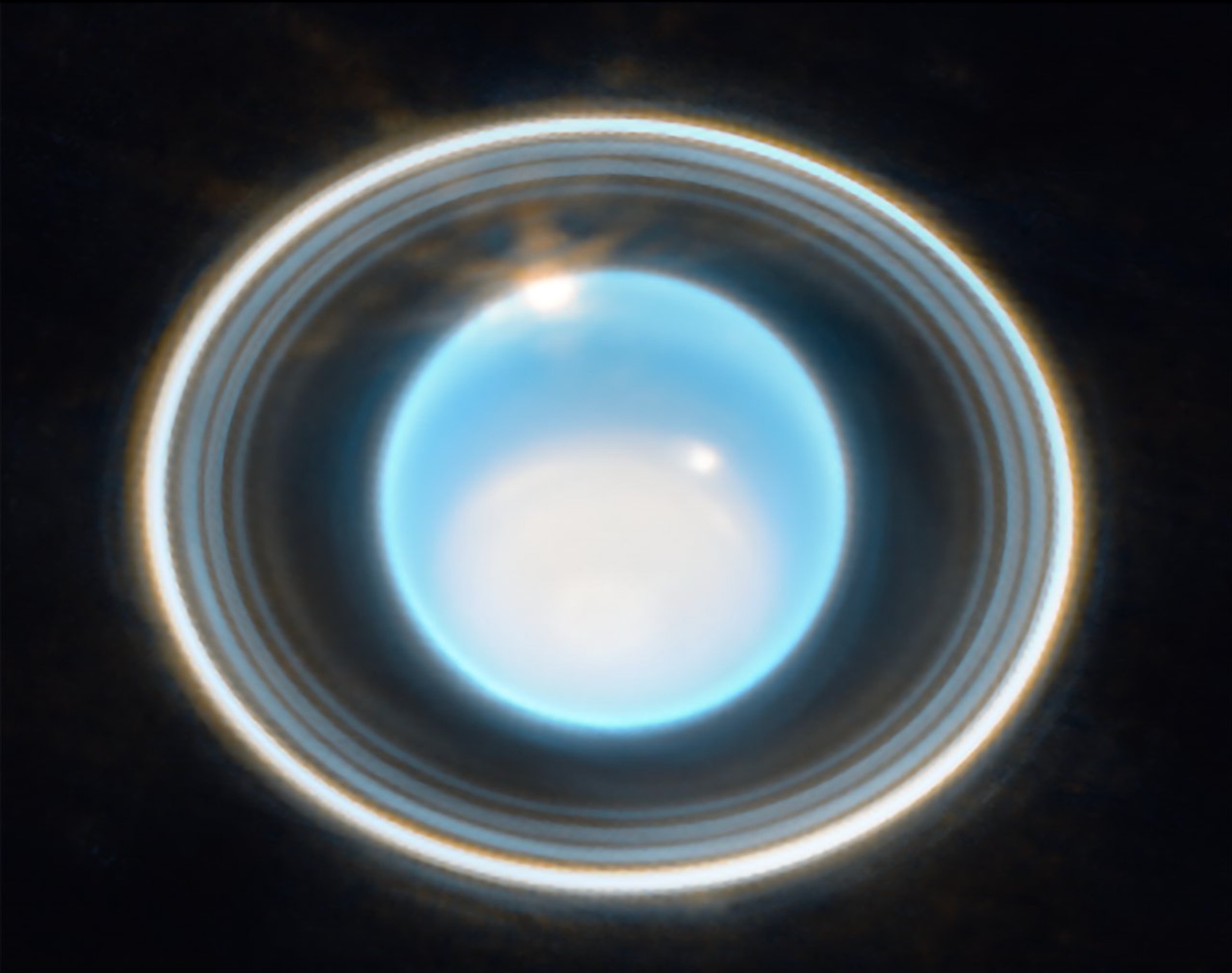

10. Uranus

In 1781, astronomer William Herschel discovered a new planet beyond the orbit of Saturn. When his friend prompted him to do the astronomical community a favor and suggest a name, he proposed "Georgium Sidus," which is Latin for "George's Star," in honor of King George III, the king of England at the time (and Herschel's financial patron). Another prominent astronomer, Johann Bode, suggested "Uranus," which fit with the mythological theme of the other planetary names.

