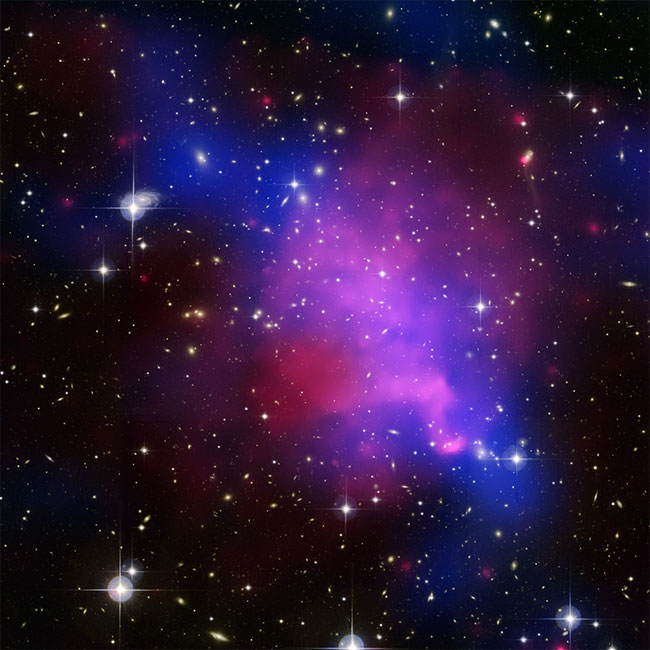

Observations of a distant galaxy cluster collision reveal a core of invisible matter devoid of glittering galaxies—something that is hard to explain by current theories.

The invisible stuff is what astronomers call dark matter. They don't know what it is, but they know it exists because of its gravitational effects on normal matter and light.

If confirmed, the new results could force scientists to rethink their ideas about how dark matter behaves, or even conjure up a whole new class of dark matter. But scientists say they will await further confirmation before taking such radical steps.

The findings, to be detailed in an upcoming issue of Astrophysical Journal, are in complete contrast to observations of the Bullet Cluster, another well-studied galaxy cluster collision.

"These results challenge our understanding of the way clusters merge," said study team member Andisheh Mahdavi of the University of Victoria, British Columbia. "Or, they possibly make us even re-examine the nature of dark matter itself."

When clusters collide

Galaxy clusters are made up of several hundred galaxies bound together by gravity. They are the largest structures in the universe; when they collide, they generate an enormous amount of energy, second only to the Big Bang event that scientists think gave birth to the universe.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Galaxy clusters contain three main components: individual galaxies with stars made up of "normal" matter, hot gas, and a mysterious substance called dark matter. Scientists have so far been unable to directly observe dark matter, and have only been able to detect it by measuring its gravitational effect on light.

Large clumps of dark matter, called halos, contain so much mass that they warp passing starlight, an effect scientists call gravitational lensing. This was how scientists spotted the core of the colliding galaxy cluster system known as Abell 520. Surprisingly, the core was rich in dark matter and hot gas but contained no visible galaxies.

Current theories predict that dark matter and galaxies should stay together even during violent mash ups because they are drawn to each other's gravity but that hot gas will drag behind because it feels the effects of a cosmic drag that is similar to air resistance. This was what scientists saw happening in the Bullet Cluster.

Abell 520's missing galaxies were found in a separate part of the sky with little or no dark matter associated with them. How or why the dark and normal matter separated is unknown and flies in the face of scientists' current understanding of the cosmos.

"It blew us away that it looks like the galaxies are removed from the dark matter core," said study team member Hendrik Hoekstra, also of the University of Victoria. "This would be the first time we've seen such a thing and could be a huge test of our knowledge of how dark matter behaves."

Troubling explanations

The researchers propose two possible explanations for their findings, but both are equally unsettling for scientists.

The first option is that the galaxies were catapulted out of the dark matter halo by some kind of gravitational "slingshot" effect. The problem, however, is that computer simulations have failed to produce slingshots powerful enough to cause such a separation.

An alternative idea is that there is more than one form of dark matter and that the different types interact with each other. But conceding such a possibility would mean conjuring up yet another unknown substance that is as mysterious as dark matter itself.

Cautious for now

Avi Loeb, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who was not involved in the study, called the new results "very interesting" but said he will take a wait-and-see approach for now.

"If it is confirmed, it may mean that dark matter is not really collisionless … and can interact with itself," Loeb said, but "I think most people that work in this area would be cautious."

Mahdavi and his team have secured more time with Chandra and the Hubble Space Telescope to confirm the dark matter findings.

"I think it would be prudent to wait until this data is collected … before we make far-reaching conclusions about the nature of dark matter," Loeb told SPACE.com.

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- Top 10 Strangest Things in Space

- VIDEO: The Biggest Cosmic Collisions

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.