Ultima Thule Looks Like a Bowling Pin in Space in New Horizons Flyby Photo

The most distant object ever visited by a spacecraft looks a lot like a bowling pin, or perhaps a chicken drumstick.

Early this morning (Jan. 1), NASA's New Horizons probe cruised past Ultima Thule, a small body that lies about 4 billion miles (6.4 billion kilometers) from Earth. At 12:33 a.m. EST (0533 GMT), the spacecraft zoomed within a mere 2,200 miles (3,500 km) of Ultima — more than three times closer than New Horizons got to Pluto during its epic flyby of the dwarf planet in July 2015.

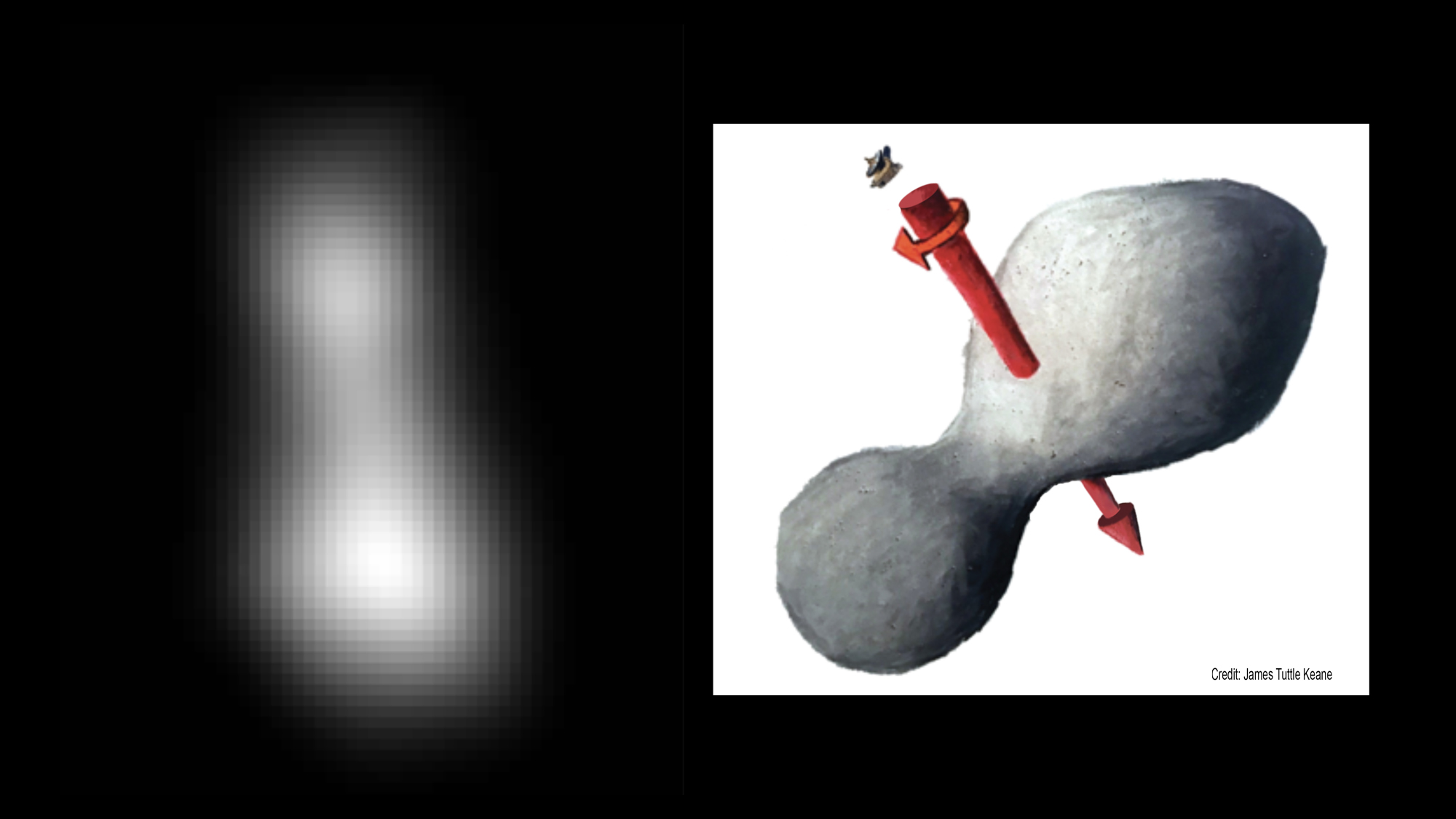

The best images from the flyby won't start coming down to Earth until tomorrow (Jan. 2), but the mission team already has a pretty good idea of Ultima's shape. Photos taken by the probe yesterday (Dec. 31) during its approach reveal that the object is highly elongated, with two distinct lobes — or that it's a system of two close-orbiting bodies. [New Horizons at Ultima Thule: Full Coverage]

"If it's two separate objects, this would be an unprecedented situation in terms of how closely they're orbiting to one another," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said during a news conference today.

So, he added, "my bet would be that it's probably a single object — it's bilobate. And if I'm wrong, I'll tell you tomorrow."

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver, of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, is also putting his money on the single-body option. Small, bilobate objects are common throughout the solar system, Weaver noted during today's news conference. He pointed to Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, which was explored by Europe's Rosetta mission, as an example.

The mission team already had inklings of Ultima's shape. "Occultation" observations made from the ground, when mission scientists watched Ultima pass in front of background stars, had suggested the object is elongated, as had photos taken by New Horizons over the past week or so.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The mission team also now has a better idea of Ultima's size — about 21.7 miles long by 9.3 miles wide (35 by 15 kilometers), Stern said. And the newly released imagery has helped scientists solve a mystery — why New Horizons hasn't seen any substantial brightness variation from Ultima over time, as would be expected with an elongated body. From New Horizons' perspective, Ultima is spinning like a propeller, with its axis of rotation pointed at the probe, mission team members said.

New Horizons will continue beaming Ultima Thule flyby imagery and measurements for a long time to come; all the data won't be in hand until about 20 months from now, Stern said.

And it's possible there could be another deep-space encounter in New Horizons' future. The probe has enough fuel to potentially pull off another flyby, if NASA grants an additional mission extension, Stern has said.

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate) is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom or Facebook. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.