Going Bananas: The Real Story of Kepler, Copernicus and the Church

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Paul Sutter is an astrophysicist at The Ohio State University and the chief scientist at COSI Science Center. Sutter is also host of Ask a Spaceman, RealSpace, and COSI Science Now.

We all know the story. Centuries ago, everyone in the Western world believed that the Earth was the center of the universe, with the sun, the stars, the planets and everything else revolving around it. That model sort of stunk at predicting the motions of the other planets, so countless numbers of "epicycles," or circles-within-circles, were added to their orbital paths to explain the data. OK, whatever.

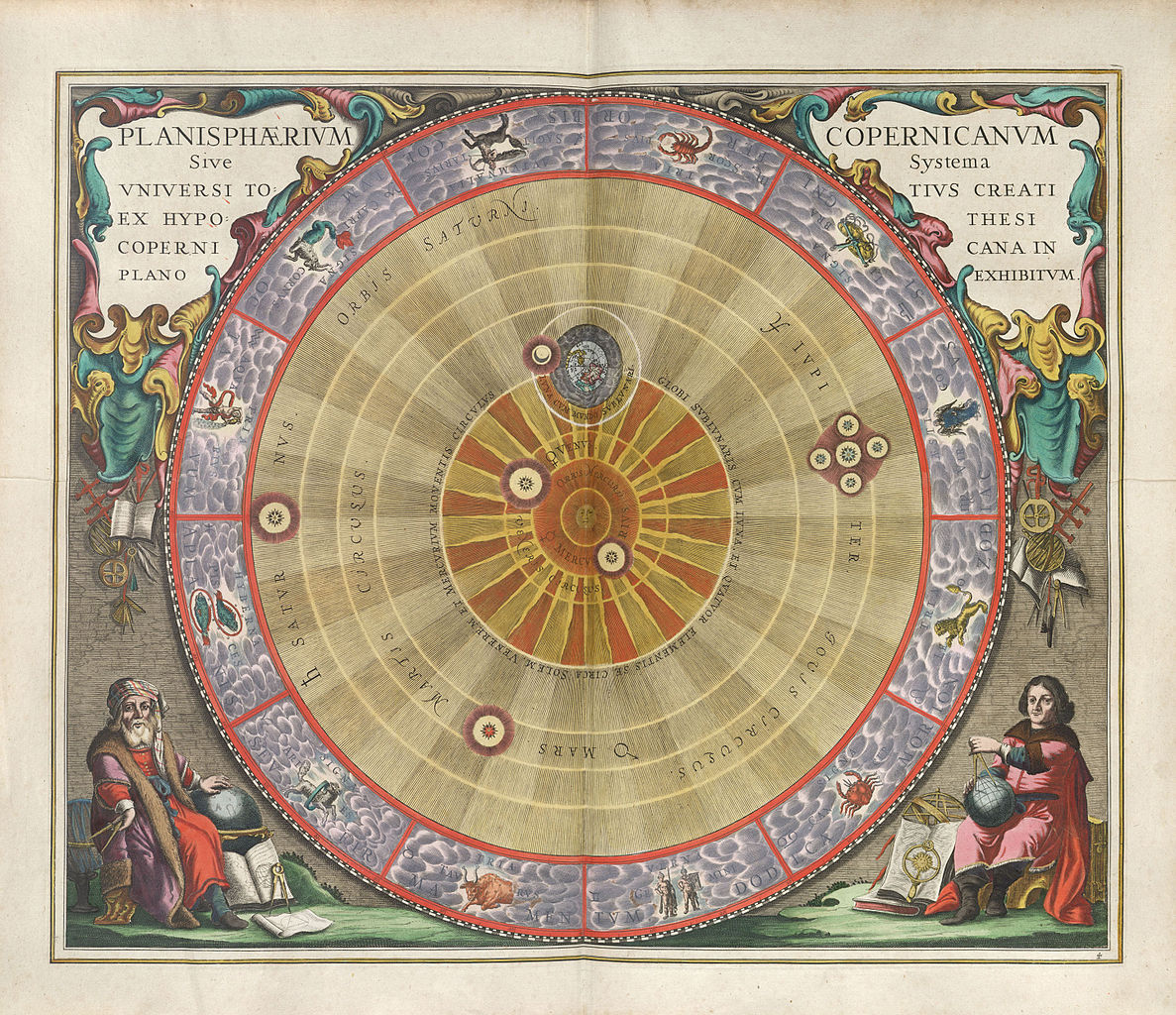

Things were going along fine until Nicolaus Copernicus decided to try Science and put the sun at the center of the solar system. Wow, everything was awesome! But the Catholic Church hated it. Then Johannes Kepler found that planets don't move in circles, but in ellipses. And his model was super-accurate. Another point for Science! Take that, Church.

