Touchdown on Mars! NASA's InSight Lands to Peer Inside the Red Planet

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

PASADENA, Calif. — Mars just welcomed a new robotic resident.

NASA's InSight lander touched down safely on the Martian surface today (Nov. 26), pulling off the first successful Red Planet landing since the Curiosity rover's arrival in August 2012 — on the seventh anniversary of Curiosity's launch, no less.

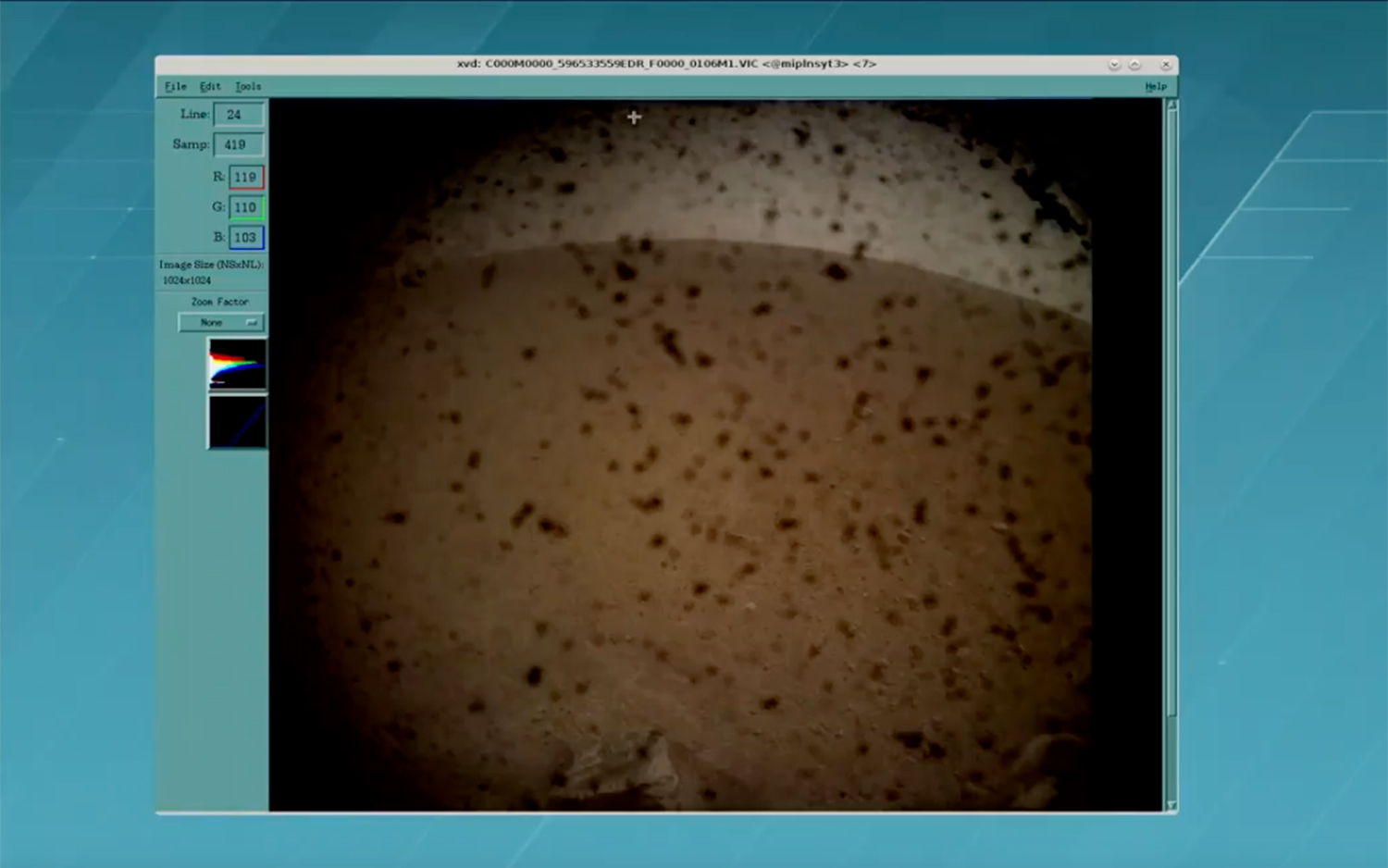

Signals confirming InSight's touchdown came down to Earth at 2:53 p.m. EST (1953 GMT), eliciting whoops of joy and relief from mission team members and NASA officials here at the agency's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), which manages the InSight mission. A few minutes later, the team received confirmation from the lander that it's functioning after the landing. [NASA's InSight Mars Lander: Full Coverage]

"It was intense, and you could feel the emotion," said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine, who was in the control room here at JPL during the landing. "It was very, very quiet when it was time to be quiet and of course very celebratory with every little new piece of information that was received. It's very different being here than watching it on TV, by far, I can tell you that for sure now that I've experienced both."

But the tension didn't completely dissipate until 8:30 p.m. EST (0130 GMT on Nov. 27), when mission team members learned that InSight successfully deployed its solar panels. Without those arrays extended, the lander could not survive, let alone probe the Red Planet's interior like never before — the main goal of the $850 million InSight mission.

The agonizing delay was unavoidable; NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter wasn't in position to relay the deployment confirmation to mission control until about 5.5 hours after touchdown, agency officials said.

If the arrays do unfurl as planned, InSight will join a relatively select club. Less than 40 percent of all Mars missions over the decades have successfully arrived at their destination, be that an orbital path around the planet or its dusty red surface.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A long road to Mars

InSight launched on May 5 from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, in the first-ever liftoff of an interplanetary mission from the U.S. West Coast. (Florida's Space Coast is the traditional jumping-off point for such far-flung voyagers.)

