'Star Trek Adventures' Is the Franchise's Best RPG Yet

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

On Feb.11, 2018, the last episode of the excellent "Star Trek: Discovery" first season aired on CBS All Access. For 45 glorious minutes, I could enjoy a brand-new "Star Trek" adventure, full of action, drama, intrigue and classic, big-idea sci-fi. And then, just like that, it was all over. After 15 episodes, CBS wouldn't be providing any more "Star Trek" until 2019.

And if CBS wouldn't make a "Star Trek" series for me, I had no choice but to make my own.

Last June, British publisher Modiphius released "Star Trek Adventures:" a tabletop pencil-and-paper role-playing game that lets enterprising players bring their own futuristic voyages to life. I hadn't played a tabletop RPG since 2012, and I hadn't played a "Star Trek" tabletop RPG since 2005. But in the past few years, I've fallen in love with the franchise all over again. After 741 episodes and 13 movies, wasn't it time to try making one of my own? [6 'Star Trek' Captains, Ranked from Worst to Best]

The developers at Modiphius were generous enough to send Space.com a PDF copy of the rules. I realized quickly that I had a lot of work ahead of me if I wanted to make an adventure worthy of Gene Roddenberry's world — just working through the rule book and organizing my first session took about three months. But if you're patient, imaginative and have a fair amount of disposable income on your hands, you may find that the most memorable "Star Trek" adventure is the one you create with your friends.

What is "Star Trek Adventures"?

The Venn diagram of "people who like 'Star Trek'" and "people who play tabletop RPGs" probably has a pretty large intersection, but big, licensed games almost always draw in a new crowd. As such, it's possible that some Trekkies reading this piece have never played a tabletop RPG before. Here's how it works:

