How are stars named?

Reference article: How stars are named in the era of exoplanets.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

There are many thousands of stars visible from Earth, and hundreds of billions of stars in our Milky Way galaxy alone. When skywatchers and astronomers want to observe or study these sparkling objects in the sky, it helps if we all refer to them with the same name.

Technically, anyone is free to give any name to any star. But if a name for an individual star is going to be used consistently by professional astronomers, it has to be approved by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a 100-year-old professional organization of more than 10,000 astronomers from all over the world.

In 2016, Eric Mamajek, an astronomer based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, initiated the IAU's Working Group on Star Names. The impetus for creating the group was the IAU's first contest inviting the general public to name a selection of exoplanets and their host stars, held in 2015, Mamjek told Space.com.

Article continues belowThe entries that came in for this contest highlighted a problem: duplication of names. Several of the most popular names in the first "NameExoWorlds" contest had already been given to asteroids and small moons of Jupiter and Saturn, so the contest organizers ended up substituting related names from the same mythologies and traditions.

When a star is to be named, Mamajek said, "shouldn't historical or cultural names with centuries of use by generations of skywatchers be given preference over a new name, which might be devised on a lark by someone who may have never seen the star?"

Related: From 'Abol' to 'Yvaga': 224 stars and planets get new names for year of indigenous languages

The IAU tightened up the naming rules in its second "NameExoWorlds" contest in 2019. And while they were at it, they came to realize that there was no accepted list of star names that would be off-limits for recycling in the future. "I thought, what's to keep you from naming a planet Vega?" Mamajek said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The IAU promoted the ExoWorlds idea but needed expertise on what stars had already been named," Mamajek said. "Our group has historians and experts on cultural astronomy."

The Working Group on Star Names focused on two tasks: Deciding on standardized versions of star names already in use and, later, developing guidelines for selecting and assigning new star names in the era of exoplanet discovery. So far, the Working Group (a team of 19 astronomers and historians from 11 countries) has approved names for over 300 bright stars, and it continues to search the world's literature for more.