Oddly, while the other planets are named after Roman gods, Bode's suggestion of "Uranus" is really the Latin translation of the Greek god, not the name of the Roman god himself. Historians aren't sure if Bode knew this. Regardless, generations of kids have him to thank for countless jokes about Uranus — which, by the way, is pronounced "YOOR'-un-us."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

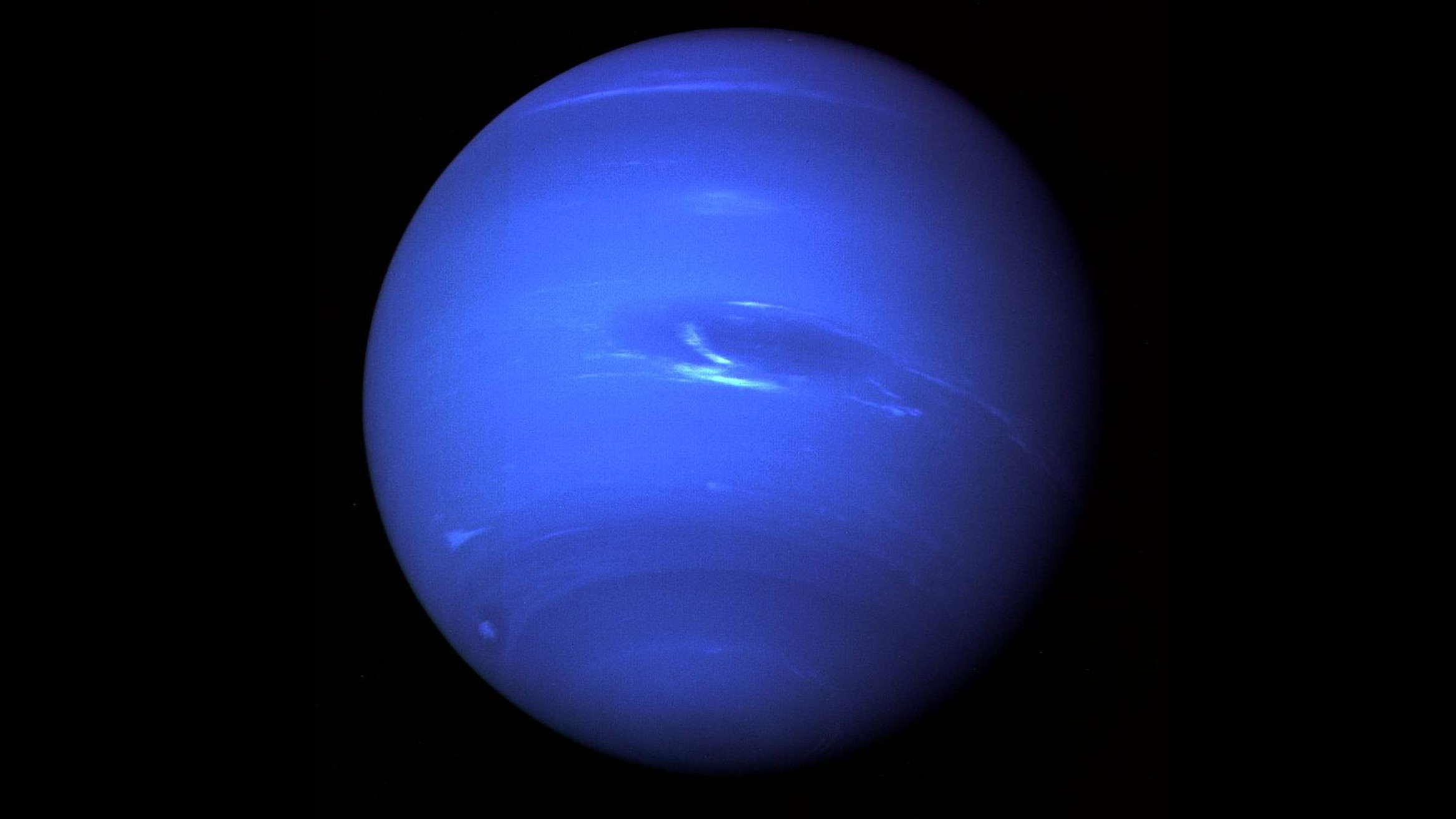

9. Neptune

In 1846, French astronomer Urbain Le Verrier predicted the existence of yet another planet more distant than Uranus. Once it was discovered, the community looked to Le Verrier for a name. At first, he suggested "Neptune" (which was also a contender for what would become Uranus). But he quickly changed his mind and offered the totally modest suggestion of … Leverrier.

The only organization to support this idea was the Paris Observatory, which retconned history and started calling Uranus "Herschel" as a way to legitimize Le Verrier's bold suggestion. Nobody else in the world cared much for that, so his original suggestion of Neptune stuck.