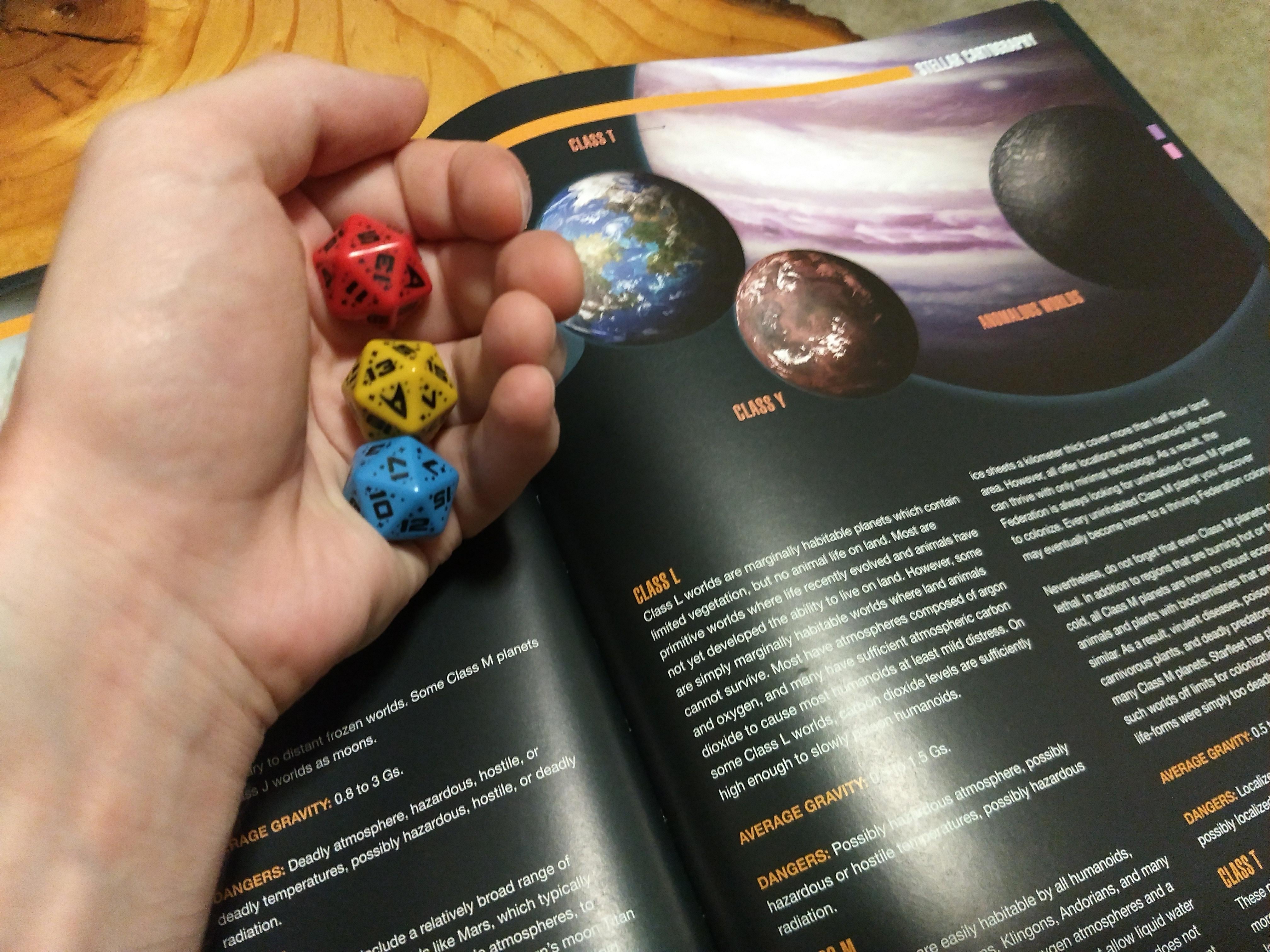

You and your friends gather together around a table, armed with some paper, pencils and dice. (Pizza and beer are optional, but highly recommended.) Three to five players take the roles of characters on a Federation starship. Perhaps one of them is an inquisitive Vulcan science officer, or a hardened Bajoran freedom fighter, or an even-tempered human captain; the rules allow for almost any kind of character you've seen on the shows, and then some.

The final player is called the Game Master. It's his or her responsibility to narrate the story, adjudicate actions, act out nonplayer characters and structure the overall adventure. In other words, the players are like the star actors, while the GM is like the writer, producer, director and supporting cast, all in one.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In short, tabletop RPGs are half board game, half improvisational theater. The rules dictate the general actions you can take, like firing a phaser or piloting a starship, but how you tackle challenges and interact with your fellow crewmembers is up to you. RPGs are a form of collaborative storytelling, with game systems in place to keep things fun, unpredictable and fair.

The basics

While "Star Trek Adventures" is the newest "Star Trek" RPG, it's not the first by any means. Companies have been giving players the opportunity to sit in the captain's chair ever since 1978, with everyone from Heritage Models to the RPG publisher FASA trying their hand at game design.

I can't speak to the entire history of "Star Trek" RPGs, but I did play two of them back in high school: the 1998 Next Generation ruleset from Last Unicorn Games, and the 2002 "Star Trek" Roleplaying Game from Decipher. Without going into exhaustive detail about either one, I can say that "Star Trek Adventures" is — for the most part — a cleaner, simpler and more balanced experience than the games that preceded it.

"Star Trek Adventures" runs on Modiphius' signature 2d20 system. All you need to play, as either a player or a GM, is the core rule book ($59). As in most RPGs, any time you take an action whose outcome is uncertain (whacking a Gorn warrior over the head, flying a shuttlecraft through a stellar flare, persuading a hostile Romulan ship to stand down — standard Starfleet stuff), you'll roll dice to determine whether you succeed or fail.

To help determine success or failure, each character has six attributes: Control, Fitness, Presence, Daring, Insight and Reason. These represent a character's physical and mental traits. In addition, each character has six disciplines: Command, Security, Science, Conn (computers and piloting), Engineering and Medicine. These represent a character's Starfleet training. These stats, combined with rolling two twenty-sided dice, determine whether an action succeeds or fails. Characters can also "purchase" extra dice to improve their odds with a resource called "momentum," which they’ll gain and spend constantly throughout an adventure.

Now, here's the fascinating thing about "Star Trek Adventures" as opposed to, say, "Dungeons & Dragons": your Disciplines are not inherently linked to any Attribute. You can't "min-max" your stats, assuming that your tactical officer will need high Daring, high Security, and nothing else.

Instead, Attributes and Disciplines are both situational. For example, let's return to our hypothetical security officer. Daring + Security is indeed very useful for grappling with enemies in close combat. But to fire a phaser requires Control + Security instead. Interrogating a prisoner might require Presence + Security; investigating a crime scene could be Reason + Security; chasing down a fleeing Cardassian could be Fitness + Security. Both specialized and generalized characters are viable in "Star Trek Adventures," and that's a refreshing change of pace.

Between its approachability and its versatility, "Star Trek Adventures" won me over in a big way. Adjudicating actions is simple and clear, while just about every character will have a time to shine. Whether it's a doctor making a breakthrough cure for an alien plague or an engineer patching up a shuttlecraft just in time to outrun the deadly ion storm (both of these things actually happened in my game — in the very first session!), players will be able to do the same incredible things that their favorite characters do on-screen, right out of the gate. [The Evolution of 'Star Trek' (Infographic)]

Starfleet's finest

"Star Trek" isn't about making a character who can do exactly one thing impeccably; it's about making a character who's versatile and adaptable, like any good Starfleet officer. It's a good thing, then, that character creation is just as fun and approachable as the core game.

