'Into the Black': Book Recounts Untold Story of 1st Space Shuttle Flight

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

On April 12, 1981, NASA astronauts John Young and Bob Crippen climbed aboard the space shuttle Columbia for a mission unprecedented in human history. For the first time, a crewed spacecraft was going to be tested with humans aboard on its inaugural flight. And this wasn't just any spacecraft — the enormous delta-wing orbiter was utterly unlike any of the capsules that humans had flown since Yuri Gagarin first flew to space exactly 20 years earlier.

The launch of Columbia appeared to go perfectly. But, after the astronauts opened the payload bay doors on orbit, they spotted missing protective thermal tiles at the aft end of the orbiter. The question was whether other tiles had been knocked off on the crucial underside of the ship. If they had been, the shuttle could burn up during re-entry.

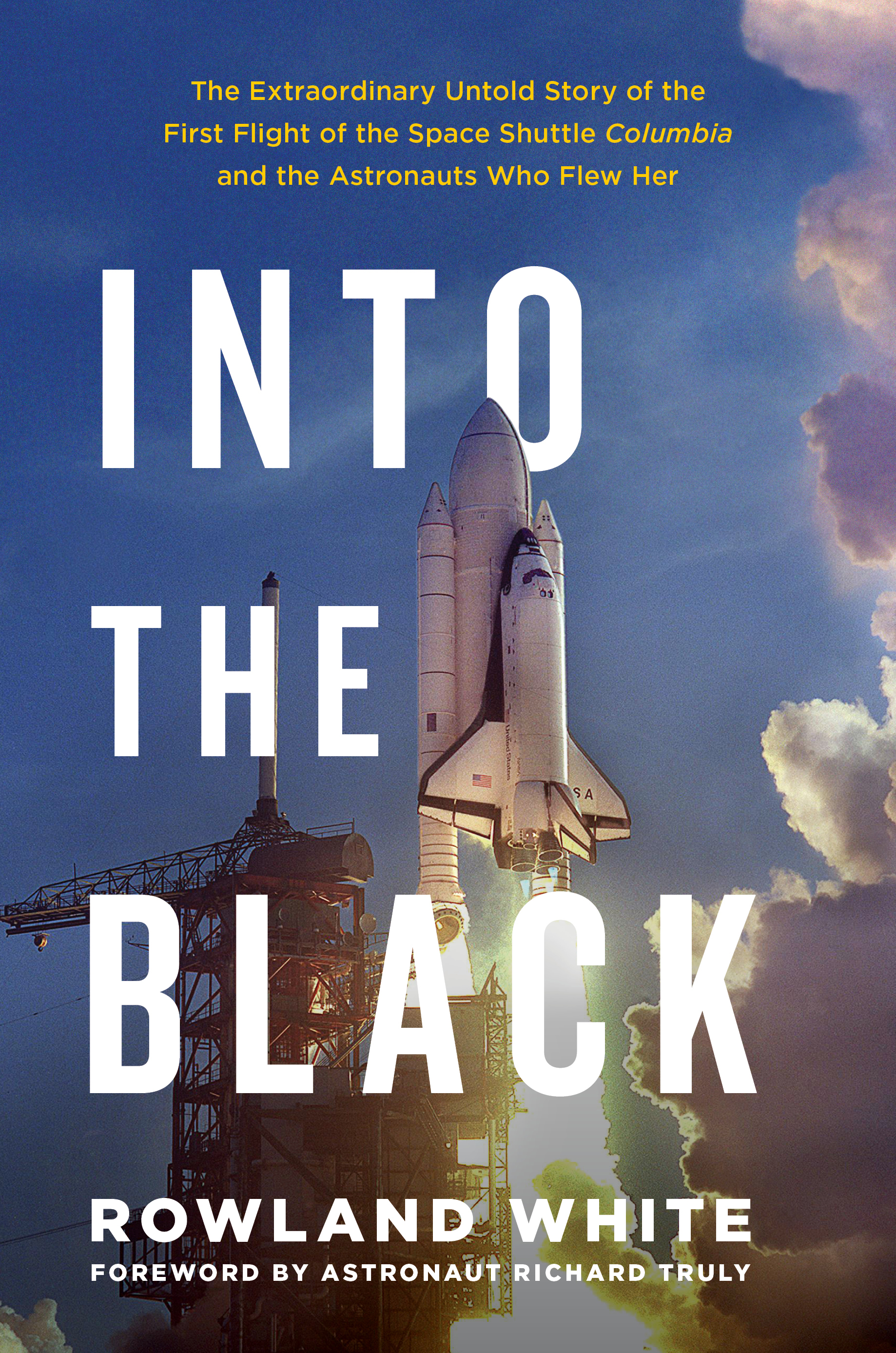

The secret effort by NASA and the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) to find the answer to this question using spy satellites is recounted in Rowland White's new book, "Into the Black: The Extraordinary Untold Story of the First Flight of the Space Shuttle Columbia and the Astronauts Who Flew Her" (Touchstone, 2016). [STS-1: The First Space Shuttle Flight in Photos]

Released in April, in time for the 35th anniversary of Columbia's first flight, the book is much more than a recounting of the 2.5-day flight. White tells the story of how a group of astronauts from the U.S. Air Force's canceled Manned Orbiting Laboratory helped form the core of the team that got the shuttle to orbit. The author also follows the orbiter's difficult development history through the 1970s, particularly the fragile thermal protection tiles.

