The Evolution of Solar Eclipse Photography in Photos

Introduction

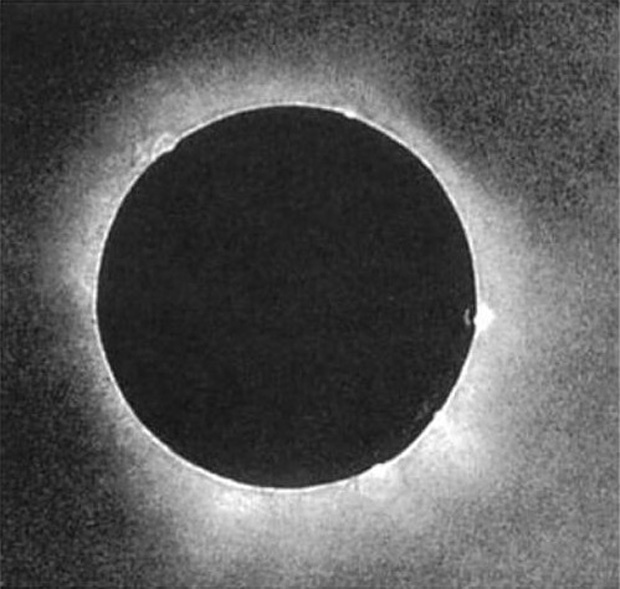

Solar eclipses have been happening on Earth since the solar system formed more than 4 billion years ago, and people have observed eclipses since ancient times. But it wasn't until the mid-19th century that people figured out how to photograph solar eclipses. The first photo of a total solar eclipse, shown here, was a daguerreotype by the Prussian photographer Johann Julius Friedrich Berkowski.

