A Visit to Watery Super-Earth Alien Planet K2-18 b Would Be Super-Strange

The alien planet K2-18 b would be a truly exotic vacation destination.

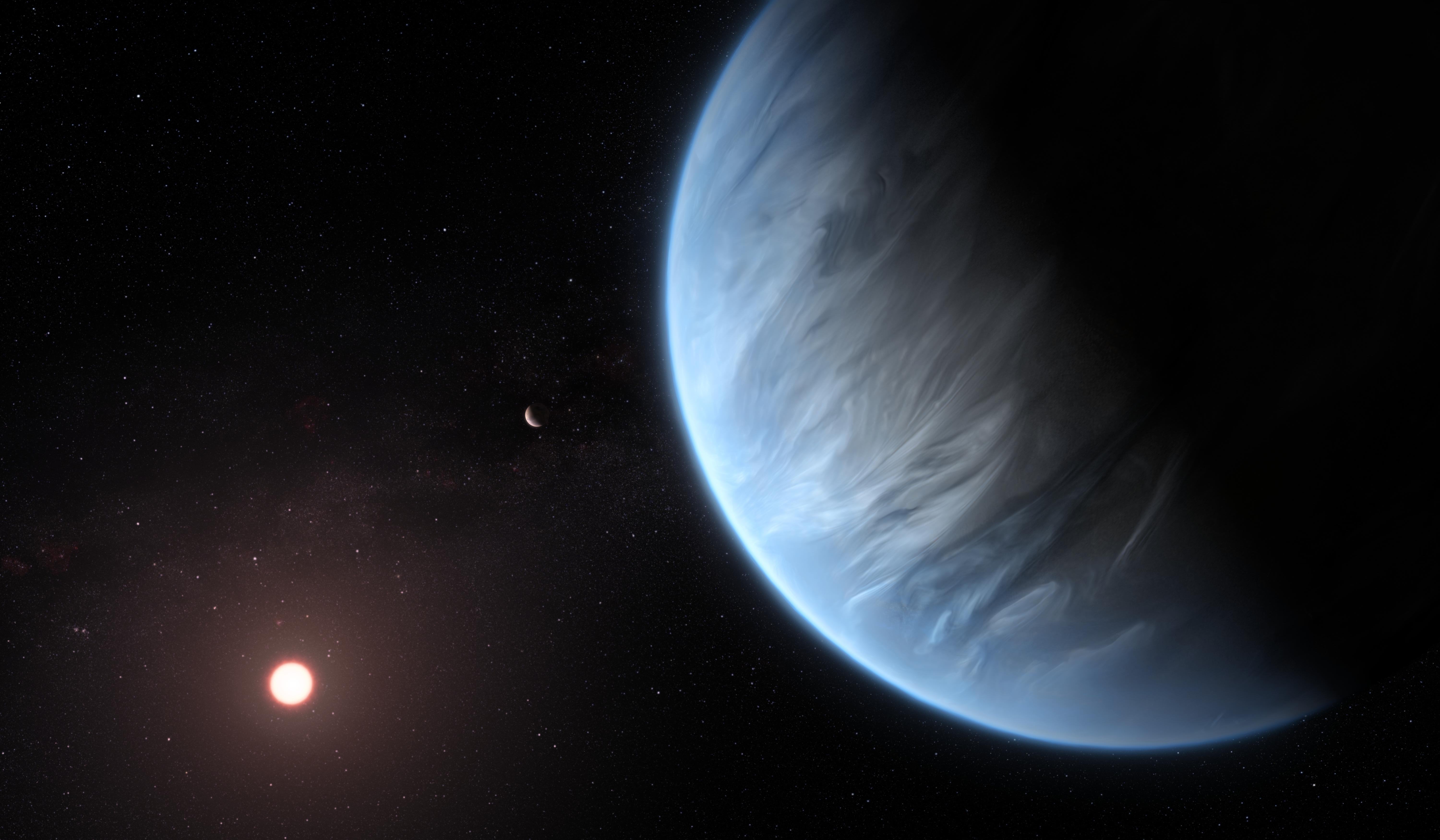

Two research teams just announced the detection of water vapor in the air of K2-18 b, a "super-Earth" that lies about 110 light-years from our planet. This is a landmark discovery, because the alien world is potentially habitable, apparently orbiting its star at the right distance for liquid water to exist on the planetary surface.

