What are star charts?

Reference article: Facts about star charts and how to use them.

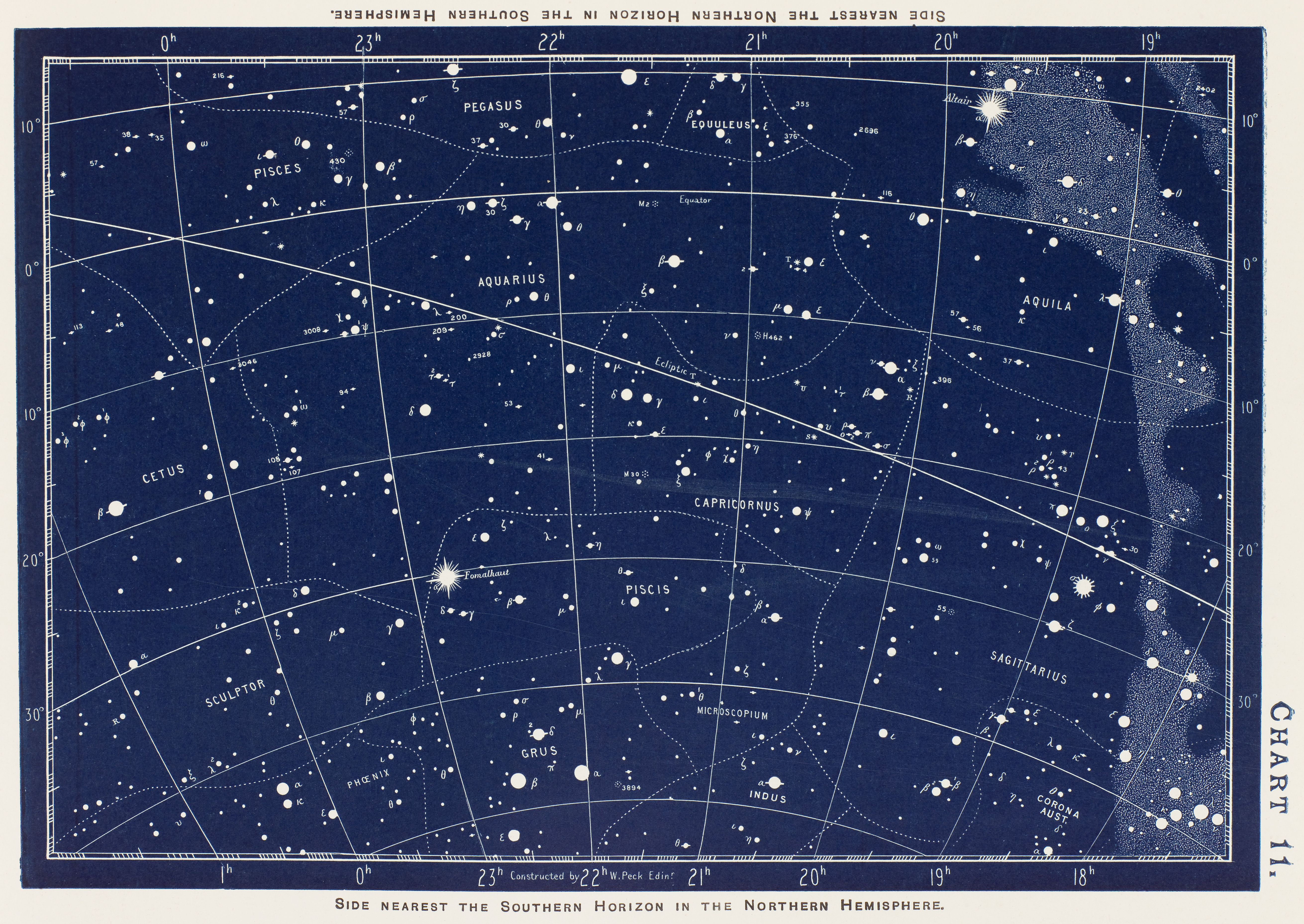

With their unique and slightly mysterious look, star charts attempt to capture what we see and what we know about the night sky. Styles have evolved over time, from elaborate decorated maps of centuries ago to the crisp computer-generated charts of today.