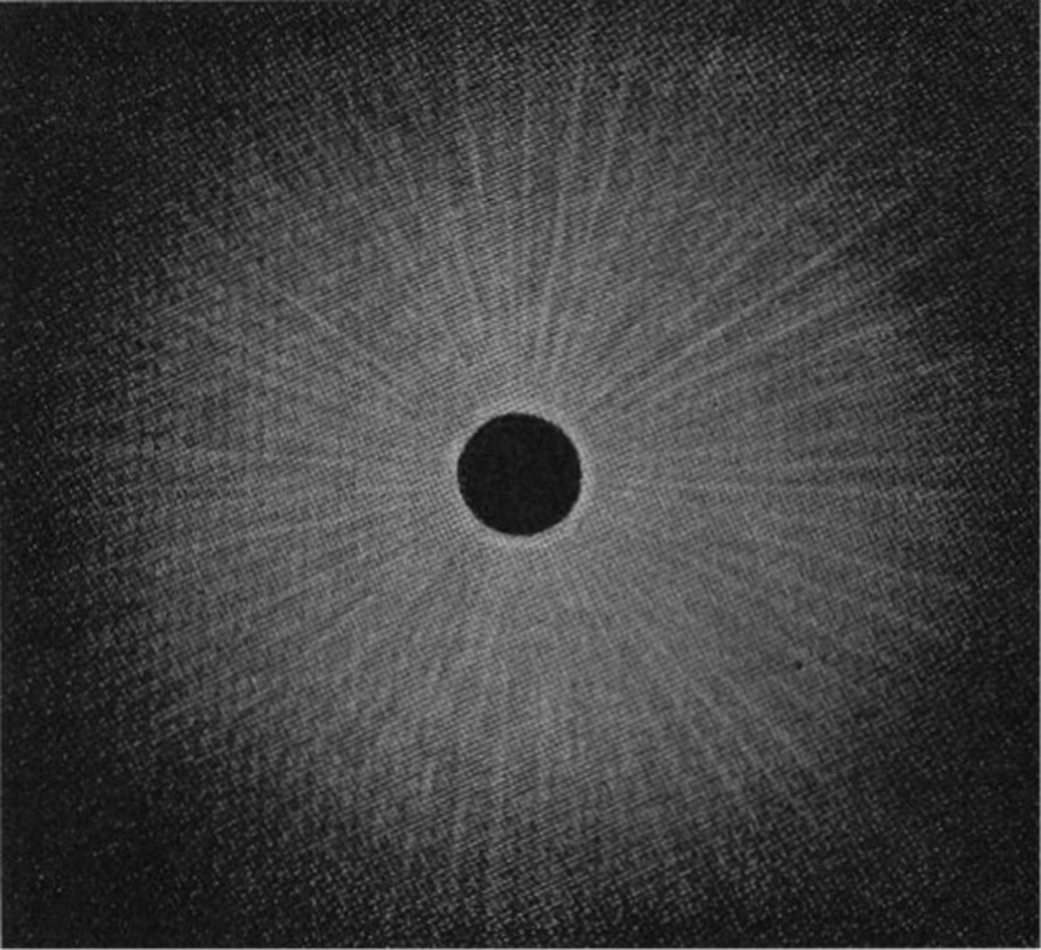

Sketching the Sun

Before there were photos of solar eclipses, the only way to record what they looked like was by swiftly sketching them. Totality only lasts a few minutes, so astronomers had limited time to draw what they saw. This sketch by Spanish astronomer José Joaquin de Ferrer depicts the sun's corona during a total solar eclipse on June 16, 1806. [What Were the First Records of Solar Eclipses?]

Measuring the Sun

During the total solar eclipse of May 28, 1900, American astronomer Samuel Pierpont Langley used an invention called a Bolometer and a rotating mirror called a coelostat to measure the sun's thermal radiation and the spectrum of light emitted by the corona. He went to Wadesboro, North Carolina with a large group of scientists from the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Washington, D.C. to watch the eclipse from the best possible location.

Glass Plates

Another scientist with the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, Thomas Smillie, photographed the eclipse of May 28, 1900 using seven different telescopes. He created eight glass-plate negatives and successfully captured the sun's corona.

