Solar Systems Like Ours May Be Rare

As humans look farther into the universe and discover moreand more planets beyond the sun, many wonder how typical our own solar systemis. Often astronomers in the planet-hunting business say discoveries ofEarth-like worlds are just around the corner.

But a new study indicates our setup may be rare indeed.

A group of astronomers surveyed sun-like stars in the Orionnebula open cluster and found that fewer than 10 percent have enoughsurrounding dust to make Jupiter-sizedplanets.

"We think that most stars in the galaxy are formed indense, Orion-like regions, so this implies that systems like ours may be theexception rather than the rule," said researcher Joshua Eisner, anastrophysicist at the University of California, Berkeley.

That's important because giant planets like Jupiter may beinstrumental in fostering life on rocky worlds like Earth.

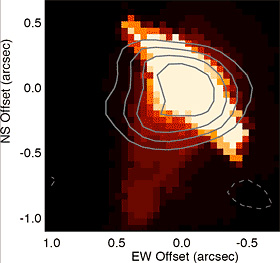

Eisner and his team observed about 250 stars in themillion-year-old Orion Nebula, looking for dense disks of dust surrounding thestars that could be forming planets. They found that only about 10 percent ofthe stars emitted radiation in the frequency that would indicate they havethese proto-planetary disks of warm dust. And only 8 percent of the starssurveyed had dust disks with masses greater than one-hundredth the mass of thesun, a mass thought to be the lower limit for formation of Jupiter-sizedplanets.

These findings seem to agree with what planet hunters arefinding so far when they use radial velocity studies to detect extrasolarplanets around other stars. (The radial velocity approach involves looking fora wobble in a star's motion caused by the slight gravitational pull of anorbiting planet.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The current numbers are suggesting 6 to 10 percent ofstars have Jupiter-sized planets, which is exactly consistent with ourfindings," Eisner told SPACE.com.

The researchers will detail their findings in the Aug. 10issue of the Astrophysical Journal.

Snapshot in time

Still, it's too soon to completely despair of finding theuniverse filled with Jupiters around other suns.

Since the survey only looked at dust around the stars, andwould not have detected any already-formed planets, it could be that some ofthose sun-like stars already had planets.

"Perhaps we?re only detecting the stars that have notformed planets yet," said John M. Carpenter, an astronomer at Caltech whoworked with Eisner on the Orion research. "Perhaps some other starsalready formed planets. It's only a snapshot in time and as you look at otherclusters at different ages you can build up a better picture."

Other scientists agree there are many unanswered questionsabout solarsystems beyond our own.

"As the precision with which we can measure improves,we find more planets," said Harvard planet hunter David Charbonneau, whowas not involved in the Orion study. "The rate of occurrence has gone upsince we started looking."

He said it's too soon to tell for sure whether Earth'ssystem is atypical, but studies that look at whether other stars have the rawmaterials necessary to form solar systems like our own can help.

"Certainly knowing that there is enough stuff aroundstars to make planets is a crucial step," he said.

Rare life?

If it turns out to be true that sun-like stars withJupiter-sized planets are rare, it may mean that extraterrestriallife is rare as well.

Some scientists have suggested that having our own Jupiterhas been instrumental in forming life on Earth. For one thing, large planetscan protect smaller inner planets from being bombarded too heavily by spacerocks, which could crush any budding bits of life.

Plus, large planets could kick comets and asteroids out oftheir orbits and onto paths toward the smaller terrestrial planets. These spacerocks could be delivery systems for organic materials and water.

"If you don?t have a Jupiter it's kind of hard to builda wet planet," Eisner said.

- Video: Planet Hunter

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- Greatest Mysteries: Does Alien Life Exist?

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.