If you've ever made a character in D&D, or "Pathfinder," "Star Wars," or any other mainstream RPG, character creation for "Star Trek" will feel familiar, but with a few smart twists. The default setting for "Star Trek Adventures" is that a group of players act as the senior staff of a starship or starbase, just like one of the TV shows. As such, every character is either a Starfleet officer or a petty officer — anything between a yeoman and a captain.

You have two choices to make a character: Lifepath or creation-in-play. The latter lets you distribute some stats to start, then fill in the blanks as you play, and it's easily the less interesting of the two. Lifepath lets you build a character that's uniquely yours, through either purposeful construction or randomized rolls. While it might be tempting to craft the perfect Starfleet officer, my players and I actually had much more fun randomizing our Lifepaths. There are even period-appropriate randomized tables for choosing a race, since a Voyager-era game will have more playable races than an Enterprise-era one. It's that sort of attention to canonical detail that gives the book — and the game — a lot of its flavor.

From there, you'll choose your race (Andorian, Bajoran, Betazoid, Denobulan, Human, Tellarite, Trill or Vulcan), your upbringing, your Starfleet specialization and even two career-defining events, such as a transporter accident or a first contact procedure. As you go, you'll also develop Focuses, which help you get more successes on good dice rolls, as well as Values, which determine what's most important to your character. A Focus could be something like hand-to-hand combat or astronavigation, while a Value could be "Meticulous Pride in My Work" or "The Price of Peace Is Vigilance." Players are encouraged to make up their own Focuses and Values, which adds to the free-form and personalized nature of the game.

What's fantastic about the character creation system is that it's almost impossible to make a "bad character." Having moderately good attributes and disciplines across the board rather than a handful of specializations can actually be a good thing, since you never know which combinations will be useful in any given situation.

Another thing I absolutely adore about "Star Trek Adventures" is that the characters are balanced. In the "Last Unicorn" and "Decipher" worlds, a team of players representing a bridge crew would have wildly divergent skill sets. A captain would be a much higher level than an ensign and have a whole bevy of high-level skills, whereas an ensign might have only one or two useful abilities. It made it much harder for a GM to balance a game and for each player to take the spotlight.

Instead, "Star Trek Adventures" does away with extensive skill trees and "levels." All Starfleet officers are extremely proficient, and have a chance to shine in their chosen field, regardless of experience level. Young officers get a talent that lets them reroll failed dice; veteran officers get a talent that lets them create advantageous situations more easily.

Granted, this means that there are situations in which an ensign could have nearly the same skill level as a captain, but this didn't cause any issues in my game. After all, all RPGs are an abstraction, and in theory, a player who creates an ensign character didn't do so with the intention of staging an in-game coup.

Fire phasers!

While "Star Trek" as a series is very much about getting along, it's impossible to go more than an episode or so without the characters firing a phaser or throwing a punch. Besides, combat in RPGs is usually one of the most fun parts, where dramatic tension comes to a head and characters get to save the day through tactical thinking and strategic maneuvers.

The first thing to keep in mind about combat in "Star Trek Adventures" is that it isn't "Dungeons & Dragons." Your characters are not fantastical adventurers squaring off against impossible beasts. As such, combat is usually fast and furious. A standard phaser blast can tear away half of your character's hit points in a single shot, and an unlucky stroke of a bat'leth could put him in sick bay (if he's lucky) in even less time.

Still, I much prefer the combat in "Star Trek Adventures" to the "blink and you're dead" approach of Last Unicorn, or the "player characters pretty much can't die" approach of Decipher. Players have a pool of "stress" that represents how much abstract damage they can take in combat. Drain that (or deal a ton of damage in one go), and they sustain injuries. If a character sustains three nonlethal injuries, or two lethal injuries, he or she is dead. One injury will usually knock a character out, but there are ways to mitigate this, too.

In keeping with the free-form nature of the game, you won't have to worry about battle grids and turn orders and minutiae like that. There are rules for ducking behind cover, firing wide-range phaser beams and moving around the battlefield, but they're easy to keep track of with a piece of paper and some glass beads — or even just some colored pencils.

