Boeing Starliner's 'Last Room on Earth' for Astronauts – Photo Tour

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

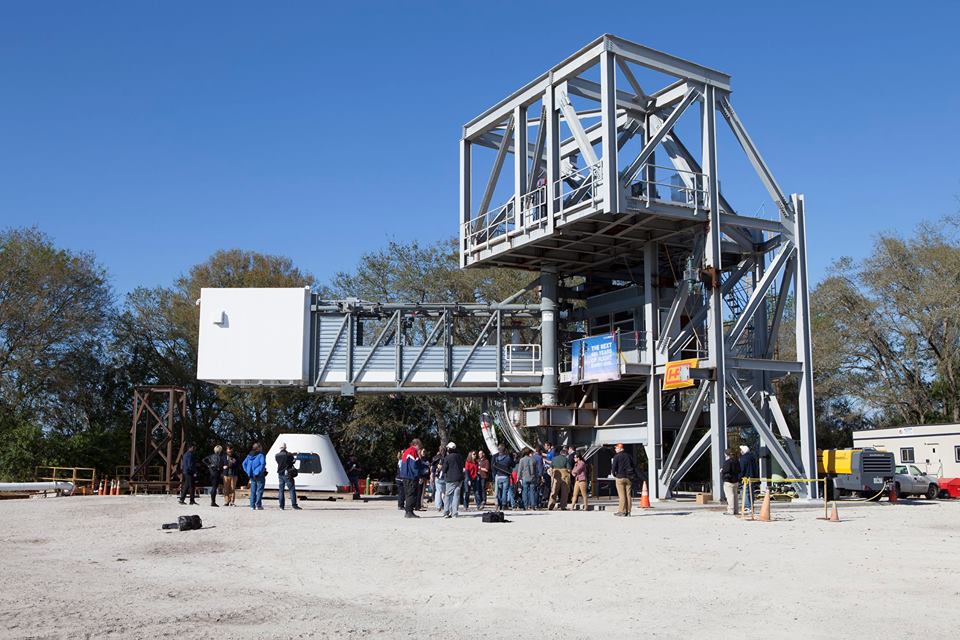

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. -- Last week, reporters got a chance to visit a service structure under construction for Boeing's CST-100 Starliner spacecraft — including the "White Room," the final place astronauts will wait before blasting off.