Related: Best telescopes for the money — 2020 reviews and guide

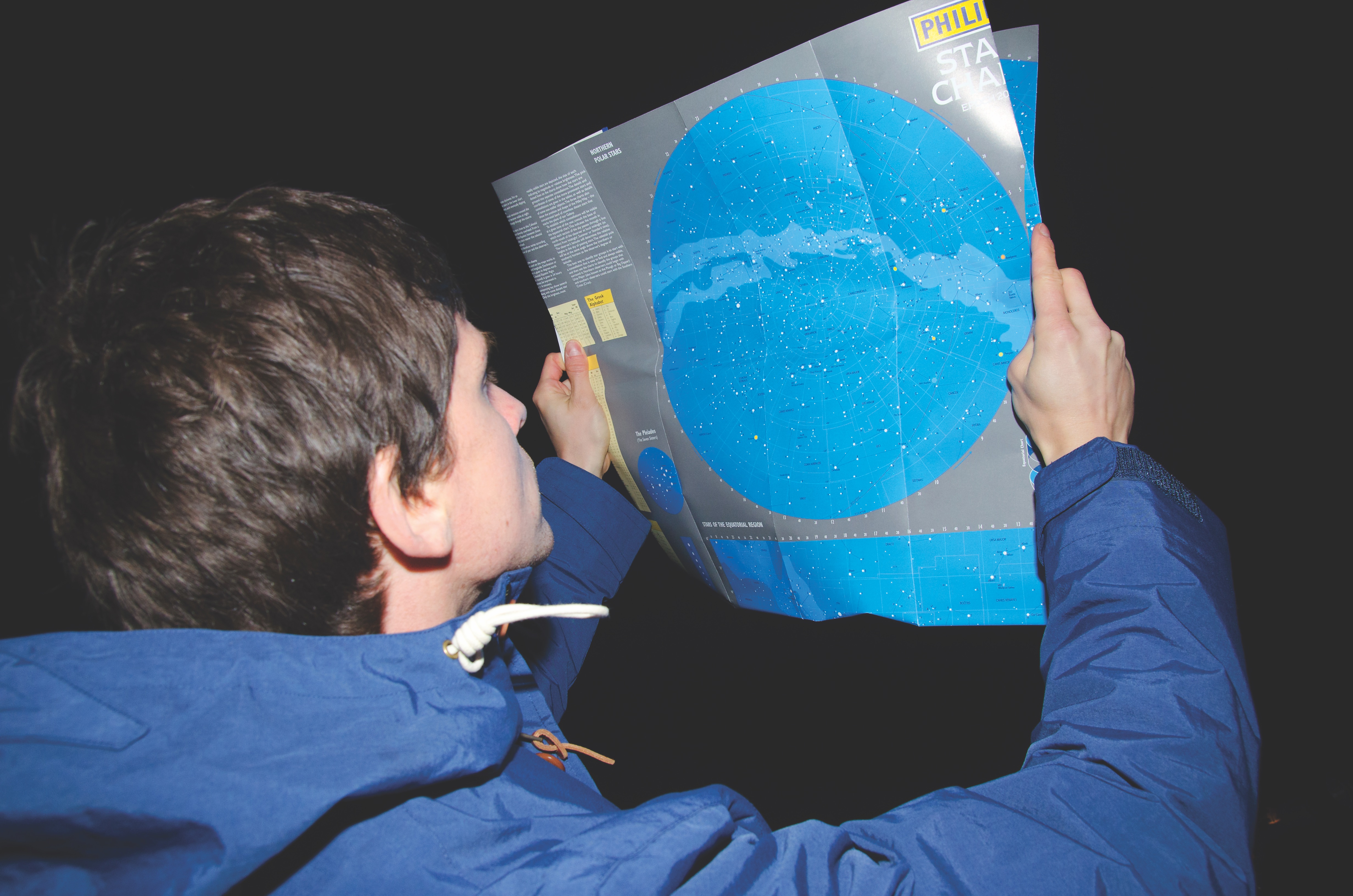

How to use a star chart

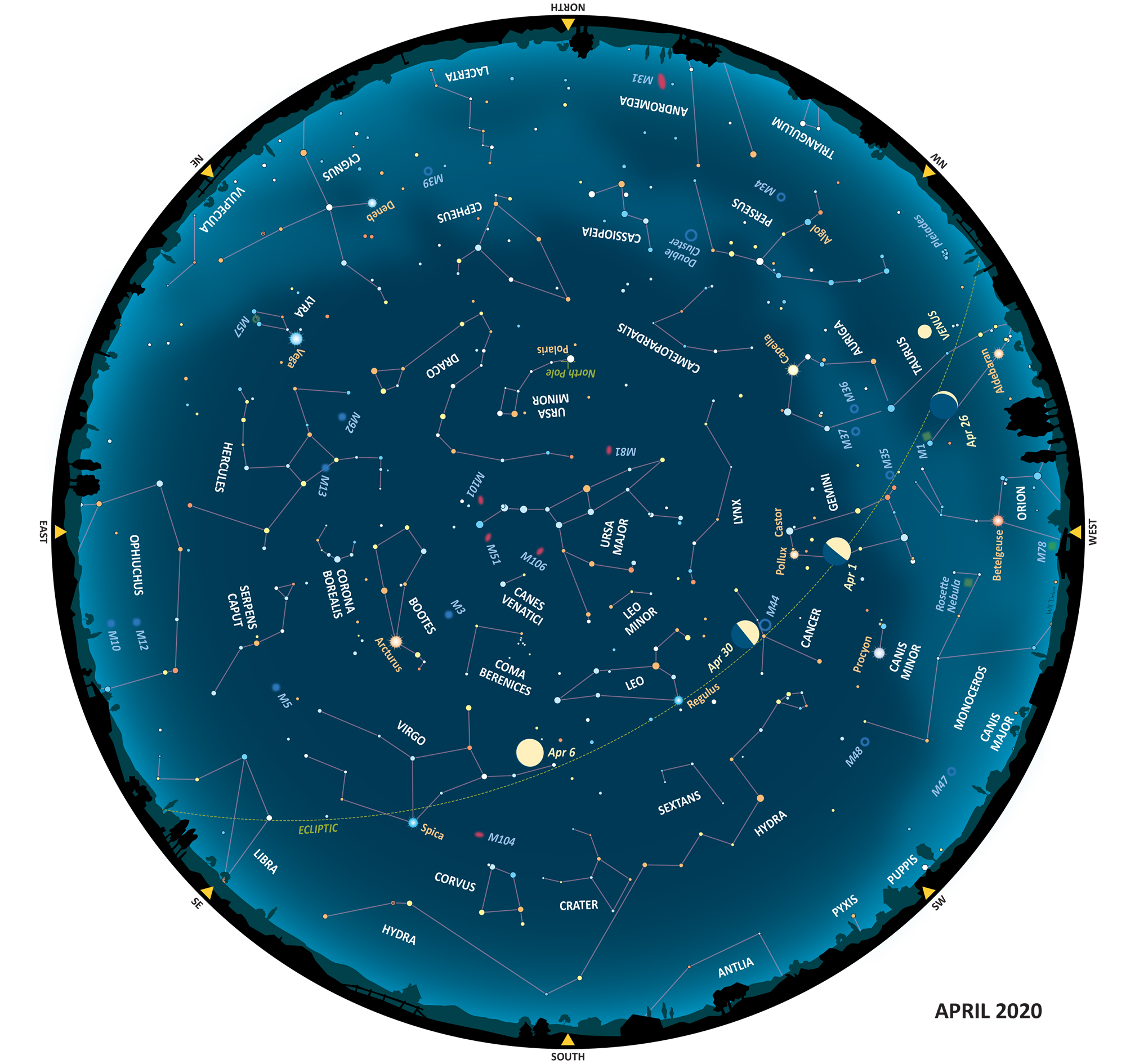

A monthly star chart from a magazine, newspaper or museum is likely to take the form of a circular area peppered with dots representing stars arranged as they appear in the sky. The center of the chart shows stars that are directly overhead. The outer rim represents the horizon, labeled with the directions north, south, east and west.

To match the sky, the chart must be held overhead, with the chart's north marker pointing north. And it has to be a chart that was made for the month you're in. There will usually be a note with the chart explaining the time of night it matches best -— for example, later in the evening at the beginning of the month and earlier in the evening at the end of the month.