InSight shared its Atlas V rocket ride with two briefcase-size cubesats called MarCO-A and MarCO-B, which have been making their own way to Mars over the past 6.5 months. The MarCO duo (whose name is short for "Mars Cube One") have been embarked on an $18 million demonstration mission, which seeks to show that tiny spacecraft can explore deep space.

MarCO-A and MarCO-B also played a key role in today's excitement, relaying data from InSight to mission control here at JPL during the lander's harrowing entry, descent and landing (EDL) sequence.

And harrowing it was. InSight hit the thin Martian atmosphere at about 12,300 mph (19,800 km/h), nailing its entry angle of exactly 12 degrees. If the lander had come in any steeper than that, it would have burned up; any shallower, and it would have skipped off the atmosphere like a flat stone across a pond.

As the lander streaked through the Martian skies, its heat shield endured temperatures around 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit (1,500 degrees Celsius) — hot enough to melt steel. Atmospheric drag slowed InSight down tremendously, to about 1.7 times the speed of sound, at which point the lander deployed its supersonic parachute.

InSight soon fired up its small onboard thrusters to decelerate further, finally touching down on a flat equatorial plain called Elysium Planitia at around 5 mph (8 km/h). (These numbers are based on pre-landing modeling work by the InSight EDL team; the actual figures may end up being slightly different.)

All of this happened in just 6.5 minutes — InSight's total travel time in the Martian air, from atmospheric entry to touchdown. The lander's EDL sequence was a bit shorter than Curiosity's famous "7 minutes of terror" experience, which featured a rocket-powered sky crane that lowered the heavy, car-size rover onto the Martian surface on cables. (InSight's EDL mirrors that of NASA's Phoenix lander, which touched down near the Red Planet's north pole in May 2008. InSight's body is also based heavily on that of Phoenix; both landers were built for NASA by aerospace company Lockheed Martin.)

MarCO-A and MarCO-B didn't follow InSight onto the surface. The bantam probes flew right on by Mars, their work done and their place in history as the first interplanetary cubesats cemented. [NASA's Mars InSight Lander: 10 Surprising Facts]

"We believe that this is a really interesting technology overall, and we've really shown something unique in deep space that will allow us to further future missions in a compact and efficient way," MarCo-A mission manager Cody Colley of JPL said here yesterday (Nov. 25) during a pre-landing news conference.