Related: Night sky, Aug. 2023: What you can see tonight [maps]

8. Tomhanks

The International Astronomical Union (IAU), headquartered in Paris, maintains sole naming authority for all astronomical objects and features. According to the IAU's guidelines, you must adhere to certain restrictions in naming most deep-sky objects — basically, you have to give any new discovery a boring category number. The exception is asteroids.

If you spot a new asteroid, the IAU will generally accept your suggested name. So when University of Arizona astronomer Joseph L. Montani discovered a new asteroid in 1996, he decided to name it after one of his favorite actors, Tom Hanks. Because the IAU mandates that asteroids have only a single name, however, the space rock's official designation is 12818 Tomhanks.

Related: How are stars named?

7. St. Catherine's Wheel

This distant galaxy has the proper designation of Messier 99, after a catalog created in 1774 by French astronomer Charles Messier. But the large spiral galaxy, located in the Virgo Cluster, has a more sinister nickname: St. Catherine's Wheel.

The galaxy has roughly three times more active star formation than a typical galaxy, so through a telescope, it appears as a fantastic wheel of stars, reminiscent of a torture wheel used to kill St. Catherine, an 18-year-old martyr, in A.D. 305.

6. The Fetus Nebula

This planetary nebula is the remains of a sunlike star; all that's left are wisps of gas and dust blown out by the powerful winds of the dying star. Its formal name is NGC 7008, but based on its appearance, the nebula, which sits about 2,800 light-years away, has a much more anatomical name: The Fetus Nebula.

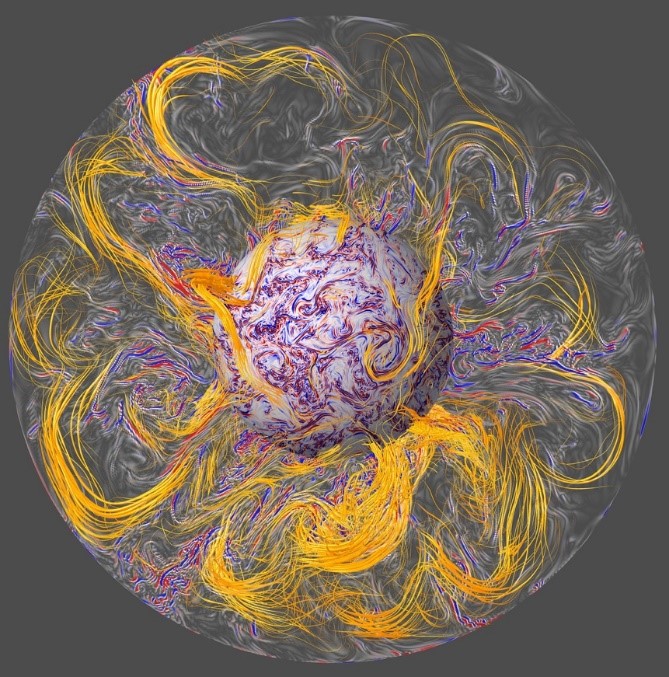

5. Syzygy

If it looks like a cat just walked over someone's keyboard, it's probably an astronomical term. Case in point: syzygy (pronounced SIZ'-a-jee), which comes from the Greek word for "union." This is the astronomical term for when three or more celestial objects find themselves in a straight line. Perhaps the most famous example of a syzygy is a total solar eclipse, when the sun, the moon and Earth all line up.