- Related: See the stars yourself with the best telescopes available

Naming stars, then and now

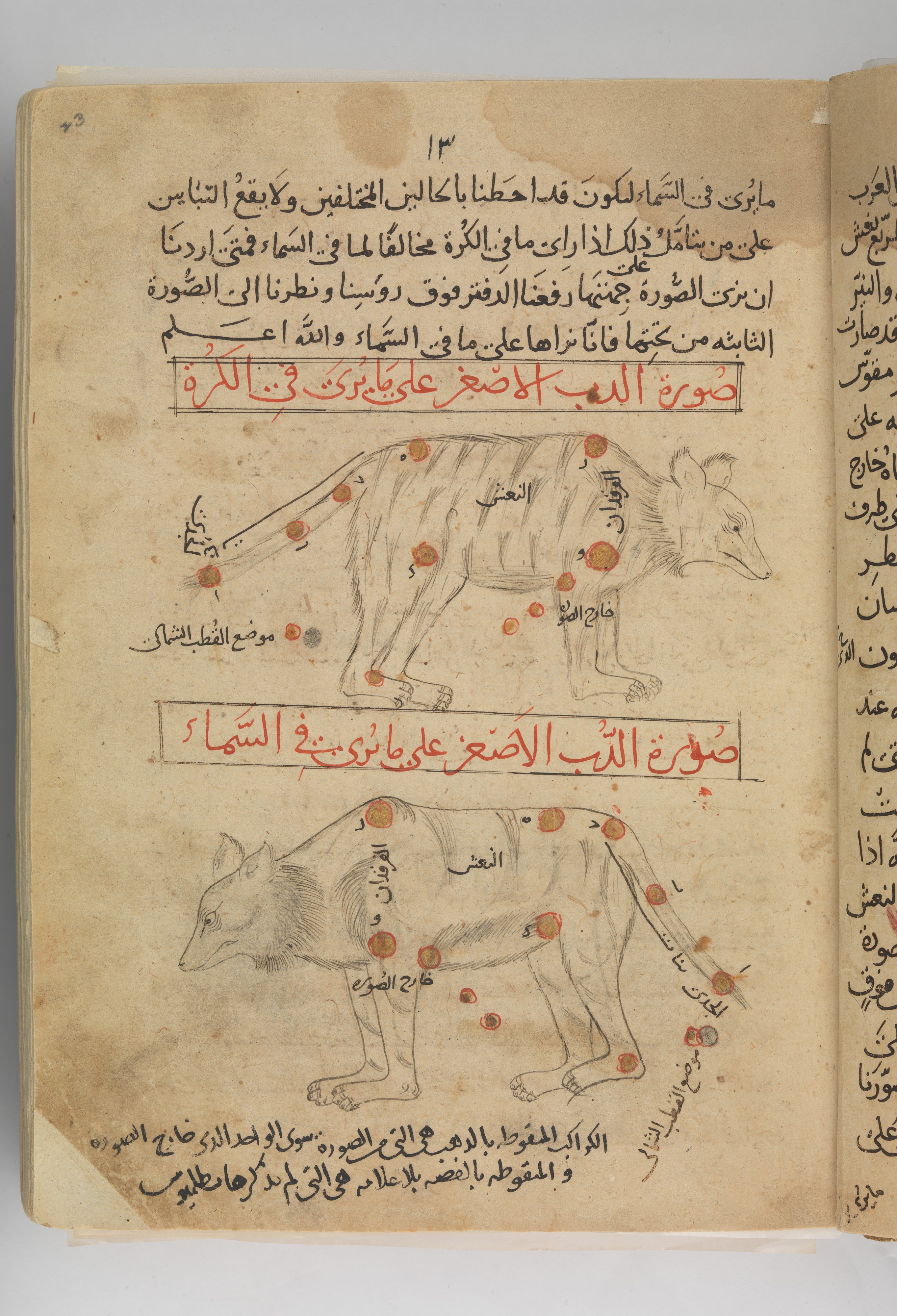

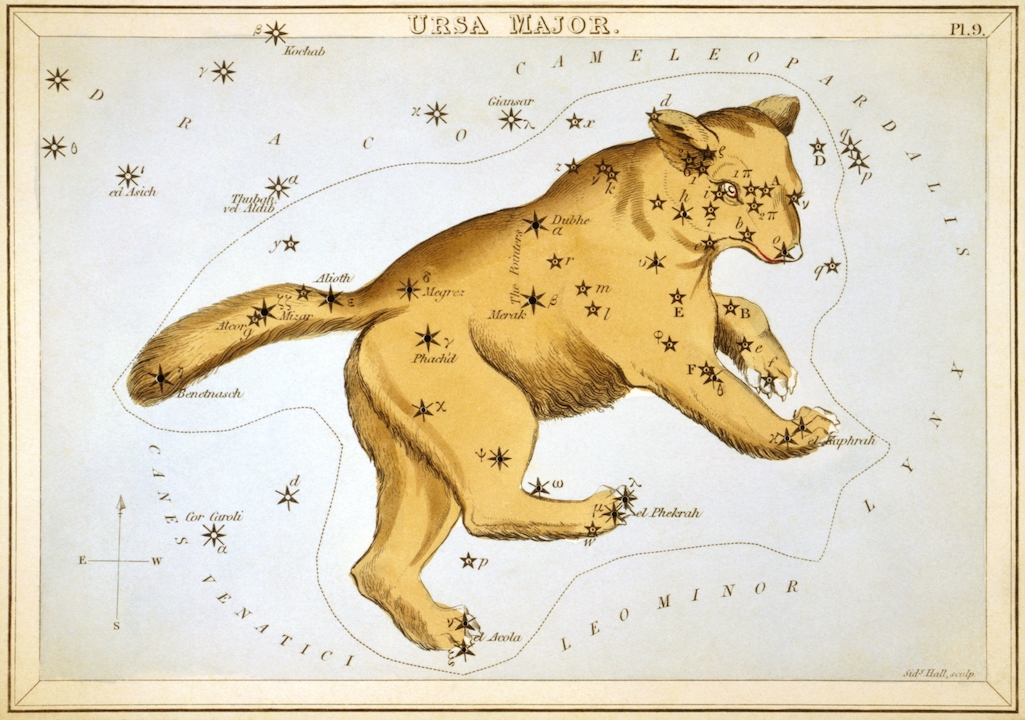

Existing star names from Arabic, ancient Greek and other traditions had been offered in various forms on star charts and globes and in a few old books, such as "Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning," which was compiled in 1899 by Richard Hinckley Allen, a Wisconsin-born businessman and amateur astronomer. (The book was reprinted by Dover Publications in 1963).

An expert view of the Arabic names became widely available in English with "A Dictionary of Modern Star Names" (Sky Publishing, 2006), by Paul Kunitzsch and Tim Smart, and based on Kunitzsch's decades of research as a professor of Arabic studies.

Related: The brightest stars in the sky: A starry countdown

Names for a few of the brightest stars, such as Sirius and Vega, were already widely used and understood by astronomers. But star names beyond the most famous appeared in various forms in different books and articles. As an example, the Working Group cited the brightest star in the constellation Cepheus, which has been called Alderanin, Alderamin, Alderaimin, Alderaimim and Al'deramin.