Their work is probably done, I should say: It's possible that MarCO-A and MarCO-B could observe an asteroid or other celestial body if their paths bring them close enough, and if funding for an extended mission is granted, John Baker, NASA's program office manager for the MarCO mission, told Space.com.

Probing the Martian interior

As exciting as the landing was, it was just the prelude to the main event — InSight's science work on the Red Planet.

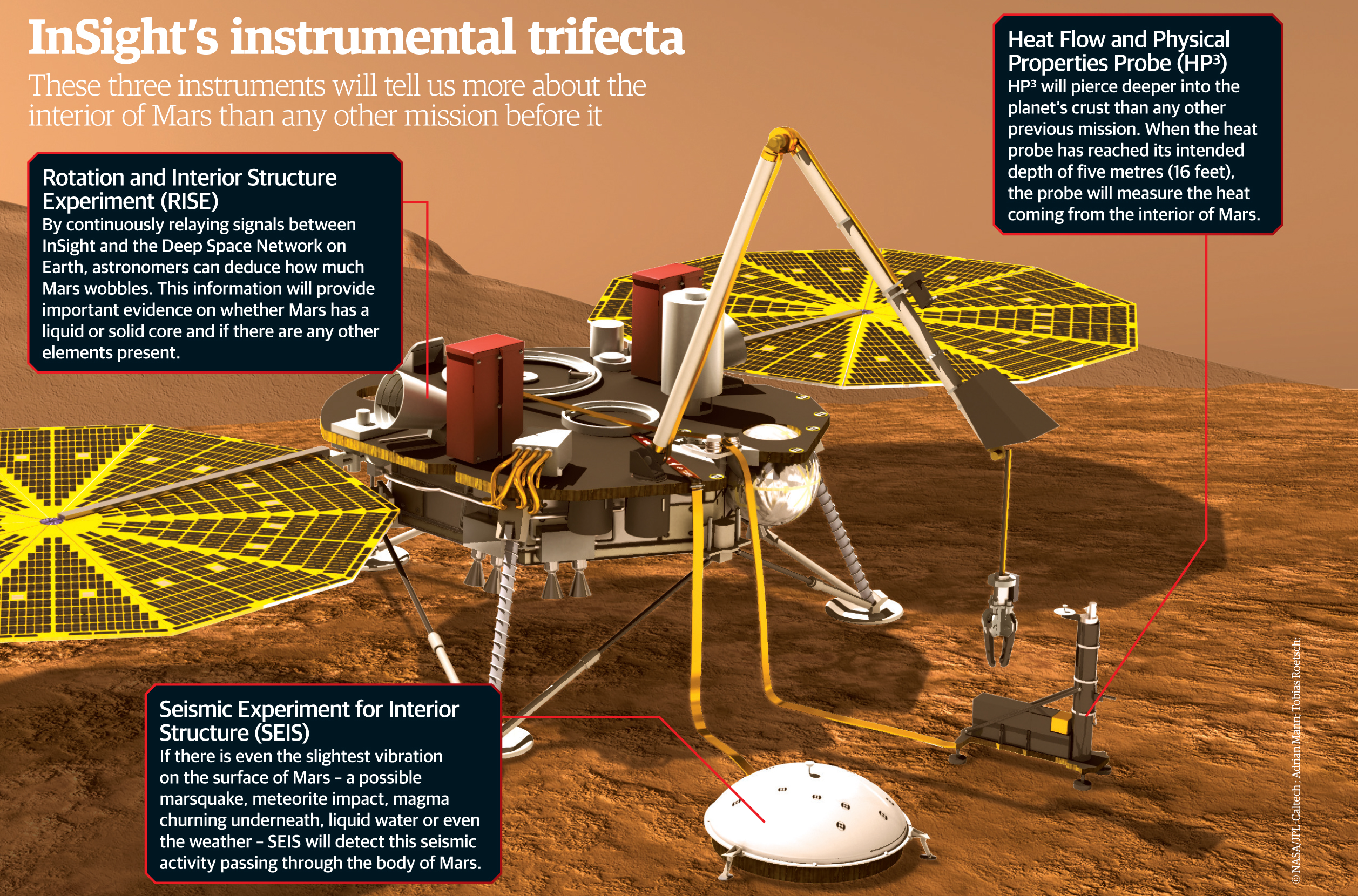

Over the next two Earth years, the lander will probe Mars' interior structure and composition in unprecedented detail. InSight will use two main science instruments to do this: a heat probe that will hammer itself up to 16 feet (5 meters) beneath the Martian surface, and a suite of three incredibly precise seismometers, which will be on the lookout for "marsquakes," meteorite strikes and other jolts.

"Incredibly precise" doesn't do these seismometers justice, actually.

"They can see vibrations with an amplitude of about the size of an atom — maybe a fraction of an atom," InSight principal investigator Bruce Banerdt, also of JPL, said during yesterday's news conference.

The seismometer suite is therefore encased in a vacuum chamber, to minimize disturbances that could muck up the data. In late 2015, the mission team detected a leak in this chamber. The leak was fixed, but not in time for InSight to launch in March 2016, as originally planned. Launch windows for Mars missions roll around just once every 26 months, so the lander had to wait until this past May to get off the ground.

The science team will also track InSight's position in space using the 789-lb. (358 kilograms) lander's communications gear. This information will allow scientists to measure the slight wobble of Mars' axis of rotation, which in turn will help them better understand the planet's core, NASA officials have said.

Together, all of this data will give scientists an unprecedented look at the Red Planet's interior.

"That is the goal of the InSight mission — to actually map out the inside of Mars in three dimensions, so that we understand the inside of Mars as well as we have come to understand the surface of Mars," Banerdt said.

And scientists can use Mars as a sort of laboratory to understand how rocky planets in general form, he added. That's because the Red Planet's insides have been more or less frozen in place since shortly after Mars formed about 4.5 billion years ago. We can't look to Earth as a time capsule in this way because our planet's insides have been roiled continuously over the eons by plate tectonics, mantle convection and other processes.