But this doesn't mean that K2-18 b is Earth-like; in fact, the two worlds are quite different. K2-18 b is about 2.3 times wider than Earth and eight times more massive, for example, and it orbits a red dwarf, a star much smaller and dimmer than our own sun.

Video: Water Vapor Discovery in Exoplanet K2-18 b's Atmosphere

Related: The Strangest Alien Planets

So, what would a trip to K2-18 b be like? Very long, for starters — it would take more than a million years to get there using traditional rocket propulsion. But let's put matters of practicality aside. What would you see on the surface of this world? What would you experience?

It's tough to say, unfortunately. For starters, K2-18 b, which was discovered in 2015, orbits relatively close to its host star, completing one lap every 33 Earth days. So, the planet could be tidally locked, always showing one face to the red dwarf, just as Earth's moon always shows us its near side. If that's the case, then K2-18 b would have a day side and a night side, with a strip of permanent twilight separating the two.

But we don't know if that's the case, and the uncertainty continues from there.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

One of the research teams, led by Angelos Tsiaras of University College London's Centre for Space Exochemistry Data (CSED), determined that water vapor makes up between 0.01% and 50% of K2-18 b's atmosphere. With such a big range, it's tough to characterize the exoplanet; it could be completely flooded, for instance, or a world with lakes and oceans but lots of exposed land, study team members said.

The other research group, led by Björn Benneke of the Institute for Research on Exoplanets at the Université de Montréal, posited another scenario. These scientists suggested that K2-18 b consists of a planetary core surrounded by a huge, hydrogen-dominated atmosphere that contains mere smidges of water vapor. Such a world wouldn't have a surface, at least not the kind we're used to here on Earth.

Tsiaras and his colleagues published their results yesterday (Sept. 11) in the journal Nature Astronomy. Benneke's team has posted its paper to the online preprint site arXiv.org; the study has not yet been peer-reviewed.

The planet's temperature is also uncertain. Tsiaras' team estimated a surface temperature of between minus 100 and 116 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 73 to 47 degrees Celsius). That means the surface could, on average, be colder than Antarctica or hotter than Earth's most blistering deserts.

K2-18 b's gravitational pull is better understood, because we know the planet's mass and diameter. If most of the exoplanet is solid rock and ice, a visitor to the world's surface would feel 37% heavier than he or she feels on Earth. (K2-18 b's higher mass is mostly offset by its greater size in this regard, because the gravitational force decreases with the square of the distance from a planet's center.)

The picture would be more complicated if K2-18 b is mostly atmosphere, as envisioned by Benneke's team. In that case, the gravitational pull you'd feel would depend on the size of the planet's core. But the force of that pull wouldn't really matter from your perspective; the massive atmosphere would generate such high pressures that you'd be squished wherever you tried to stand.

But if you could survive, and if you could see through that atmosphere, you'd be treated to some memorable vistas.

During a teleconference with reporters Tuesday (Sept. 10), Tsiaras pointed out that K2-18 b has a sibling that orbits closer to the host star. From the surface of K2-18 b, this other planet might look like Venus does in Earth's sky, Tsiaras said.

And then there's the star itself, which would look quite different from our own sun.

"You would see a red star rather than an orange-yellow one," Ingo Waldmann of CSED, a member of Tsiaras' team, said during the telecon.

Red dwarfs tend to be more active than sunlike stars, more frequently unleashing powerful flares. K2-18 b's parent star is quiescent by red dwarf standards, Waldmann said, but the star may still bathe the planet in higher quantities of damaging ultraviolet radiation than we're used to.

"For life on Earth, that would be bad — we'd all get cancer relatively quickly," Waldmann said. "But, you know, life there may have evolved differently. So, it's hard to tell."

- 10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life

- How Habitable Zones for Alien Planets and Stars Work (Infographic)

- Biodiversity on Some Alien Planets May Dwarf That of Earth

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.