(I tried "theater of the mind"-style combat, without beads or paper, at first, but it's a little too hard to keep track of distances that way. "Star Trek Adventures" is not as demanding as combat-heavy fantasy RPGs, but it's still important to know whether you're in melee range of an enemy, or how far away you stand when you shoot.)

Combat itself is delightfully simple, with a couple clearly defined rolls for different types of attacks. Characters can actually take a whole lot more actions during combat, from aiming their weapons to setting up elaborate traps, but the rules for those additional actions tend to get a little complex and esoteric, particularly for players who may not have a copy of the rule book handy. This is something of a recurring theme with "Star Trek Adventures.” The basics are simple, but the specifics can get complicated — sometimes unnecessarily so.

The final frontier

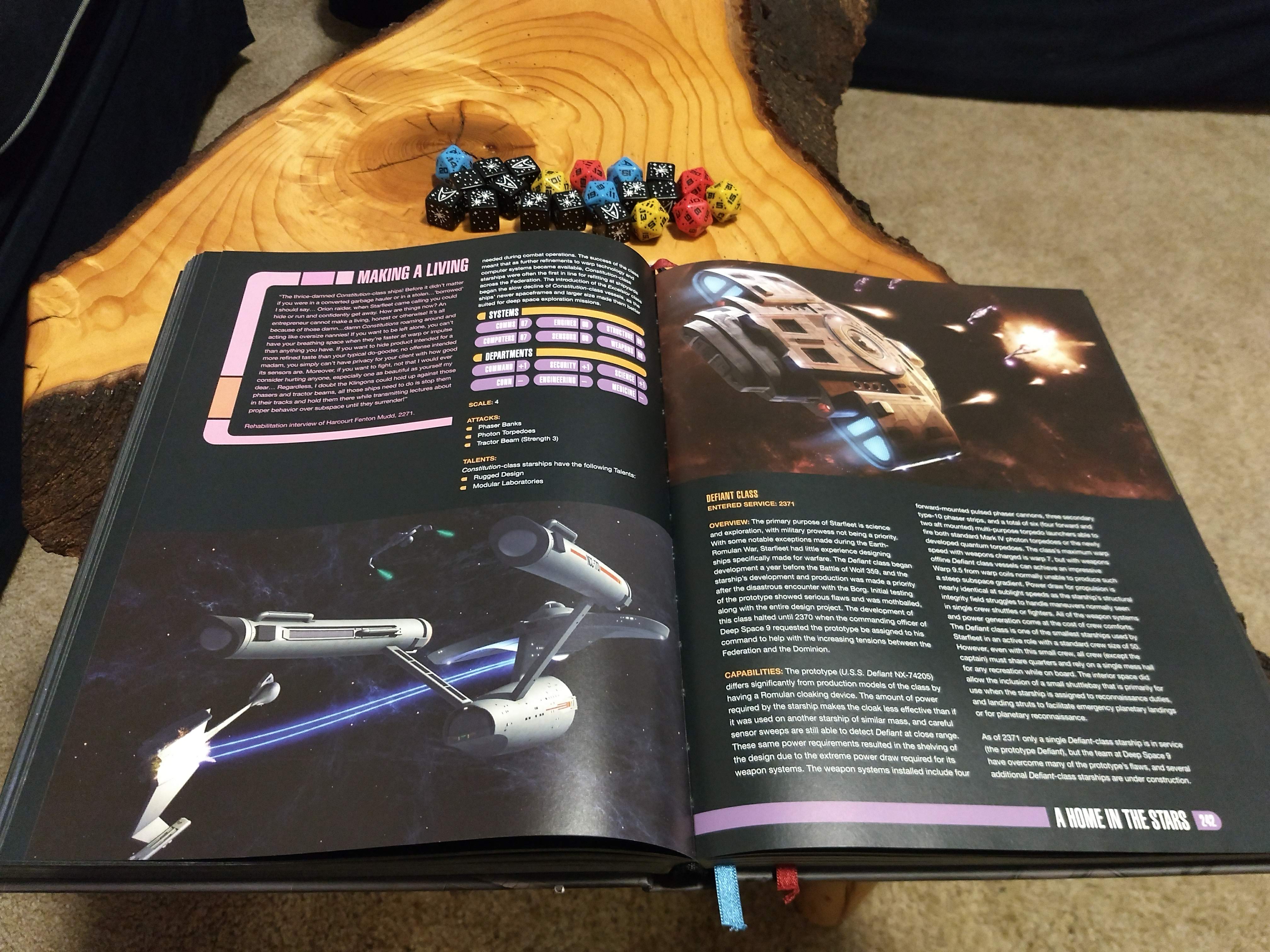

You can't have a "Star Trek" game without starships, and "Star Trek Adventures" provides plenty of these. Just as the players create their own characters, they will also collaborate to create their very own starship, complete with a name and NCC number designation.

