Chang'e-4: Visiting the Far Side of the Moon

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

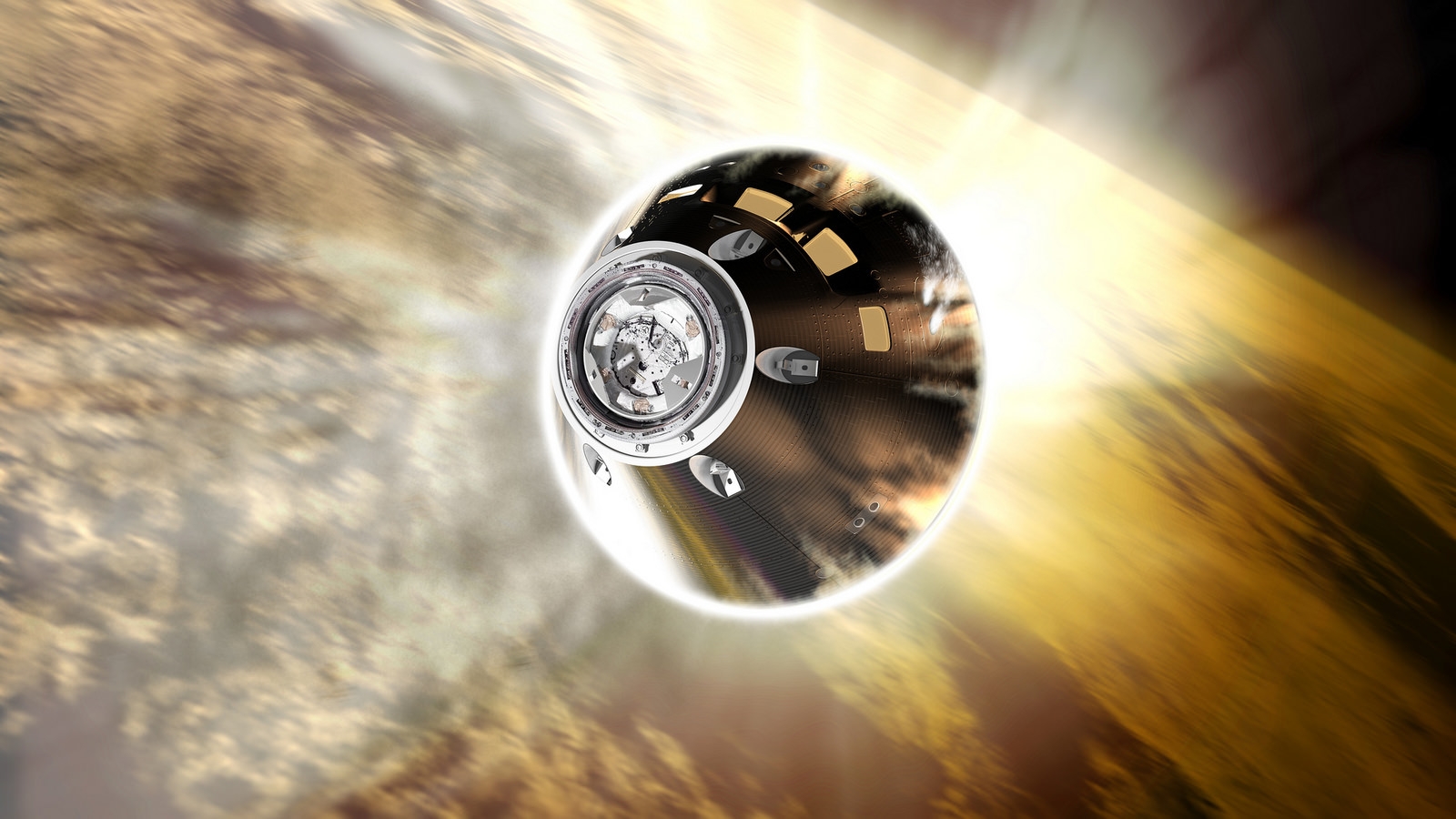

When China's Chang'e-4 mission reaches the lunar surface in December 2018, it will become the first mission to make a soft landing on the far side of the moon. The combination lander-rover will explore the several aspects of the so-called "dark" side, as well as study the universe's radio sky.

A key element of the mission was the May 2018 launch of the Queqiao relay satellite, which will pass information from Chang'e-4 (CE-4) back to Earth. Both missions are led by the China National Space Administration (CNSA).

The Chang'e program was named after the Chinese goddess of the moon, and "Queqio" means "bridge of magpies." According to China's state-run Xinhua news service, Queqio is based on a Chinese folktale, where "magpies form a bridge with their wings on the seventh night of the seventh month of the lunar calendar to enable Zhi Nu, the seventh daughter of the goddess of heaven, to cross and meet her beloved husband, separated from her by the Milky Way."

Previous Chang'e missions set the stage for Chang'e-4:

- In 2007, Chang'e-1 mapped the moon from orbit and then crashed into the lunar surface in 2009 as planned.

- In 2010, Chang'e-2 orbited the moon, and left orbit to swing past an asteroid and then explore deeper into space.

- In 2013, Chang'e-3 with the Yutu rover became the first Chinese spacecraft to land on the moon.