InSight (whose name is short for "Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport") features an unusual degree of international cooperation. The burrowing heat probe was provided by the German Aerospace Center, and France's national space agency CNES led the consortium that developed the seismometer suite. [Mars InSight: NASA's Mission to Probe Red Planet's Core (Gallery)]

"A slow-motion mission"

Don't expect InSight to dazzle you with pretty pictures. The mission isn't interested in cool surface features, which explains why it landed on Elysium Planitia; the plain is smooth and flat with a paucity of boulders, boosting the odds of a safe landing (and of the burrowing heat probe being able to get deep down into the Martian dirt). And InSight is a lander, not a rover, so any photos that it takes over the course of its mission will depict the same terrain.

It'll also take a while for the spacecraft to get up and running on Mars. InSight will use its robotic arm to place the heat probe, the seismometer suite and a weather shield (which will surround the seismometers) on the ground.

No other Mars mission has done such an instrument deployment — science gear tends to be fixed to the bodies or arms of Red Planet spacecraft — and the InSight team wants to make sure they get it right. So, once they get a look at InSight's Martian surroundings, they'll practice the deployment over and over using a testbed lander here at JPL.

Actual deployment probably won't happen until two or three months from now, Banerdt said. And it'll take another month or so to calibrate the instruments for use on the Red Planet.

So, it'll be at least six months before the InSight team even "gets a glimmer of what we're looking for," Banerdt said. And it'll likely take the full two-year mission lifetime, or close to it, to get a really detailed look at the Martian interior.

"Once we get to the surface, InSight is a slow-motion mission," Banerdt said.

This story was updated at 10:20 p.m. EST to state that NASA has received confirmation that InSight's solar arrays have deployed.

Space.com managing editor Tariq Malik contributed to this story from Pasadena. Senior writer Meghan Bartels contributed from New York City. Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate) is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom or Facebook. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.