"This was very different from the IAU's treatment over the past century of (solar system) planets, planetary satellites, asteroids, planetary surface features and the constellations — all of which have official, unique, alphabetical IAU proper names," the Working Group noted in its 2018 report.

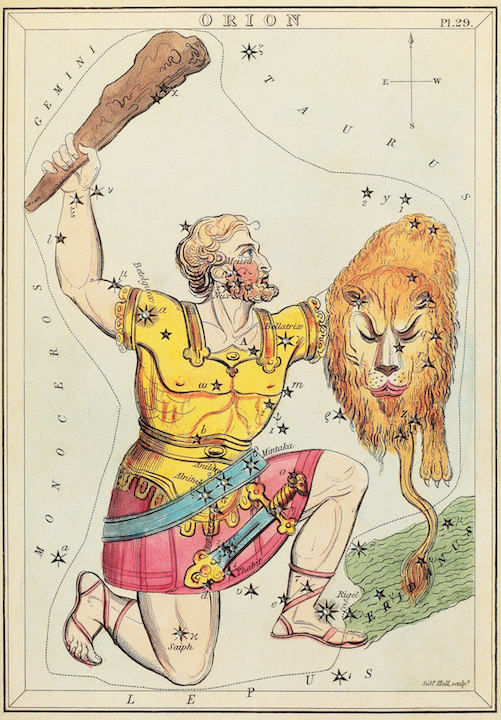

Related: How the night sky constellations got their names

Until recently, problems with star names didn't matter much to professional astronomers, who usually refer to stars by designations rather than names. A designation is some combination of letters and numbers that refers to only one star in a list.

"Designations make sense," Mamajek said. "For example, [the bright star] Fomalhaut is HD 216956," an entry in the Henry Draper Catalogue, a list of more than 350,000 stars that's widely used by professional astronomers.