Related: How to choose binoculars for astronomy and skywatching

Also popular are star-finder wheels, or planispheres, that can be adjusted for any date and time. These are two-layered devices, with a large full-circle chart under a cover that has an oval window. The background chart includes all the stars visible throughout the year, but the window reveals only those stars that are above the horizon at a particular date and time. You rotate the background chart around a pivot, watching numbers on the edges until you have the current date lined up with the current time. Then the window shows those stars you can expect to see.

Elements of a star chart

Whatever the format, star-chart makers have a number of choices:

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

- Dark or white background? A black or dark blue background, with white dots for stars, looks more natural. But a white background with black dots for stars is easier to print and allows the user to write in notes of their own.

- Lines or no lines? Guide lines can connect the stars into shapes that lead the eye from star to star. The Big Dipper, the Great Square of Pegasus, the three stars of Orion's Belt and other shapes are traditional and frequently used. But you are free to invent different stick figures if they help you find your way.

- How big and how small to make star dots? Big dots suggest brighter stars, small dots fainter ones. It's an art to come up with a graded set of star dots that gives an accurate impression of the range of brightnesses in the real sky.

- Constellation figures or none? Some star charts, particularly those from the 1600s to early 1800s like those you might find in art books or as vintage decorative items, depict a wild party of mythological figures, from Andromeda to Vulpecula, swimming around the sky. Some are memorable, but many are baffling. For example, the form of Orion is not hard to imagine in the constellation’s pattern of two shoulder stars, three belt stars, and two stars for feet or knees. But trying to make Ursa Major, the Greater Bear, out of the Big Dipper and surrounding stars, can be frustrating.

In a popular astronomy book published in 1842, "The Sidereal Heaven and Other Subjects Connected with Astronomy" (Edward C. Biddle, 1842), author Thomas Dick describes mythological constellation drawings as "grotesque and incongruous figures … mean, ridiculous and imaginary objects." Starting in the 20th century, star charts usually omitted mythological figures in favor of stick figures, or the straight-line boundaries between constellations that were agreed on by the International Astronomical Union in 1930.

- Planets or not? Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn look like bright stars when viewed from Earth. They can appear anywhere in a band wrapping all the way around the sky called the zodiac. If a star chart is made for a particular month in a particular year, it may show the planets' locations for that month.

Related: 10 must-see skywatching events to look for in 2020

Full-circle charts inevitably stretch constellations near the edges, just as Earth maps stretch remote continents. (For example, rectangular world maps using the Mercator projection make Antarctica and Greenland look much larger than they are.)

To reduce distortion, celestial cartographers can make charts of sections of the sky. Norton's Star Atlas, which has gone through 18 editions since 1910, divided the sky into gores, like segments of an orange, each segment covering about one-fifth of the sky with little distortion. Star atlases for serious amateur astronomers include big charts that zoom in on even smaller pieces of sky.

