Philae Lander's Grave on Comet Found at Last After Nearly 2-Year Search

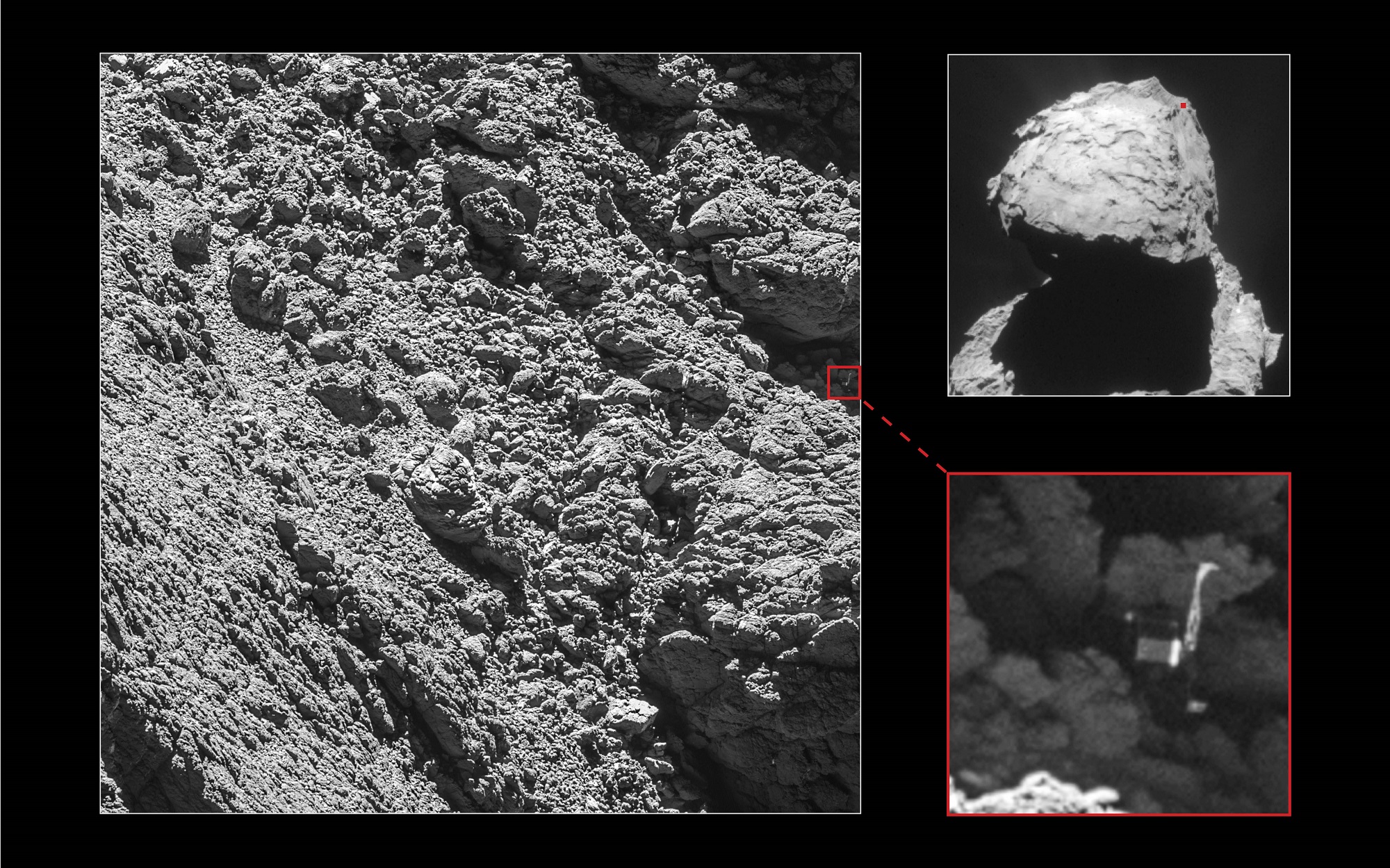

The final resting place of the European comet lander Philae is a mystery no more. After nearly two years of searching, the lander's shadowy grave on Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko has been found in images from its mothership Rosetta.

The European Space Agency's Philae lander touched down on Comet 67P (as scientists call it) in Nov. 12, 2014, but its final location was uncertain due to the probe's rough, bouncy landing. News of Philae's discovery comes just weeks before Rosetta — low on solar power as the comet moves away from the sun — is set for a dramatic touchdown itself on 67P's surface to end the mission. In a statement today (Sept. 5), ESA officials expressed marvel that they found Philae at almost the last minute.

"With only a month left of the Rosetta mission, we are so happy to have finally imaged Philae, and to see it in such amazing detail," said Cecilia Tubiana of the OSIRIS narrow-angle camera team, in a statement. She was the first person to see the images when they were downlinked from Rosetta yesterday. [Philae's Rough Comet Landing Explained (Infographic)]

Philae's landing on Nov. 12, 2014 did not go as expected. After anchoring harpoons on the spacecraft failed to deploy, it made a triple touchdown before skidding to a stop in a shadowy zone.

The solar-powered lander was forced to rely on batteries to do its work. It sent just 60 hours of data from the surface, but made several findings in that short time – including detecting organics on 67P. Philae only made intermittent contact with Rosetta before the lander's mission was declared over this July, a year after Philae's last signal was detected.

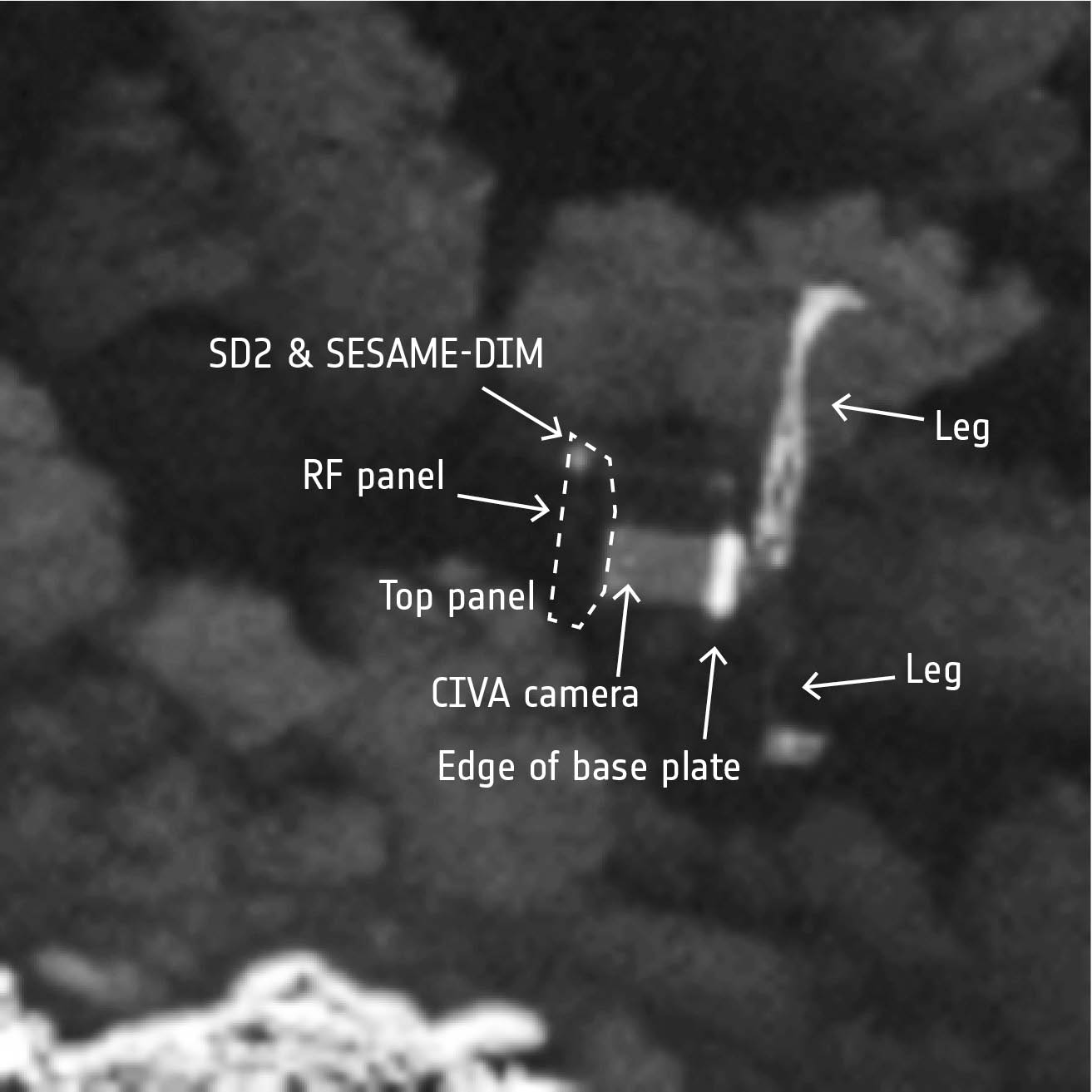

The new pictures show why it was so hard for Rosetta to get in touch after Philae's landing. The lander is resting on its side in a crevice, with two legs plainly visible in high-resolution imagery.

Rosetta began its search shortly after Philae's landing. ESA officials said that radio ranging data showed a suggested search area of several tens of meters. Rosetta imaged several possible objects. The team eliminated all but one target after the imagery was analyzed, among other techniques.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, a closer look had to wait until Rosetta shortened its orbit above the comet, towards the end of the mission. Confirmation finally came in images from Sept. 2, when Rosetta was just 1.7 miles (2.7 kilometers) above Philae on the surface.

A labelled picture from ESA not only reveals Philae's legs, but also some of its instruments and panels. Closer images will be possible when Rosetta descends towards the comet, ESA officials added.

"This wonderful news means that we now have the missing 'ground-truth' information needed to put Philae’s three days of science into proper context, now that we know where that ground actually is," said Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist, in the same statement.

Rosetta – which isn't designed to land on the comet – will nevertheless touch down on Sept. 30 in 67P's light gravity. During descent, ESA plans to look at zones such as open pits in the Ma'at region, which could reveal more about the comet's insides.

The orbiter's daring end is similar to NASA's NEAR Shoemaker descent on asteroid 433 Eros on Feb. 12, 2001. Like Rosetta, Shoemaker was not designed to land, but did so safely. While no images were sent after landing, the spacecraft continued sending data for two weeks after touching down.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebookand Google+.Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.