NASA's InSight Lander on Mars Just Set a Solar Power Record!

NASA's InSight lander, which touched down on Mars Nov. 26 and successfully extended its large solar arrays hours later, is already setting records.

During its full first day on the Red Planet, the solar-powered lander generated more electrical power in one day than any previous Mars vehicle has, mission team members said.

"It is great to get our first 'off-world record' on our very first full day on Mars," Tom Hoffman, InSight project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California, said in a statement. [NASA's InSight Mars Lander: Amazing Landing Day Photos!]

"But even better than the achievement of generating more electricity than any mission before us is what it represents for performing our upcoming engineering tasks," Hoffman added. "The 4,588 watt-hours we produced during sol 1 means we currently have more than enough juice to perform these tasks and move forward with our science mission."

The 4,588 watt-hours InSight generated on its first sol, or Martian day, from solar power is well over the 2,806 watt-hours generated in a day by NASA's Curiosity rover, which runs on a nuclear system called a radioisotope thermoelectric generator. Coming in third was the solar-powered Phoenix lander, which generated around 1,800 watt-hours in a day, according to NASA officials.

After sending back its first photo of the landing site and extending its two solar arrays, each of which is about 7 feet in diameter (2.2 meters), InSight got to work photographing its environment and unlatching its robotic arm, which it will eventually use to deploy seismometers and a heat probe to learn about Mars' interior.

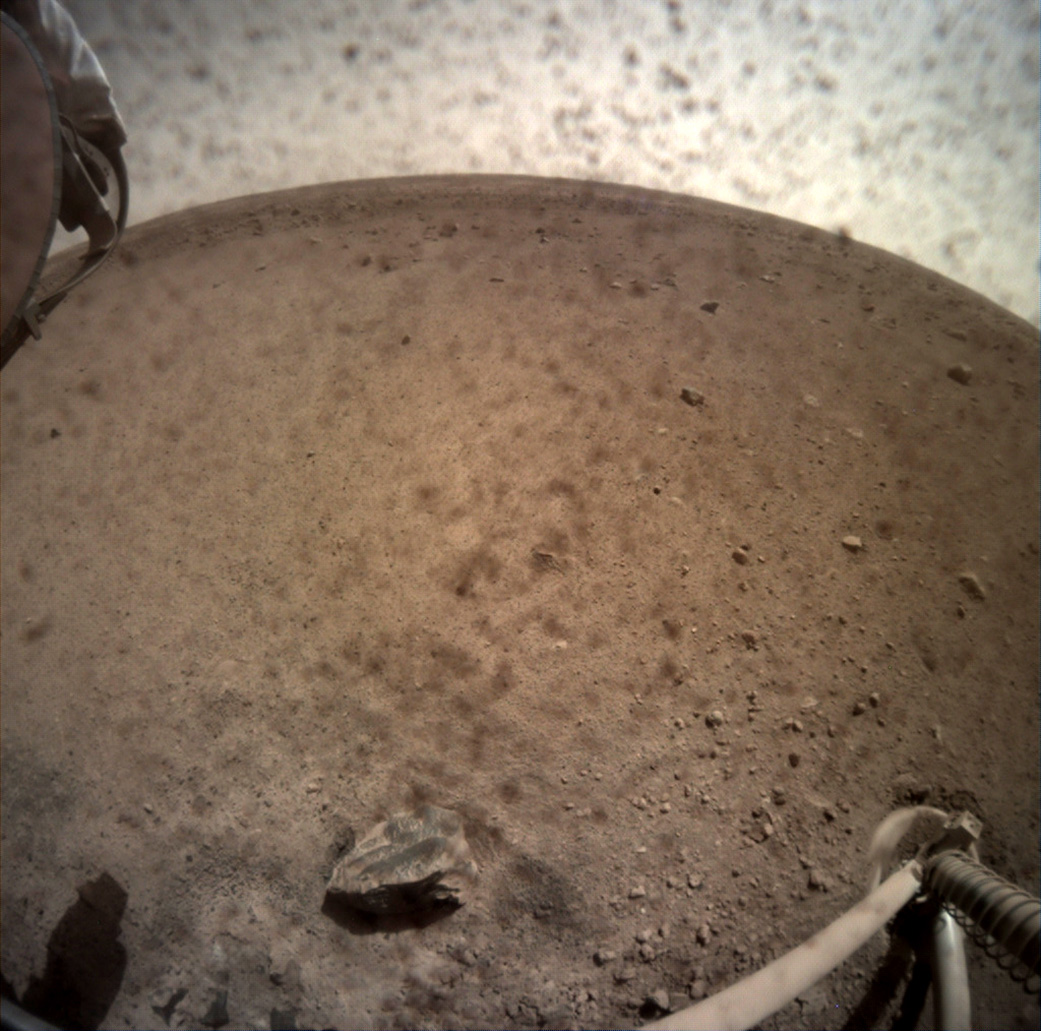

And mission team members are busy inspecting the images they've received so far to learn more about InSight's landing site, a lava plain called Elysium Planitia. They've found that the spacecraft is tilted by about 4 degrees, according to the statement, in a shallow impact crater filled with dust and sand. (This is no big deal; the lander can operate at up to a 15-degree tilt.) A steep slope could have hurt the spacecraft's ability to get enough power from its solar arrays, and landing near rocks could have kept the spacecraft from easily opening both arrays, the researchers said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The science team had been hoping to land in a sandy area with few rocks since we chose the landing site, so we couldn't be happier," Hoffman said in the statement. "There are no landing pads or runways on Mars, so coming down in an area that is basically a large sandbox without any large rocks should make instrument deployment easier and provide a great place for our mole to start burrowing."

So far, the team thinks the immediate area has few rocks, but higher-resolution images coming later on will give a more conclusive view of the surroundings. The team will use those views to plan out exactly how the spacecraft will place its instruments with its mechanical arm.

"We are looking forward to higher-definition pictures to confirm this preliminary assessment," InSight principal investigator Bruce Banerdt, also at JPL, said in the statement. "If these few images — with resolution-reducing dust covers on — are accurate, it bodes well for both instrument deployment and the mole penetration of our subsurface heat-flow experiment." (According to NASA, the spacecraft got its first view of Mars with a lens cover off Nov. 30.)

The $850 million InSight mission is scheduled to run for one Mars year, or nearly two Earth years. The data gathered by the lander will help mission team members map out the Red Planet's interior structure in unprecedented detail, NASA officials have said. This information should, in turn, reveal key insights about the formation of rocky planets in general.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Originally published on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.