Star charts for navigation

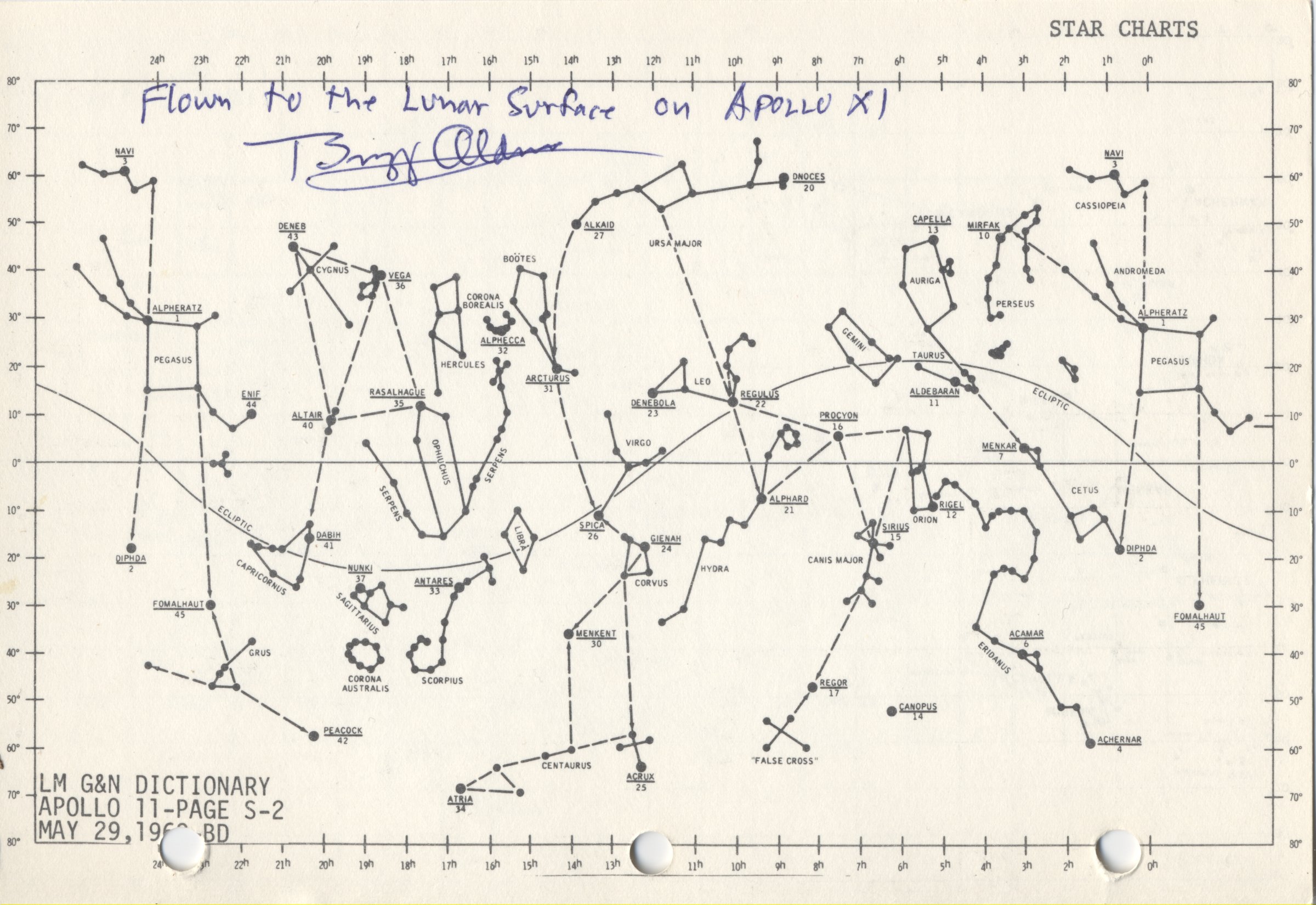

Star charts also serve as serious professional tools used by navigators at sea. If the Global Positioning System satellite infrastructure goes down, a trained navigator or quartermaster can turn to traditional celestial navigation, consulting a no-frills chart that identifies 58 bright navigational stars. The navigator will select one of these stars, measure its direction and its height above the horizon, note the exact time, then run those numbers through a calculation that yields the ship's latitude and longitude.

On the Apollo moon missions, astronauts carried charts identifying bright navigational stars, sighting on them to fine-tune the spacecraft's attitude-control system. In 2018, astronauts on the International Space Station tested star-sighting techniques as a backup procedure for future missions, NASA reported.

Rest assured that if high-tech systems fail, the stars will still be there for those who know how to use them.

Additional resources:

- Explore strange and beautiful illustrated astronomy books from Galileo's time in an online exhibit from the University of Oklahoma Libraries.

- Learn about the ancient Chinese view of the stars from the British Library.

- Read a discussion of how Polynesian celestial navigation was portrayed in a Disney movie.

- Pay a virtual visit to Chicago's Adler Planetarium to view their collection of historical star charts and other astronomical instruments.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Steve is a former contributor to Space.com in the coverage areas of stars, exoplanets, and constellations. He's an author, podcaster, and retired Planetarium Director at Rochester Museum & Science Center where he was employed for 28 years and responsible for content and scheduling of the venue's Planetarium astronomy shows. Other duties included adapting still and moving images, music and sound, narrating shows, and leading selection and scheduling of all film and laser shows. His book, Sky to Space: Astronomy Beyond the Basics with Comparisons, Ratios and Proportions was published in 2017.