- In 2014, the test capsule Chang'e-5-TI flew past the moon and looped back around to Earth to practice for an eventual lunar sample return mission.

[Inforgraphic: China's Moon Missions Explained]

On the far side

While satellites and astronauts have flown by and observed the far side of the moon, no mission has yet managed to touch down on its surface. But that's not because scientists aren't interested; retrieving a sample from the far side of the moon was an important goal in the 2013-2022 Planetary Science Decadal Survey.

Because the moon is tidally locked to the Earth, those of us bound to the planet can only catch a glimpse through satellite imagery. But, despite pop culture references to the contrary, the far side isn't dark; it receives solar light when the moon sits between Earth and the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The far side contains the South Pole-Aitken basin, an impact site over 1,553 miles (2,500 kilometers) across that exposes the deepest parts of the lunar crust. The enormous basin is the oldest impact feature on the moon, as well as the deepest, with a rim-to-floor distance of almost 8 miles (13 km), more than 6 times as deep as the Grand Canyon.

CE-4's landing site will be the southern floor of the Von Karman crater, a crater 112 miles (180 km) across lying within the South Pole-Aitken impact basin. The crater was named after a Hungarian-American mathematician, aerospace engineer and physicist.

The spacecraft will carry a suite of international payloads from Germany, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, and Sweden. Many of these are similar to the instruments found on Chang'e-3, since CE-4 was originally designed as a backup.

"Chang'e 3 lunar probe used a slow and arc-shaped landing, while as for Chang'e 4 lunar probe, we have to adopt a steep and almost vertical landing," Zhao Xiaojin, a senior official at the China Serospace Science and Technology, explained to China Central Television in 2018. "Chang'e 4 lunar probe will have huge improvements on its capabilities, because we have adopted new technologies and new products. For example, Chang'e 3 lunar probe could not work during the night, but Chang'e 4 lunar probe can do some measurement work at night."

The lander will carry a landing camera and topographic camera on the lander, similar to those found on CE-3. New instruments include:

- Lunar Dust Analyser, to study the physical characteristics of dust

- Electric Field Analyser to measure the magnitude of the electric field at various heights

- Plasma and Magnetic Field Observation Package

- Lunar Seismometer to study the interior of the moon

Another new feature is a Very Low Frequency (VLF) Radio Interferometer, which will be able to study the universe at extremely low wavelengths while the moon shields it from Earth's radio noise. This instrument will be helpful for future plans for putting a radio observatory on the moon, something often talked about but not yet planned by any country.

The lander will also carry payload created by students across China. A lunar mini biosphere experiment designed by 28 Chinese educational institutions led by Chongqing University was one of more than 200 submissions. The 7-lb. experiment will attempt to germinate seeds from potatoes and Arabidopsis, a small flowering plant related to cabbage and mustard. Silkworm eggs may also hitch a ride. The biosphere package will contain water, air and nutrients capable of sustaining the seeds and eggs within their protective dome. A tiny camera will allow researchers to observe the experiment back on Earth.

"Why potato and Arabidopsis? Because the growth period of Arabidopsis is short and convenient to observe. And potato could become a major source of food for future space travelers," Liu Hanlong, chief director of the experiment and vice president of Chongqing University, said in a statement. "Our experiment might help accumulate knowledge for building a lunar base and long-term residence on the moon."

The rover will carry three of the four instruments found on CE-3, including a panoramic camera, a ground-penetrating radar and an infrared spectrometer. It will also carry an Active Source Hammer for active source seismic experiments, and a second VLF radio receiver. The rover will also boast an energetic neutral atom analyzer.

"Obtaining the first direct measurements of the surface of the far side, as well as getting our first look at the low-frequency radio sky — key to understanding the early history of the universe — is potentially breakthrough science," Paul Spudis, a researcher at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas, wrote in an article for Air & Space magazine.

A two-step approach

One of the biggest reasons the far side has received so little exploration comes from geometry. Missions to the far side can't communicate through the massive body of the moon, so they have faced silence when out of sight of Earth. The launch of Queqiao should solve that problem.

Queqiao will sit at the Earth-moon Lagrange point 2 (L2), a special spot in the system where it will be able to see both worlds. L2 is a gravitationally stable spot located 40,000 miles (64,000 km) beyond the lunar far side. Its unique position will allow the satellite to relay messages from CE-4 to Earth, and from Earth to CE-4.

The relay satellite was carried to space atop a Long March 4C rocket on May 20, 2018, from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center in Sichuan Province, China.

Queqiao's orbit may prove a boon to missions beyond CE-4.

"We will make efforts to enable the relay satellite to work as long as possible to serve other probes, including those from other countries," Ye Peijian, a leading Chinese aerospace expert and consultant to China's lunar exploration program, said in a statement.

That includes China's planned Chang'e-5 lunar sample return mission, set to launch in 2019. Chinese officials have also declared their intent to put people on the surface of the moon before the end of the 2030s.

Additional resources

- The Planetary Society: Chang'e 4 relay satellite, Queqiao

- Air & Space: China's Journey to the Lunar Far Side: A Missed Opportunity?

Follow Nola Taylor Redd at @NolaTRedd, Facebook, or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky