The Water Vapor Find on 'Habitable' Exoplanet K2-18 b Is Exciting — But It's No Earth Twin

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Astronomers are finding more and more alien worlds that may be capable of supporting Earth-like life, but none of these exoplanets so far are carbon copies of our home world.

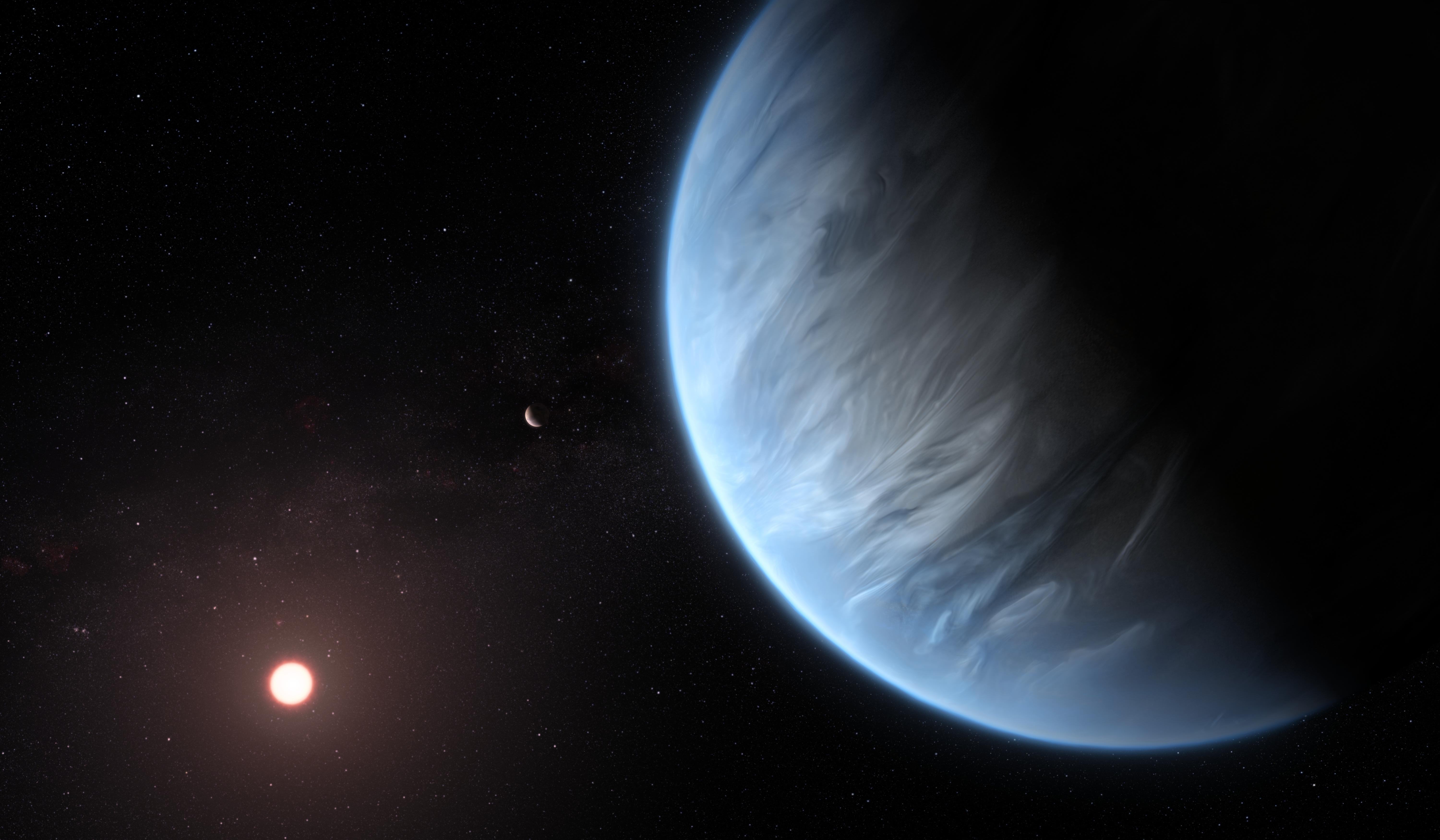

The newest exciting find involves K2-18 b, a planet about 110 light-years from Earth that NASA's Kepler space telescope discovered in 2015.

K2-18 b lies in its parent star's "habitable zone," the range of distances that could support the existence of liquid water on a world's surface. Two teams of scientists announced this week that they've found water vapor in this world's air — a big milestone in the search for alien life.

Related: 10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life

"This is the only planet right now with the correct temperature [for Earth-like life] and water outside the solar system," Angelos Tsiaras of University College London's Centre for Space Exochemistry Data (CSED), the leader of one of the research teams, told reporters during a teleconference Tuesday (Sept. 10).

Tsiaras and his colleagues published their results today (Sept. 11) in the journal Nature Astronomy. The other research team, led by Björn Benneke of the Université de Montréal, posted its paper on the online preprint site arXiv.org Tuesday. The study by Benneke et al. has not yet been peer-reviewed.

Tsiaras and his colleagues stressed that K2-18 b is far from an Earth twin. The exoplanet is eight times more massive than our world, making it a "super-Earth," a type of world that's common throughout the Milky Way galaxy but is not represented in our own solar system.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Then, there's the matter of K2-18 b's star, a red dwarf much smaller and cooler than the sun. Because red dwarfs are so dim, their habitable zones reside much closer in; K2-18 b completes one orbit every 33 Earth days.

The alien planet may therefore be "tidally locked" to its star, always showing the red dwarf the same face, just as Earth's moon only ever shows its near side to us. But this would not be a dealbreaker for the existence of life.

"A tidally locked planet can also be habitable," said Ingo Waldmann of CSED, a member of Tsiaras' team. Modeling studies suggest that "the energy from the dayside can be quite equally distributed to the nightside," Waldmann added.

Tidally locked or not, such a world would be decidedly unlike Earth. Indeed, K2-18 b doesn't even boast Earth-like conditions, Tsiaras said. (The red-dwarf host star bathes K2-18 b in much higher levels of ultraviolet radiation than Earth receives from its sun, for example.)

"It is definitely not a second Earth," he said.

But that shouldn't turn astrobiologists, or anyone else interested in the prospect of life beyond Earth, off to K2-18 b. After all, it's entirely possible — perhaps even likely, given the incredible diversity of alien worlds — that life has taken root on many different types of planets (and, perhaps, moons) throughout the galaxy.

"The only question that we're trying to ask here, and we're pushing forward, is the question of habitability," Tsiaras said. "This is the planet that satisfies more [habitability] requirements than any other that we know right now."

- 5 Bold Claims of Alien Life

- Biodiversity on Some Alien Planets May Dwarf That of Earth

- 9 Strange, Scientific Excuses for Why Humans Haven't Found Aliens Yet

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.