Exoplanet Sees Extreme Heat Waves

Oneextrasolar planet takes heat waves to the extreme: Within six hours,temperatures on the gas giant can soar by more than 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit(555 degrees C).

The intensebaking triggers shock-wave storms that whip around the planet quicker than thespeed of sound, carrying with them skyrocketingheat and high-speed winds.

Known as HD80606b, the gaseous planet was discovered in 2001 by a Swiss planet-huntingteam led by Dominique Naef of the Geneva Observatory. It is about four timesthe mass of Jupiter and is located 200 light-years from Earth.

Wildorbit

HD 80606b'sorbit around its host star ? it's year ? is 111.4 Earth-days long. Its day? one rotation about its axis ? is thought to last about 34 hours (though the scientists don't measure this value directly). The interesting thing isthat its orbit is very elongated, the most eccentric of any known planet.

The giantplanet spends most of its year at relatively comfortable distances that wouldplace it between Venus and Earth in our own solar system. But for just afraction of one day each year, the planet swings to within 0.03 astronomicalunits (AU) of its star. (One AU is the average distance between the Earth and sun.)

"Ifyou could float above the clouds of this planet, you'd see its sun growinglarger and larger at faster and faster rates, increasing in brightness byalmost a factor of 1,000," said Gregory Laughlin, an astrophysicist at theUniversity of California, Santa Cruz. Laughlin is lead author of a new reporton the findings published in the Jan. 29 issue of the journal Nature.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Hyperheat wave

Laughlin andhis colleagues used NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope to measure heat emanatingfrom the planet before, during and after its closest approach to its host star.

The teamfound that in just six hours, the planet's temperature rose from 980 to 2,240degrees Fahrenheit (527 to 1,227 degrees C). At its closest approach, theplanet receives 825 times more irradiation than it does at its farthest pointfrom the star.

While otherhot exoplanets close to their stars, called hotJupiters, are known to have temperatures that reach up to 3,000 degrees F(1,600 degrees C), none has shown such a temperature swing in such a brief period of time.

That kindof temperature change suggests the intense irradiation from the star is absorbedin a layer of the planet's upper atmosphere that absorbs and loses heatrapidly, Laughlin said, adding that if the sun suddenly became 1,000 timesbrighter, it would take much longer before the Earth would double itstemperature.

Somethingstrange must be going on.

Shock-wavestorms

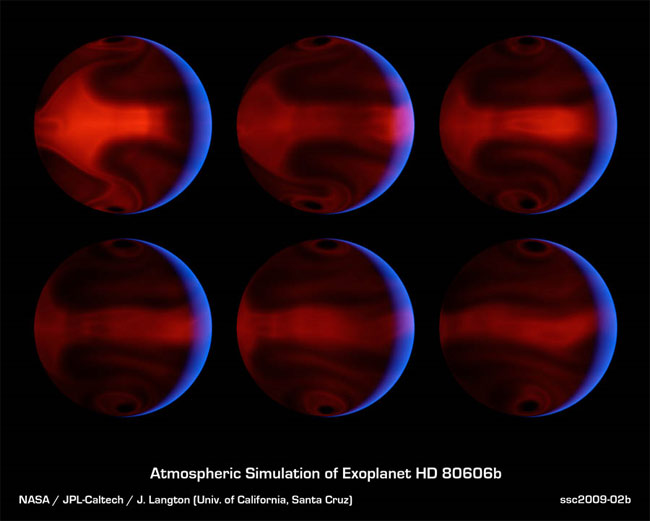

To figureout how the heat affected the planet'satmosphere, study researcher and UCSC colleague, Jonathan Langton, fed theSpitzer data into a computer model. The simulation revealed global storms and shockwaves unleashed in the planet's atmosphere every 111 days as it swings close toits star.

"Asthe atmosphere heats up and expands, it produces very high winds, on the orderof 5 kilometers per second (3 miles per second, or more than 11,000 mph),flowing away from the day side toward the night side," Langton said."The rotation of the planet causes these winds to curl up into large-scalestorm systems that gradually die down as the planet cools over the course ofits orbit."

So even onthe side of the planet facing away from the star, "you'd feel the effectof these shock-wave storms as they pass over you. It's not a place you wouldwant to visit," Laughlin said.

"Thatheating is so intense it's basically like an explosion on the side of theplanet that's getting baked by the star," Laughlin told SPACE.com."That generates these extraordinary storms that begin to echo around theplanet."

If the planet's orbit is aligned just right, it will pass infront of the star, an event known as a transit, on Feb. 14. The transit wouldallow astronomers to refine their calculations of the planet's radius and makeother measurements.

- Video:Planet Hunter

- Images:Spitzer Photo Album

- Top 10Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets