Royal Observatory Greenwich: The birthplace of modern astronomy turns 350

That's a lot of standard candles.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

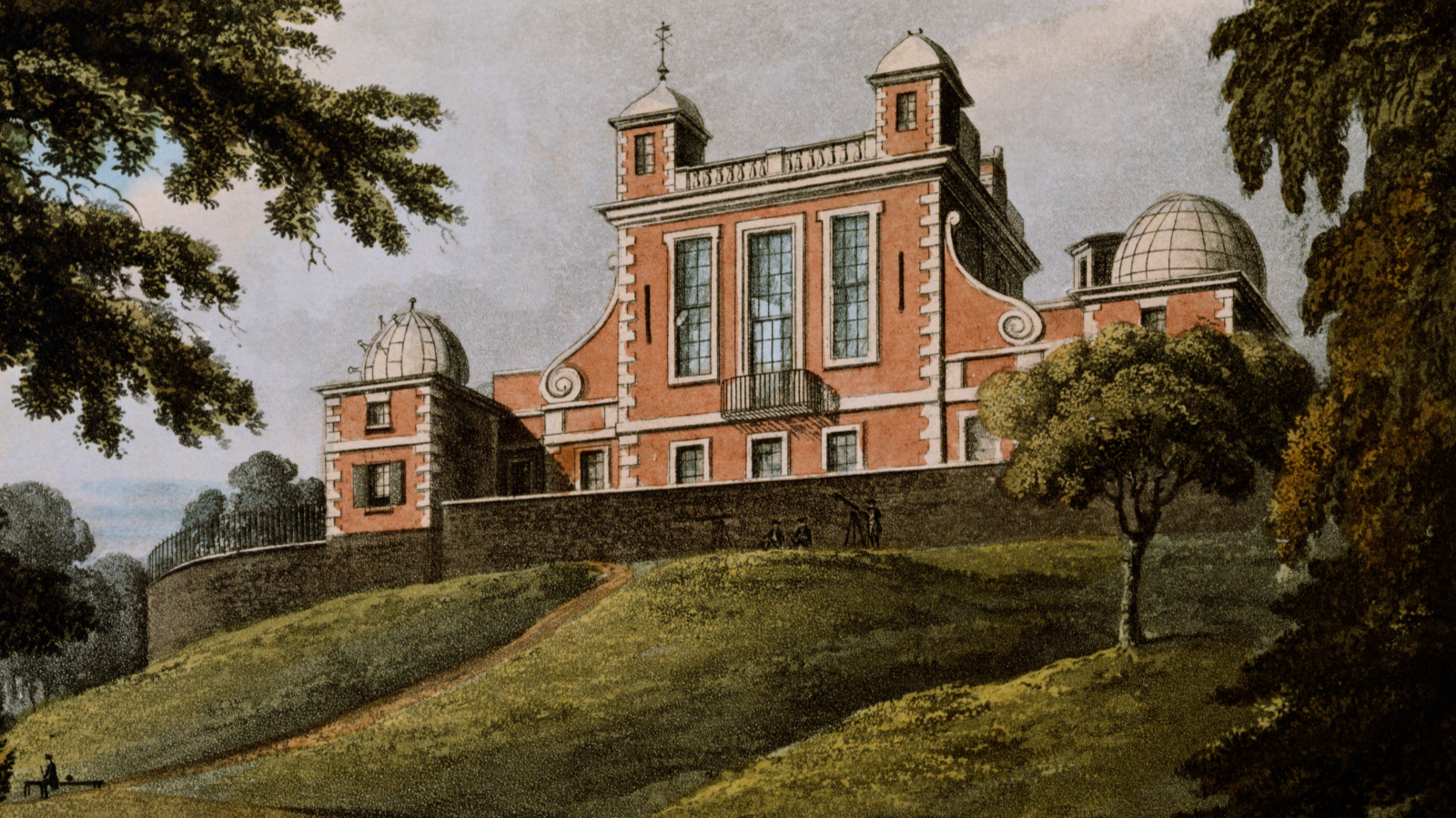

June 22 marks the 350th anniversary of the Royal Observatory Greenwich, the home of the historic Prime Meridian that is considered by many to be the birthplace of modern astronomy. To celebrate, we're taking a look back on how the famous site became the epicenter of astronomical research, timekeeping and navigation, while highlighting how its purpose has evolved over time.

The Royal Observatory's story began in 1675, when King Charles II of England decided that a purpose-built scientific institution was needed to solve a centuries old question - how can sailors navigate safely at sea?

In the 1600s, seafaring was the only way for nations to communicate and assert influence over one another, and so finding an answer to the question was vital for everything from trade, to diplomacy, exploration and warfare. Sailors and astronomers had long since figured out how to establish their latitude at sea, but despite centuries of seafaring, we had yet to find a system for determining longitude.

The newly minted Royal Observatory's main purpose was to find a way to accurately and consistently measure a sailor's longitude, which in turn would allow a ship's captain to navigate the vast oceans separating the continents. To that end, King Charles II appointed John Flamsteed as his 'Astronomical Observator' - later to be known as 'Astronomer Royal' - and tasked architect Christopher Wren to design the initial structure that the institution we see today grew up around.

Generations of astronomers, scientists and horologists bent their expertise to solving the riddle, but it would be many decades before the Royal Observatory's founding mission was completed. Since its inception, astronomers had busied themselves tracking the apparent movements of the stars, moon and planets relative to an imaginary line running north to south through the observatory, known as a 'meridian'.

These observations led to the creation of the first Nautical Almanac - a collection of tables that predicted the position of the moon and stars throughout the year - along with a handbook explaining how to mathematically determine longitude at sea, according to the Royal Observatory Greenwich website. By the year 1770, the English horologist John Harrison had also developed a complex timepiece that, unlike the pendulum-based clocks at the time, worked aboard a moving ship, giving sailors two ways to determine longitude!

By the 1880s two-thirds of the world's ships were navigating with maps that used the Greenwich meridian as a reference line. As such, when a conference was held in 1884 to decide the world's first global, or 'Prime Meridian', Greenwich was the obvious, if not uncontested choice.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The invention of railway travel also necessitated the establishment of a unified time zone, which was provided by the Royal Observatory and adopted by the railway companies. This new 'Greenwich Mean Time' (GMT) quickly spread and was adopted during the 1884 Meridian Conference as the new global time zone system, making the observatory the global reference center for time, navigation and astronomy.

Changing times at the Royal Observatory Greenwich

As centuries passed, generations of Astronomers Royal came and went, each leaving their own scientific achievements and personal marks on the historic site, which grew larger as new facilities and buildings sprung up around the original Wren-designed Flamsteed House.

With the quest for longitude over, the observatory explored other avenues of astronomy, such as tracking Earth's magnetic field, viewing planetary transits and characterizing binary star systems. This was done with the aid of powerful new equipment, such as the Great Equatorial Telescope - a 28-feet-long (8.5 metres) refracting telescope that boasted a 28-inch aperture, which had to be housed in a vast circular shell known as the 'Onion Dome' when installed in 1893.

The observatory's practices and functions were also heavily influenced by cultural and technological paradigm shifts - and some personal grudges - that were taking root in the wider world beyond.

For example, the 1890s saw the Royal Observatory hire women for the first time, who worked for a pitiful wage as 'computers' to examine and refine observational data. Among their ranks was the famous science communicator and astronomer Annie Maunder, who advanced the scientific community's understanding of our parent star by observing the shifting sizes and positions of sunspots.

Sadly, social convention dictated that Maunder resign her position upon marrying her husband and colleague Edward Walter Maunder in 1895. However, the couple would go on to continue their work away from the observatory, writing books and chartering expeditions to capture images of the sun's atmosphere during solar eclipse events. The Maunders also created the famous 'butterfly diagram', which used over a decade of observational data to visualize the 'flapping' butterfly-wing-like disposition of sunspots that occurs as the sun progresses through its 11-year activity cycle.

The Royal Observatory has also faced its share of conflict, intrigue and danger since its inception. Vitriolic rivalries have blossomed between its astronomers and prominent scientific figures. John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal, struck up a strong rivalry with Sir Isaac Newton, who hoped to use Flamsteed's star charts to refine his theories. Flamsteed had refused to release his star charts until he was certain the information within was correct, which led a frustrated Newton to publish an imperfect version of the work without the Astronomer Royal's permission.

The site itself has also weathered physical threats, including an attempted anarchist bomb attack in 1894. World War 2 also saw a V1 flying bomb detonate nearby, shredding entire sections of the famous 'Onion Dome'. Thankfully, the telescope itself had been deconstructed and moved away from the observatory to safeguard it from the perils of war.

In the wake of the second World War, the relentless creep of light pollution, smog from nearby London and the vibrations and magnetic interference from railway lines had rendered Greenwich an unfeasible location for delicate astronomical observation.

In 1948, the telescopes and astronomers of Greenwich - including the vast bulk of the Great Equatorial Telescope - began relocating to the village of Herstmonceux some 60 miles from where Flamsteed had set the foundation stone for the first Royal Observatory in 1675. The Great Equatorial Telescope would eventually return to the Royal Observatory Greenwich in 1971, where it remains to this day.

A new era for the Royal Observatory Greenwich

In the modern era, the Royal Observatory Greenwich serves as an invaluable historical site that serves as both a museum and a venue for science communication geared towards engaging and inspiring the next generation of astronomers.

Visitors are free to follow in the footsteps of the Astronomers Royal and tread the same Wren-designed rooms that were paced by the likes of Sir Isaac Newton. It represents a potent mixture of the old and the new, featuring the only planetarium show in London alongside the historic Prime Meridian and detailed replicas of the timepieces used to ensure safe navigation by sea.

"Founded in 1675, the Observatory was established to aid navigation through astronomical observations and timekeeping, beginning with John Flamsteed's meticulous project to catalogue 3,000 stars," said Royal Observatory Greenwich History of Science assistant curator Daisy Chamberlain to Space.com. "Since then, the work of the Observatory expanded to include studies of magnetic variation, meteorology, and chronometer testing for the Navy."

"Today, we share the wonders of time and space with our visitors through a number of fascinating permanent galleries, talks, tours, and heritage activities."

On clear nights you can still find astronomers plying their trade at the historic site, using the Annie Maunder Astrographic Telescope — consisting of a vast Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope alongside a smaller refractor — to capture transit data, alongside stunning views of the cosmos.

"The Annie Maunder Astrographic Telescope has given us the privilege of keeping practical astronomy alive and well at the observatory, using modern technology that our predecessors in previous centuries could only dream of," explained Jake Foster, an astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich to Space.com. "With astrophotography and livestreams of astronomical events, we aim to bring the sights of the Universe down to Earth for all to enjoy."

"Even under the modern-day light-polluted skies of London, there's so much to see! We hope that the Royal Observatory astronomers of days gone by would approve of our efforts."

Be sure to check out the Royal Observatory Greenwich website to stay up to date with talks, tours and events to celebrate the 350th anniversary of the historic site.

Anthony Wood joined Space.com in April 2025 after contributing articles to outlets including IGN, New Atlas and Gizmodo. He has a passion for the night sky, science, Hideo Kojima, and human space exploration, and can’t wait for the day when astronauts once again set foot on the moon.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.