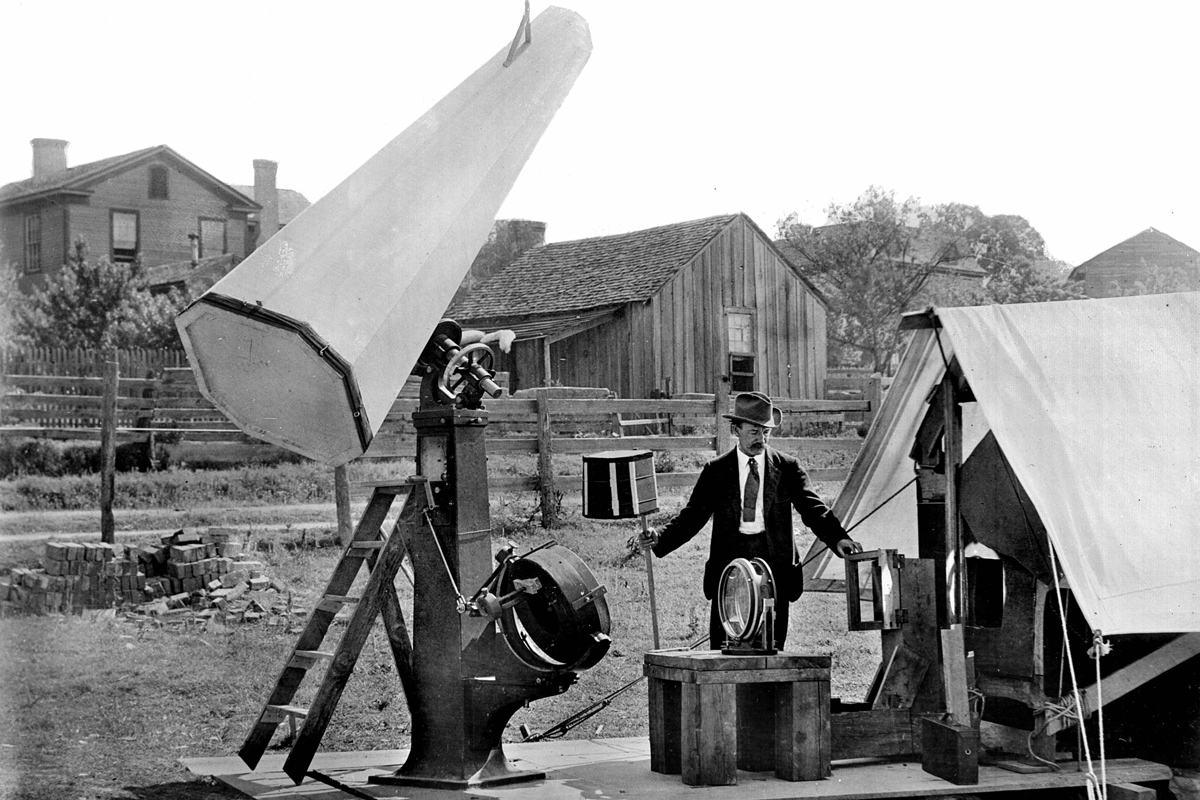

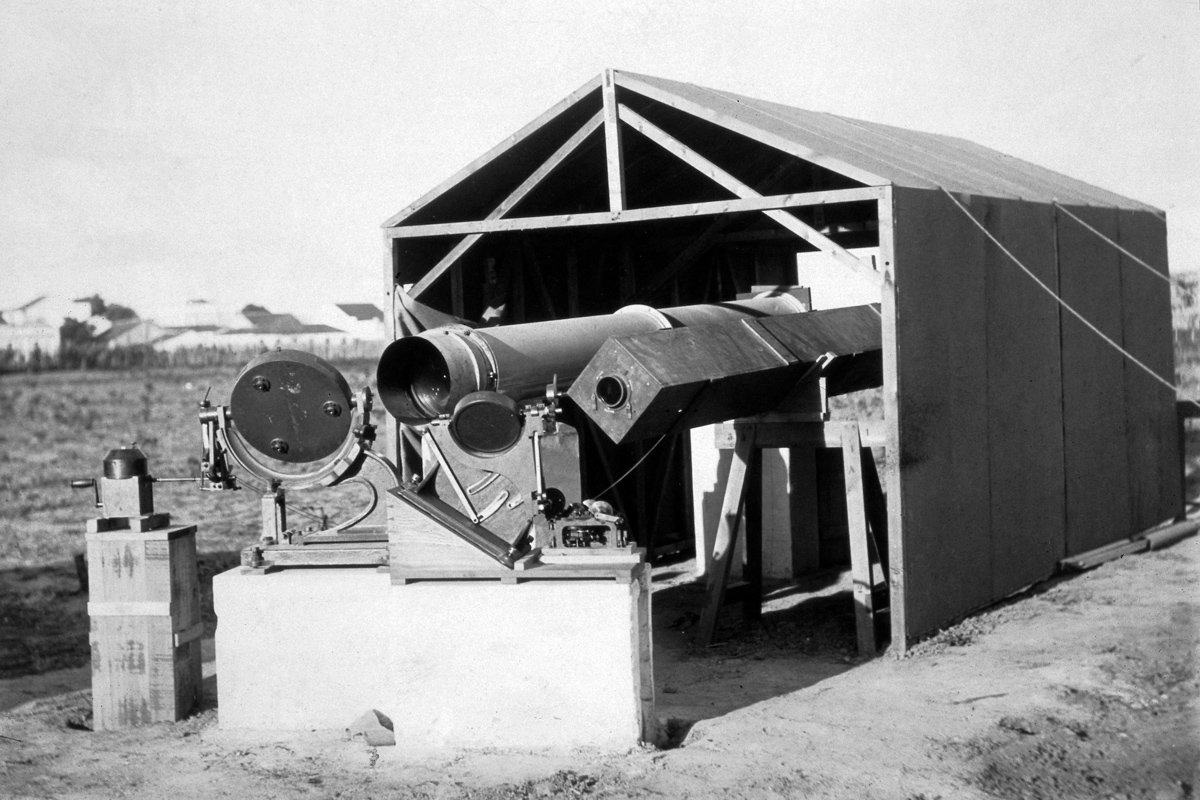

Heliostats

This is the equipment that British astronomers used to observe total solar eclipse on 29 May 1919 from Sobral, Brazil. Sir Arthur Eddington organized an expedition to try and test Einstein's theory of relativity. His team used two heliostats, or rotating mirrors, to direct images of the eclipsed sun into a pair of horizontal telescopes.

