Galactic Winds Halted Ancient Star Birth, But May Have Started It Elsewhere

Galactic winds that bowled through ancient galaxies and strangled star formation may not have been quite as destructive as previously thought: A new study shows these winds may have also created reservoirs of gas where star formation could continue.

The discovery came from the first-ever detection of carbon hydride (CH+) in ancient "starburst" galaxies, so-called because they experienced periods of rapid and extremely productive star formation. Those early stars then fertilized the universe with heavy elements necessary to create planets like Earth.

Using the powerful Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, the authors of the new study detected the chemical in five of six galaxies studied, according to a statement from European Southern Observatory, which manages ALMA. One of the galaxies, called the "Cosmic Eyelash," is located around 10 billion light-years away, which means the light left the galaxy when the universe was only about 3.7 billion years old.

"CH+ is a special molecule. It needs a lot of energy to form and is very reactive, which means its lifetime is very short and it can't be transported far," Martin Zwaan, an ESO astronomer and contributor of the study published in the journal Nature, said in the statement. "CH+ therefore traces how energy flows in the galaxies and their surroundings."

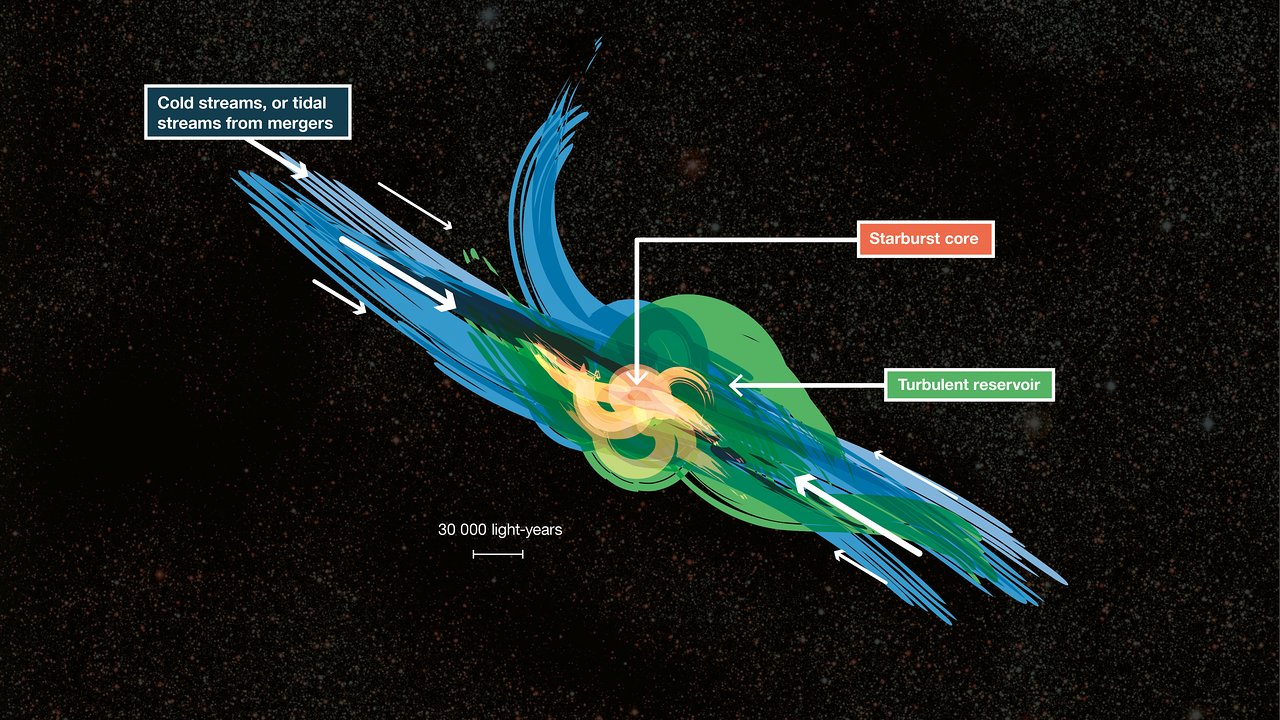

This chemical is produced where turbulent galactic winds dissipate, according to the statement. Powerful galactic winds are produced by very young massive stars as they form, so star-forming regions inside galaxies typically eject large quantities of material from the galaxy. These winds are therefore thought to halt star formation by starving these regions of gas.

But after studying the flow of CH+ in starburst galaxies, the researchers discovered that turbulent motions of these winds can create vast and cool reservoirs of gas extending more than 30,000 light-years from the galaxy's star-forming region. And it is these reservoirs of gas, trapped by the gravity of the galaxy, that continue to fuel star formation long after the original star-forming regions have halted production.

"With CH+, we learn that energy is stored within vast galaxy-sized winds and ends up as turbulent motions in previously unseen reservoirs of cold gas surrounding the galaxy," said lead author Edith Falgarone, of Ecole Normale Supérieure and Observatoire de Paris in France, in the statement. "Our results challenge the theory of galaxy evolution. By driving turbulence in the reservoirs, these galactic winds extend the starburst phase instead of quenching it."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The quantity of gas in these reservoirs couldn't have been solely supplied by galactic winds, however — the researchers suggest that the remaining gases are supplied by galactic mergers or from other streams of gas. But the fact that galactic winds seem to regulate the flow of material to star-forming regions is a "major step forward" in our understanding of how starburst galaxies work in the early universe, the researchers said.

Follow Ian O'Neill on Twitter @astroengine and at Astroengine.com. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Ian O'Neill is a media relations specialist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. Prior to joining JPL, he served as editor for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific‘s Mercury magazine and Mercury Online and contributed articles to a number of other publications, including Space.com, Space.com, Live Science, HISTORY.com, Scientific American. Ian holds a Ph.D in solar physics and a master's degree in planetary and space physics.