Space.com recently spoke with White about the book.

Space.com: What made you pursue this project?

Rowland White: I was born in 1970 and grew up as an aviation nut. Of course, the last time that the American astronauts launched in the '70s was in 1975 for Apollo Soyuz. So I sort of missed out on the excitement of the whole Apollo program. So when the shuttle launched in 1981, it really captured my imagination for two reasons, really. One, it was the first time that I had been old enough to really enjoy the launch of American astronauts. The second reason was that here was a spacecraft with wings, it wasn't one of sorts of spidery tin cans that had taken astronauts to the moon. It was a sort of spacecraft out of the pages of science fiction, designed to carry a crew of up to seven or eight people on a mission of a couple of weeks, before swooping down and landing at an airfield ready to fly again. It just felt like it was the machine that was almost designed to capture my imagination in a way that with Apollo I sort of missed out on.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Space.com: Why did you focus on the first mission as opposed to a broader kind of book that might have covered the whole program?

White: I hope that through the sort of prism of that first flight I'd be able to draw in the various strands of the shuttle's development, the story of the astronauts, the story of the relationship between NASA and the military. And have at the heart of the story a sort of single focal point that would mean I can build a narrative that felt like a thriller, although I hope that all of the history and the science was rigorous and accurate. But I wanted to try to build a narrative that really had readers ripping through the pages to a sort of climax that felt like the last act of a big movie. In order to do that, you've really got to have a focal point, you have to have characters that readers can invest in, and you've got to have those characters in a situation that involves a measure of jeopardy and uncertainty. And in first flight of the shuttle where so much was unknown despite all the testing, despite all the research. So much was unknown about how she would perform in reality, that you had all of that. In John Young and Bob Crippen, you had a pair of really interesting characters flying together on board the shuttle's first flight.

Space.com: How would you describe their differences and their characters and how they meshed together?

White: They were to an extent a different generation. John Young had come up through Gemini and Apollo. He was very much a contemporary; obviously he first flew with Gus Grissom, a contemporary of Neil Armstrong. He sort of conducted himself in a different way to Bob Crippen, who always sort of seemed looser, more at ease, a sort of a cooler character somehow. I really came to appreciate and like enormously John Young. First of all, it's impossible to question either his experience or his competence or his intelligence, but I really came to value his incredibly dry and very funny sense of humor as well. I think he had a sort of perfect sense of comic timing. John Young, when he was asked whether or not he was nervous about the first flight of Columbia, said anyone who climbs aboard the biggest hydrogen oxygen explosion and isn't a little nervous doesn't appreciate the gravity of the situation they're in. He was a funny guy.

Bob Crippen obviously came to the shuttle along a very different path. Throughout the '60s he was kind of immersed in the black world of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory project. He had come through Chuck Yeager's Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards. And then he was part of the MOL program for the whole of the '60s. He was a refugee from that program in 1969. He and Richard Truly and Gordon Fullerton and a handful of others were taken on by NASA in 1969 kind of rather against Deke Slayton's better judgment because it was reckoned that NASA would need Air Force support for the shuttle, and that taking on some of these refugee military astronauts might win favors from the Air Force.

Space.com: How many of these guys did you get to talk to? Did you get to talk to Young and Crippen?

White: I spoke to Crip and Dick Truly, Fred Haise. I spoke to Joe Engle. I spoke to a handful of the TFNG's [Thirty-Five New Guys] like Jon McBride and Dan Brandenstein, Rick Hauck. I spoke to George Abbey. I spoke to Tom Moser, who was head of the structural mechanics division, Hugh Harris, who was the public affairs officer. As well as meeting and talking to some of the astronauts and engineers and administrators involved, I also made great use of the incredible JSC (Johnson Space Center) oral history program. The archive there is extraordinary, and I really went through that with a fine-tooth comb.

Space.com: Did John Young not want to speak?

White: John Young was the only member of that first primary crew and reserve crew that I didn't get to talk to, and it was a great shame. As I understand it, he's not in the best of health. Thankfully, he's published an autobiography and that alongside of a lot of interviews with him, film footage of him, and written material, allowed me, I think, to certainly get a feel for him.