Article continues belowThen Galileo Galilei started barking up the papal tree and everyone went nuts. Lots of arguing and heretic-burning ensued but eventually Science won. [History's Most Famous Astronomers]

That's the basic story many people know about the battle between Science and the Church over very early models of the solar system. But there are nuances to this story that often get lost in the telling. A full untangling of truth from fiction would require a whole book, but for now, I’m going to take a closer look at the work of Johannes Kepler, in order to show that the real story isn’t so straight-and-narrow.

All mixed up

In modern times we neatly separate science, philosophy and religion into their nice tidy little boxes, and get annoyed when members of one box start talking about the contents of another domain. And we view the history of science as proto-scientists fighting against the Church to leave them in peace and let them do their science-y thing

However, there are two important things to remember when looking at the early history of science around the time of Copernicus and Kepler:

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

1) What we now call science, philosophy and theology were all mixed up together.

2) Early (proto-)scientists made claims and arguments that would sound totally bananas today.

I'll leave Copernicus' motivations to another article, but he did indeed publish a book in 1543 detailing his new cosmology with the sun at the center of the universe. While it did have some advantages over the en vogue geocentric model (like neatly explaining the precession of planetary orbits and requiring fewer circles-within-circles), it did have weaknesses (how, exactly, does something like the Earth move?), and the reaction among the literate community — including the Catholic clergy — was neither hostile nor supportive. At the time, the cosmology of Copernicus simply wasn't very compelling.

A generation later, Kepler penned a work in defense of the Copernican model, but not on physical or mathematical grounds — Kepler's argument was religious. He said that since the son of God was at the center of the Christian faith, the sun ought to be at the center of the universe. Ergo, heliocentrism.

Yeah, I told you: bananas.

Secrets in the sky

Kepler's day job was as the court astrologer for the Holy Roman Emperor. Yes: astrologer. Horoscopes and stuff. And he was way more obsessed with numerology than he should have been.

Or maybe not, since that obsession led him to develop his now-famous three laws. Convinced for quasi-spiritual reasons that the sun was at the center of the universe, he labored for years, poring over tables and tables of handwritten charts detailing the precise locations of the planets.

Kepler wasn’t just looking for a handy fitting formula; he was searching for signs of the divine. He was convinced that the heavens, being naturally closer to God, contained a sort of perfection not seen on Earth since the Garden of Eden. What's more, if he could deduce the divine geometry of the heavens, he could look for similarities here on Earth to help predict the future.

Here's an example. After years of continual frustration from trying ever-more Byzantine (and ever-more unsatisfactory) equations to fit the motions of the planets, Kepler gave the simple ellipse a shot. Besides working really, really well, Kepler was convinced he got it right because of the relationship between the motions of the planets and music.

Here we are again: bananas.

Music of the spheres

Kepler found that the planets move in ellipses, not circles, around the sun. He also found that when the planets are closer to the sun, they move faster than when they're farther away.

When it comes to the Earth, the ratio between its fastest speed and slowest speed reduces to 16/15, which is the same ratio between the notes fa and mi. Needless to say, Kepler thought this was fantastically important:

“The Earth sings Mi, Fa, Mi: you may infer even from the syllables that in this our home misery and famine hold sway.”

To Kepler, this was the clincher. Why were the heavens so perfect but the Earth so full of wretchedness? The music of the spheres tells us - it fit so perfectly! His new system wasn't just a mathematical convenience, but a window into the mind of God and the hidden order of the universe.

Universal harmony

Kepler was so convinced that there was some sort of hidden order in the heavens that he dug even deeper. Surely there was something that could unlock those juicy divine mysteries. After more years of laborious study, he found it: the square of a planet's orbital period (the time it takes to get around the sun) is directly proportional to the cube of its semimajor axis (the planet's farthest distance from the sun), and that proportion is the same for all the planets.

Why the square of the orbital period? Why not the semimajor axis to the fourth power? Kepler didn't know and (probably) didn't care. He found a universal constant, a single number that tied together the motions of all the planets — and the Earth.

Here, at least, was the divine music — and numerology — Kepler sought after years of labor. His model of the universe united the earthly and celestial realms in (literal) harmony, it found beautiful and simple geometric elegance in the motions of the planets, and his simple formulas for predicting planetary positions made for excellent horoscopes.

Learn more by listening to the episode "Why are Kepler's Laws important?" on the Ask A Spaceman podcast, available on iTunes and on the web at http://www.askaspaceman.com. Thanks to @sconlineteacher for the questions that led to this piece! Ask your own question on Twitter using #AskASpaceman or by following Paul @PaulMattSutter and facebook.com/PaulMattSutter.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University, host of Ask a Spaceman, and author of How to Die in Space.