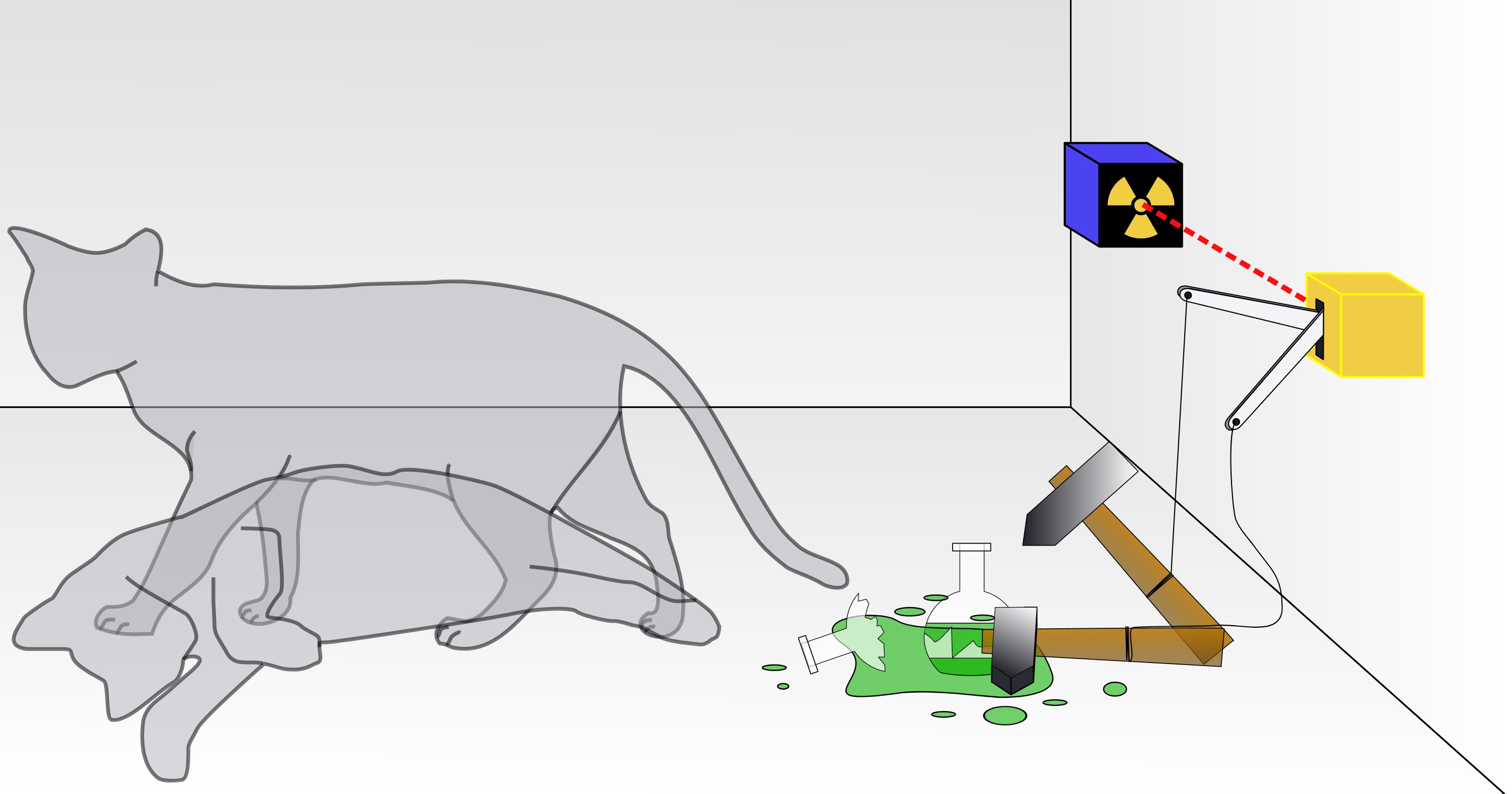

4. Gedankenexperiment

The practice of physics requires an enormous amount of creative brainpower. The epitome of this is the "gedankenexperiment," which is German for "thought experiment." Physicists constantly imagine hypothetical scenarios and use those to think through the logical consequences of a hypothesis, and the practice has become so cemented as a part of physics training that it got its own name. Perhaps the most famous gedankenexperiment is attributed to Albert Einstein, who imagined what it would be like to ride alongside a beam of light. His insights would eventually lead to the theory of special relativity.

3. Quarks

When physicist Murray Gell-Mann cracked the inner workings of the strong nuclear force, he discovered that his theory required three new particles of name. Struggling to find a suitable moniker, he came upon a quote from James Joyce's 1939 novel "Finnegans Wake": "Three quarks for Muster Mark!" The name seemed new and interesting, so Gell-Mann used it for the subatomic particle. Later physicists discovered that there were actually six quarks, but by then, the name had stuck.

2. Jerk

Yeah, this word describes an unsavory person — but it's also a strange term for a particular measurement of movement. If you change your position, you have velocity. If you change your velocity, you have acceleration. And if you change your acceleration, you have jerk.

The term doesn't come about frequently, because for almost all applications, all we need to care about are velocity and acceleration. But it's there in case you need it.

1. Hand-waving

If you've ever encountered an argument that seemed to skip a few critical steps, you've seen an example of hand-waving. It's an endearing term in physics, because eventually, everyone does it at one time or another. Not every argument or line of thought is supported by the most rigorous steps, so sometimes, you just have to "wave your hands" and hope for the best.

Paul M. Sutter is a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University, host of Ask a Spaceman, and author of How to Die in Space.