Space.com: Did you pursue any big mysteries in the book?

White: We know that a request of the Air Force for photographs of Columbia on orbit in 2003 was rescinded by Mission Control. So I asked one of the astronauts, in 1981 when you knew that there was damage to the heat shield, did NASA ask the Air Force for pictures? And he sort of chuckled to himself and said, "You know, that's a great story and I can't tell you a thing about it."

That, of course, that was the moment when I thought, that's the story I want to tell. Because that's the one which no one knows. That became the ambition from that point […] to try to bring that story to light. And it remained deeply classified. No one who knew what had happened could go on the record. They couldn't even mention the names of the spy satellites involved. They couldn't give me confirmation or not.

I had to go looking for a proper smoking gun, proper evidence that confirmed beyond all reasonable doubt in my mind that this is what happened and this is how it happened and when it happened and where it happened. That was a fantastic and exciting piece of detective work, which I hope I've kind of brought to life in an exciting and a dramatic way in the book. [Countdown: 10 Amazing Space Shuttle Photos]

Space.com: An interesting part of the book for me is how you talk about how they designed it for the stresses and also the whole heat shield issue.

White: They couldn't use the same approach they had used in Apollo. They couldn't use an ablative shield because it was by definition not reusable because its destruction was the thing that protected it by creating a sort of layer of plasma gas. You couldn't use metal because it buckled and twisted under heat, and the gaps that it would create would destroy the airframe. And so they had to look for something entirely new, and they settled on sand, essentially, silica sand.

You know that the surface of a desert is, essentially, impervious to heat and cold. It doesn't change shape, however hot it gets or however cold it gets. And that was the quality of the silica that was so valued in the tiles. But it was also brittle, so you couldn't just attach big sheets of it to the shuttle airframe because the shuttle airframe is made of metal. You see an airliner's wings flex as you go through turbulence. The shuttle, while it may have been more rigid a structure than an airliner wing, twisted, flexed and moved through different parts of the flight envelope. And big sheets of that silica material would have cracked and crumbled as the machine underneath it twisted.

So they made this incredible mosaic of 33,000 tiles, each one individually numbered and shaped, and that was what protected the aluminum skin beneath from the temperatures on the other side of the tile of 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Aluminum melts at 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit. And so, two or three inches of silica tile — which are incredible light — are managing to prevent that incredible heat on the other side reaching the skin beneath it. It was a really novel and ingenious solution to the problem of the heat shield.

[Engineers developed a method of keeping the fragile tiles attached to the orbiter. But, they miscalculated the strength of the sonic shock wave produced by the shuttle's two solid rocket motors. The shock wave — 10 times more powerful than projected — bounced off the launch pad and knocked tiles off the back of the orbiter.]

Space.com: There were some rather harrowing aspects of the re-entry as well, right?

White: I mentioned the body flap, which was critical to controlling the shuttle, and the point at which it looked as if they might exceed the limits that the body flap could cope with and lose control of the shuttle as a result. The other thing that was not anticipated was the extent to which the shuttle's tail would kind of fishtail, would sort of swing outside of the expected limits.

And this is quite an interesting point. This is something John Young was always quick to point out. It demonstrated on that occasion just how critical the computers were to the shuttle's fortunes. What was happening with that porpoising tail was that it was beyond what a human pilot could have coped with. So without the avionics, without the computers supporting what John Young was doing, again, the limitations of what the shuttle could have coped with would have been exceeded, and she would have been lost. It was a high-wire act, that first flight. The only way of establishing whether the space shuttle system worked, whether or not that 10-year design process, the computers, the heat shield, the solid rocket motors, the main engines, the only way of working out and proving that all of that worked ultimately was to fly her. And so that's why that first shuttle flight was described by contemporaries of Young and Crippen as the boldest test flight in history. Because it was the only occasion before or since, and I'm sure it will never happen again, it's been the only occasion where a manned spacecraft has ever been launched with a crew on board without first being tested in an unmanned configuration.

Space.com: That's true. You had monkeys flying on Mercury and you had a bunch of unmanned tests in Gemini and Apollo.

White: But, here Young and Crippen ponied up and strapped themselves into the cockpit. We get used to acts of courage from astronauts, but it was an extraordinarily ballsy thing to do.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Douglas Messier is the managing editor of Parabolicarc.com, a daily online blog founded in 2007 that covers space tourism, space commercialization, human spaceflight and planetary exploration. Douglas earned a journalism degree from Rider University in New Jersey as well as a certificate in interdisciplinary space studies from the International Space University. He also earned a master's degree in science, technology and public policy from George Washington University in Washington, D.C. You can follow Douglas's latest project on Twitter and Parabolicarc.com.