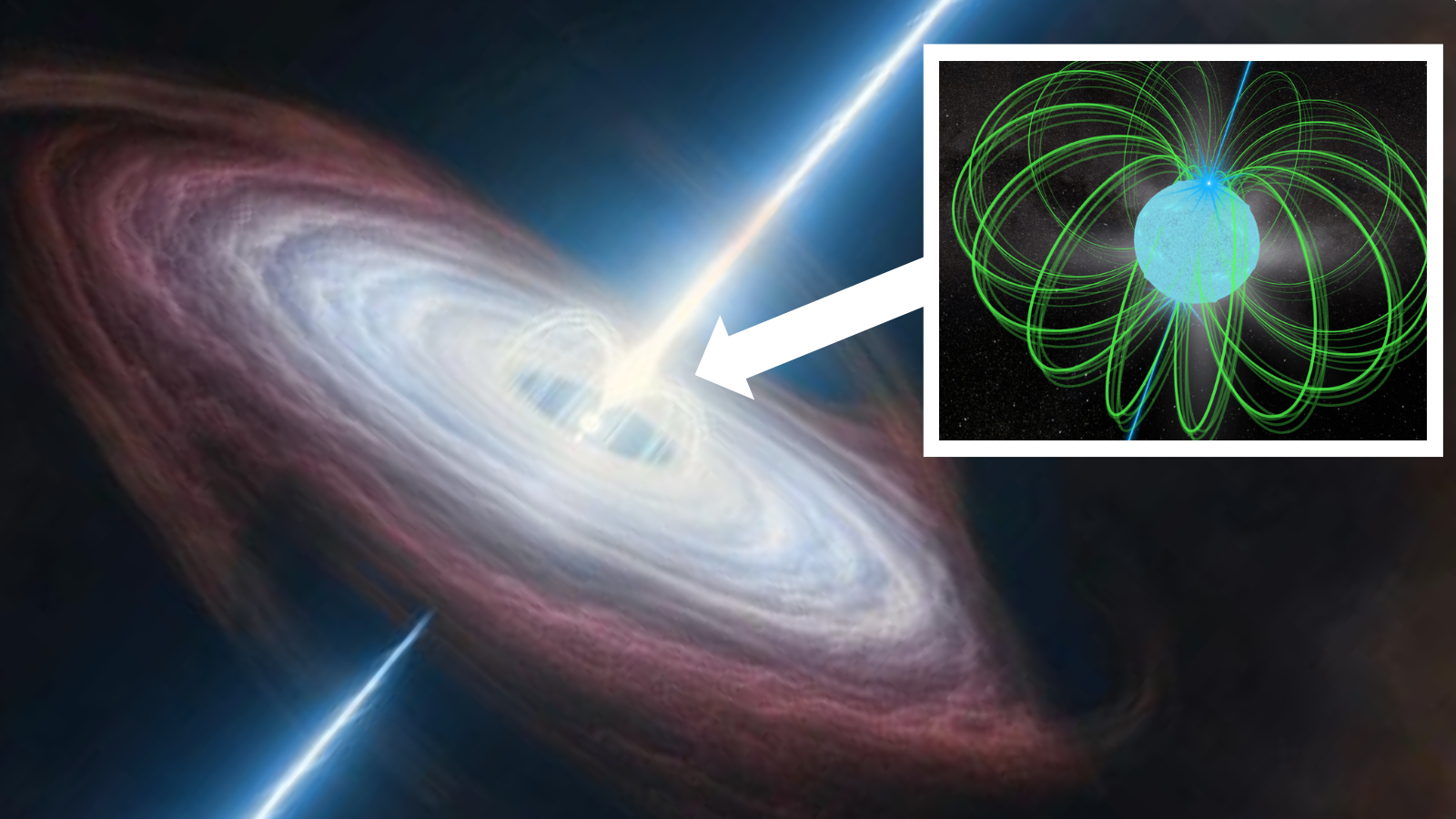

But "numbers are very forgettable," Mamajek said. "Stars are turning from pinpricks of light into destinations," as more exoplanets are discovered. So, proper names are becoming important.

From the beginning, the IAU was clear on two points: They would not endorse or recognize the buying or selling of star names, and they would not assign names as favors in response to requests.

"We get emails every few weeks asking us to name a star after someone's sweetheart," Mamajek said. "That's not what we do."

The working group's 2018 report states: "Names that preserve world heritage (astronomical heritage, cultural heritage, and natural heritage) are strongly encouraged. Common and cultural star names are to be preferred over new names."

The Working Group announced its first batch of approved star names, covering 227 bright stars, in 2016. The list recognized the names Proxima Centauri, Rigil Kentaurus (the ancient name for the star Alpha Centauri), and dozens of star names used by navigators. It settled, once and for all, modern spellings of ancient names such as Alderamin and Fomalhaut, whose name had been spelled more than 30 different ways.

These names would not replace designations such as HD numbers, but from then on, these stars could be referenced by name without confusion, and their names would not be inadvertently reused for asteroids, moons or exoplanet systems. Did you know that ancient cultures lend titles to 86 suns.

The Working Group realized that they could do even more. The star-naming project "presented a unique opportunity to start to formally recognize some of the wide variety of celestial nomenclature from cultures around the world, which had previously been largely ignored or simply excluded from previous star name catalogues in common use," the group's 2018 progress report noted.

"Preserving star names points you to the whole human experience," Mamajek said. "Pick up a celestial globe and point at any named star — there's a whole story there."

After a search of international literature on the history and culture of astronomy, the group released a second batch of 86 names in 2017, drawing from Australian Aboriginal, Chinese, Coptic, Hindu, Mayan, Polynesian and South African traditions.

- Related: Best cameras for astrophotography

- Related: Best lenses for astrophotography

Naming new stars and exoplanets

With time-honored names now being settled for bright stars, completely new star names will most likely go to exoplanet systems. "Most exoworld stars are fainter than naked-eye visibility, so they haven't been named," Mamajek said.

The IAU ran a second "NameExoWorlds" contest in 2019 that generated names from 112 participating countries. Submitted names honored rivers, mountains, writers, artists and significant fictional or mythological characters from each country, many in indigenous languages.

The Working Group on Star Names continues to research star names from around the world.

Related: Another day, another exoplanet, and scientists just can't keep up

"We are still trying to get more etymologies for existing star names before the IAU's 2021 general assembly," Mamajek said. "We have a vast collection of sources. Most of the low-hanging fruit has been found; scans of old books, easily Googleable facts — we already have that."

The Working Group's web page asks for help in finding ancient celestial names from cultures not yet well represented in the approved lists — particularly those from the Americas, Africa, Australia, Polynesia and Asia outside of China and Japan.

"I'm looking at this for the long haul," Mamajek said. "We are going to be looking at the same stars and planets far into the future. We are discovering new worlds. In the future, we won't refer to [the exoplanets] TRAPPIST-1 b, c, and d by letters. We'll use names."

Additional resources:

- Check out the IAU's introduction to star naming.

- Here are the IAU's first and second batches of exoworld names.

- Learn more about astronomical heritage from UNESCO's Portal to the Heritage of Astronomy.

Steve is a former contributor to Space.com in the coverage areas of stars, exoplanets, and constellations. He's an author, podcaster, and retired Planetarium Director at Rochester Museum & Science Center where he was employed for 28 years and responsible for content and scheduling of the venue's Planetarium astronomy shows. Other duties included adapting still and moving images, music and sound, narrating shows, and leading selection and scheduling of all film and laser shows. His book, Sky to Space: Astronomy Beyond the Basics with Comparisons, Ratios and Proportions was published in 2017.