Creating a starship is, for the most part, just as smooth and interesting as creating a character. I was worried that my players might each have wildly conflicting ideas about their home in the stars, but within half an hour, they'd ironed out everything from its mission profile (border patrol), to its special abilities (versatile onboard laboratories), to its name and registry number (USS Kumari, NCC-1066.)

Like characters, there are plenty of ways to make your ship unique, from its space frame to its profile. You could have a Galaxy-class vessel like the Enterprise-D on a deep-space exploration mission or a Defiant-class vessel defending the Federation from the Jem'Hadar. When you take an action aboard a starship, the ship itself gets an extra die roll to help players out. Easy enough. [The 15 Best Ships on Star Trek, from V-ger to the USS Vengeance]

But things get complicated in starship combat. Honestly, what the rule book needed was an example of starship combat in play, from the beginning of the encounter to the end. What we got instead is about 20 pages of complicated rules, procedures and strategies. After reading through the whole section about three times, it still took an hour to run our first two rounds of starship combat (the Kumari against a Klingon battlecruiser), and my players weren't at all clear about which actions required them to take a turn (recharging shields), and which were passive (certain sensor sweeps).

In all fairness, after those two clunky rounds, we all had a much better understanding of how things worked. And battles in space feel exciting, dangerous and impactful; two rounds were enough for the players to disable the battlecruiser's engines, and for the Kumari to sustain threatening hull damage. Like ground combat, you can decide epic confrontations in just a few rounds — but space combat rounds take much, much longer.

It's also worth pointing out that while the core rule book has a generous amount of "Star Trek: The Next Generation"-era ships, it has only one original-series-era ship (Constitution class), and absolutely nothing for "Star Trek: Enterprise"-era games. The Command Division sourcebook fills in the gaps, but it's a bit disappointing that the rules claim you can play in any "Trek" time period, then all but require you to buy another book to make the most of some of them.

Structural deficiencies

I'm comfortable saying that "Star Trek Adventures" is the best of the three "Trek" RPGs that I've played. That doesn't mean it's flawless, however. The core rule book has two major flaws: its layout and its overwhelming focus on TNG-era games.

While most RPG core rule books start out with mechanical information and discuss lore later on, the "Star Trek Adventures" core rulebook front-loads background information, even though it's the sort of background information that most people who want to play a "Star Trek" RPG will already know.

After a brief example of play (and, again, more of these would be helpful), the book launches into 70 pages of extensive backstory about the United Federation of Planets and Starfleet. This doesn't really explain how to play, and while I understand that you need to present this information somewhere in a core rule book, front-loading it keeps players from getting to the meaty stuff right away.

Furthermore, the chapter on combat is separated from the chapter on performing basic tasks by character creation and a long, strange digression about exploring alien worlds. The whole book is a little like this; all of the information you need is in there, but facts that need to go together are often dozens of pages apart. At least the index is pretty comprehensive.

As stated above, there's also a ton of focus on the TNG era, without much consideration for what it'd be like to run a game in the time of Archer or Kirk. A few sidebars clarify how to deal with earlier eras, but a full section or chapter dedicated to it might have been helpful. Some of the sourcebooks delve into this information further, but they're expensive (about $40 per book) and prioritize lore information over mechanical additions.

Bottom line

In spite of a confusing layout and some unnecessarily crunchy rules, "Star Trek Adventures" is the most accessible, balanced and imaginative "Star Trek" game to date. Everything from creating characters to buying momentum incorporates a bit of unpredictability, resulting in adventures where the characters can succeed and fail in spectacular ways. Both the players and the GM have to play fair, and it's clear from the book's gorgeous design and informative sidebars how much the developers love the source material.

If you can find a few like-minded galactic explorers, you should at least try the free quick-start rules for "Star Trek Adventures." It'll take about 3 hours to pick up and play, and by the end of it, you'll know for sure whether you want to continue your explorations. My players sure did; we've been going strong since June fighting Romulans, solving murder mysteries, rescuing Federation scientists, rooting out spies, confronting moral dilemmas and more. I even wrote some theme music for the group.

Once you get comfortable with the rules, there are only two directives to follow: engage, and boldly go.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Marshall Honorof is a senior editor for Tom's Guide, overseeing the site's coverage of gaming hardware and software. He comes from a science writing background, having studied paleomammalogy, biological anthropology, and the history of science and technology. After hours, you can find him practicing taekwondo or doing deep dives on classic sci-fi.