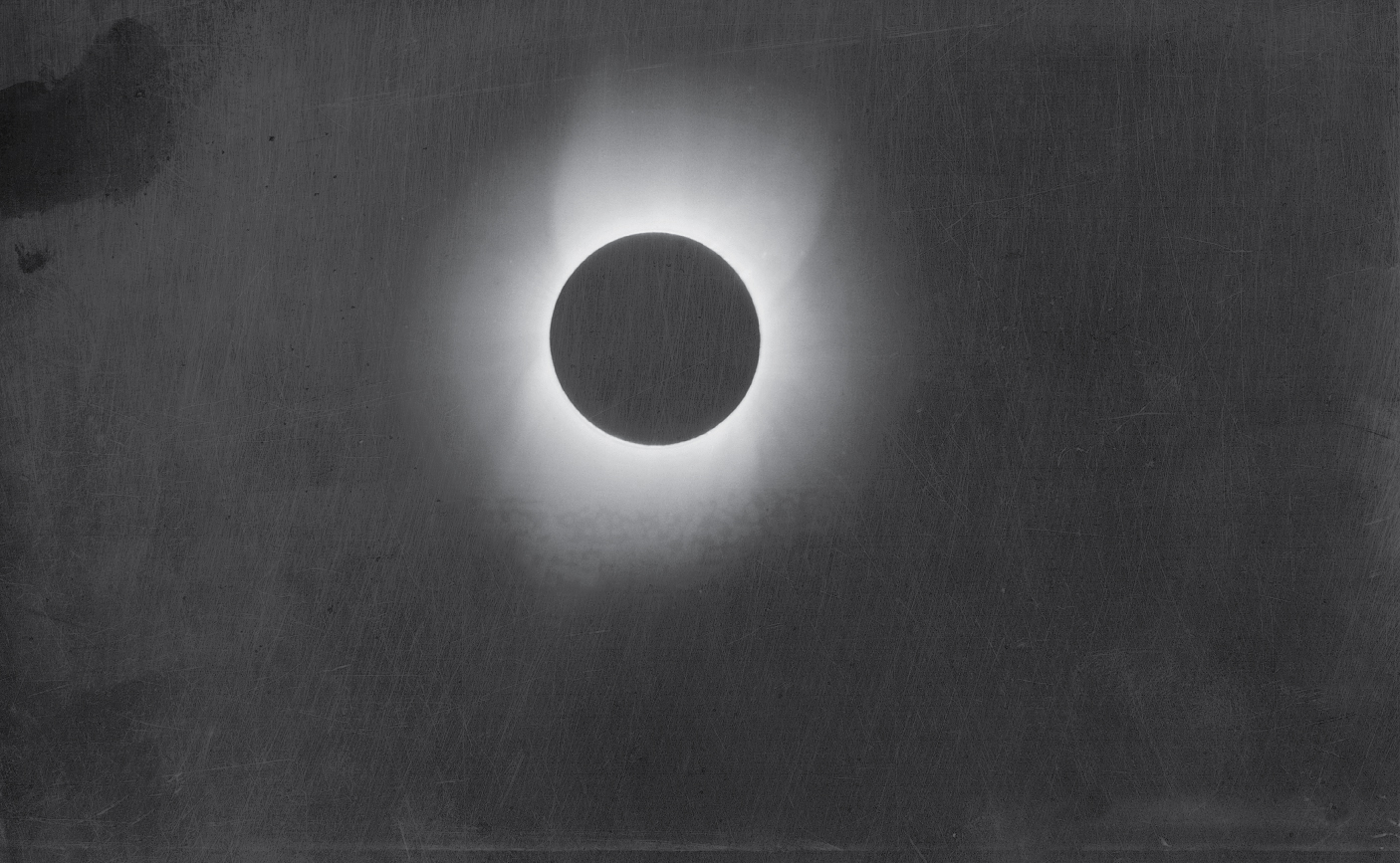

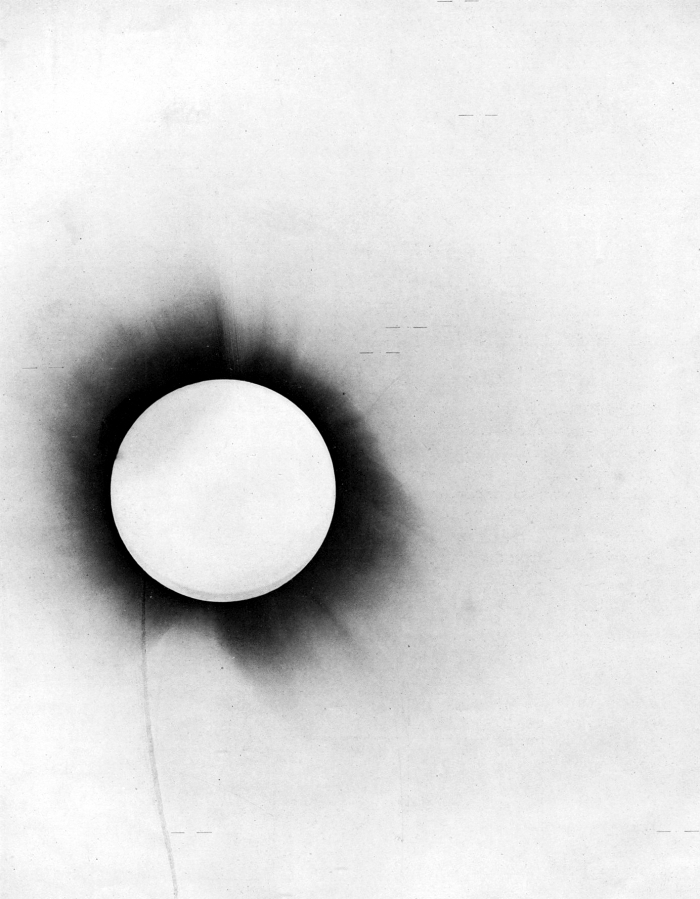

Negatives

Sir Arthur Eddington produced this negative of the 1919 total solar eclipse during his expedition in Sobral, Brazil. He used a 4-inch (100-mm) astrographic telescope to capture the image on a photographic plate about the size of a sheet of printer paper.

The Astrograph

Known as an astrographic camera, this contraption was used by German scientists to once again test Einstein's theory of relativity during a total solar eclipse on Jan. 14, 1926. Astrophotographers still use astrographs to this day, but they have become smaller and more technologically advanced over time.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Totality

Astronomers at the Harvard College Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts captured this image of a total solar eclipse on Jan. 14, 1926.

Casual Eclipse-Gazers

An amateur astronomer photographs an eclipse of the sun with a telescope in the middle of a road and a pipe hanging from his mouth on June 19, 1936.

Digital Photos

Following the invention of the electronic camera in 1975 and the DSLR (digital single-lens reflex) camera in 1986, taking pictures of solar eclipses has gotten much easier. Now even amateur astronomers can snap amazing eclipse photos with telescopic cameras, and you can even watch the eclipse happen on your computer screen instead of gazing up at the sun.

Cell Phone Shots

As technology has become smaller and more portable, people can now fit all the necessary eclipse photography gear into their pant pockets. To take pictures of the eclipse with your phone, all you need is a solar filter. In this photo, a skywatcher uses a welding mask as a solar filter.

Hanneke Weitering is a multimedia journalist in the Pacific Northwest reporting on the future of aviation at FutureFlight.aero and Aviation International News and was previously the Editor for Spaceflight and Astronomy news here at Space.com. As an editor with over 10 years of experience in science journalism she has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy. She currently lives in Seattle, home of the Space Needle, with her cat and two snakes. In her spare time, Hanneke enjoys exploring the Rocky Mountains, basking in nature and looking for dark skies to gaze at the cosmos.