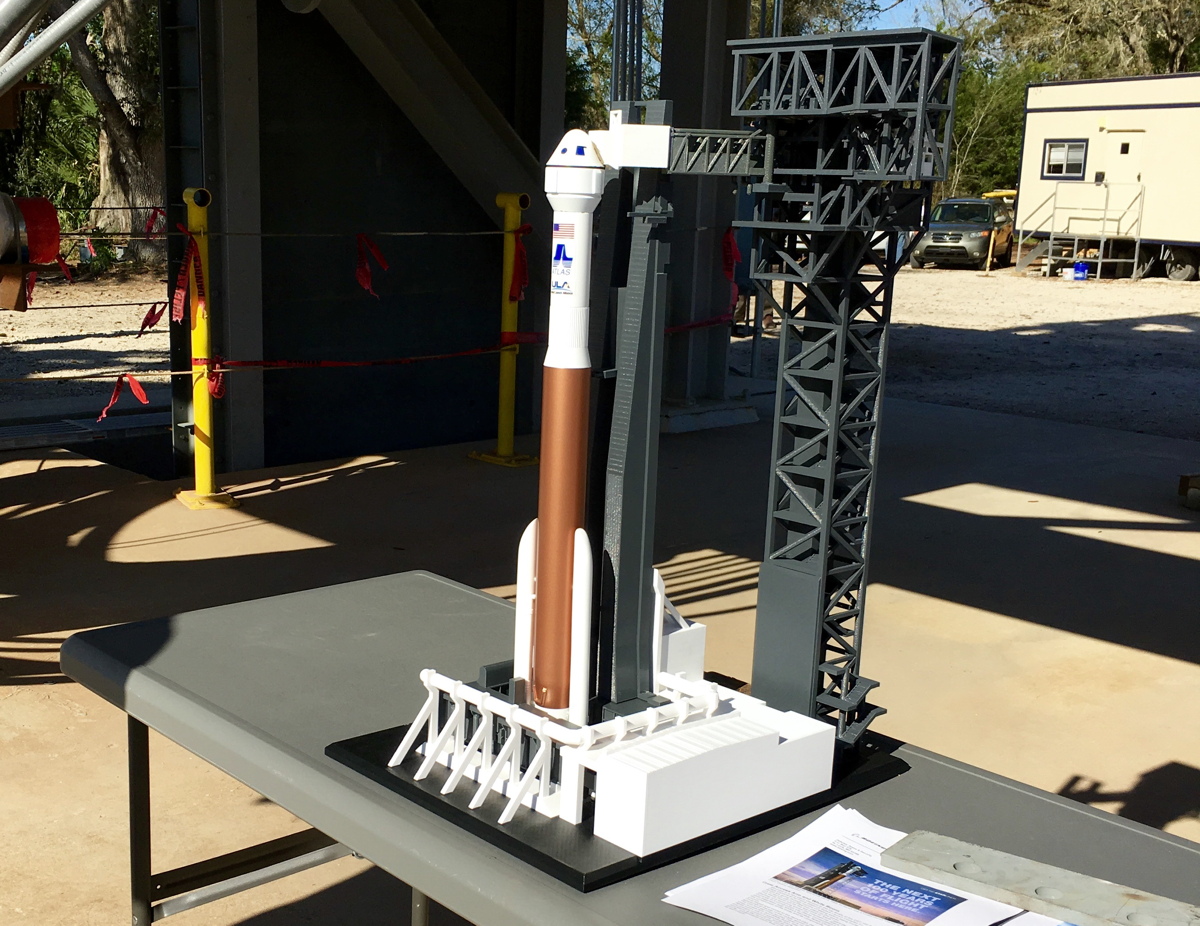

After a long ride from NASA's Kennedy Space Center here through the wildlife refuge surrounding it, our bus full of space journalists pulled up at a construction site where engineers are putting together the Starliner's Crew Access Arm, a 44-foot (13 meters) mobile arm that will touch the tip of the rocket to let astronauts board. The craft would ride on an Atlas V rocket built by United Launch Alliance (ULA). Boeing and SpaceX have both been funded by NASA to develop spacecraft to propel astronauts to the International Space Station by 2017.

Leading the equipment tour were Boeing and ULA officials and NASA liaisons, including Boeing's director of Crew and Mission Operations, Chris Ferguson — a retired NASA astronaut who piloted the first mission of the space shuttle Atlantis. [CST-100: Images of Boeing's Private Space Capsule]

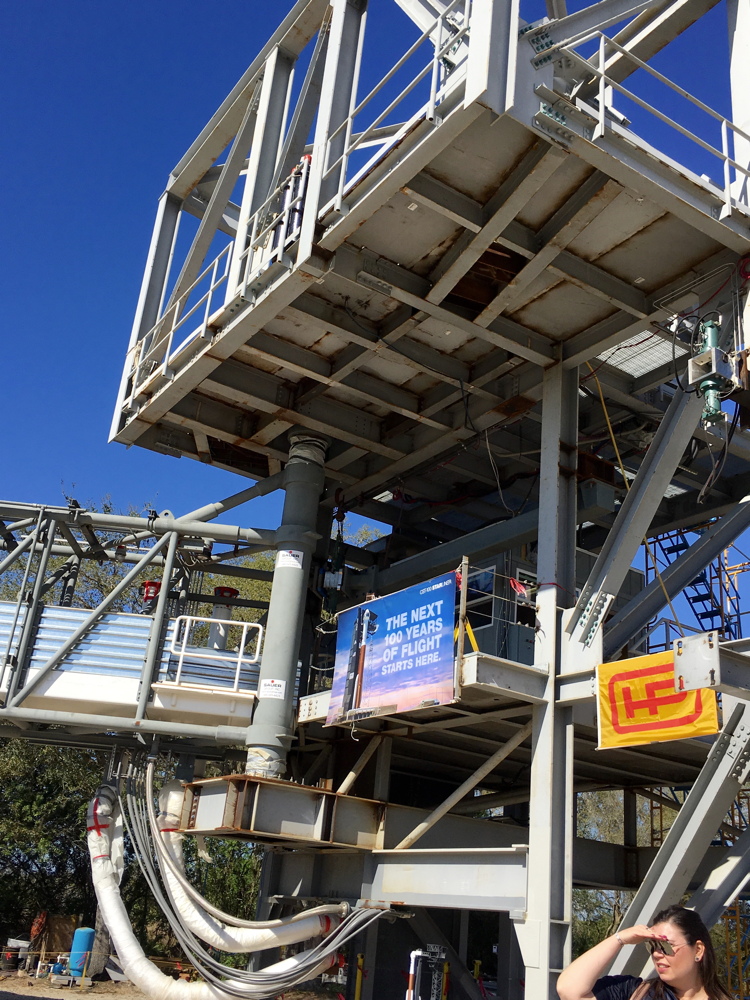

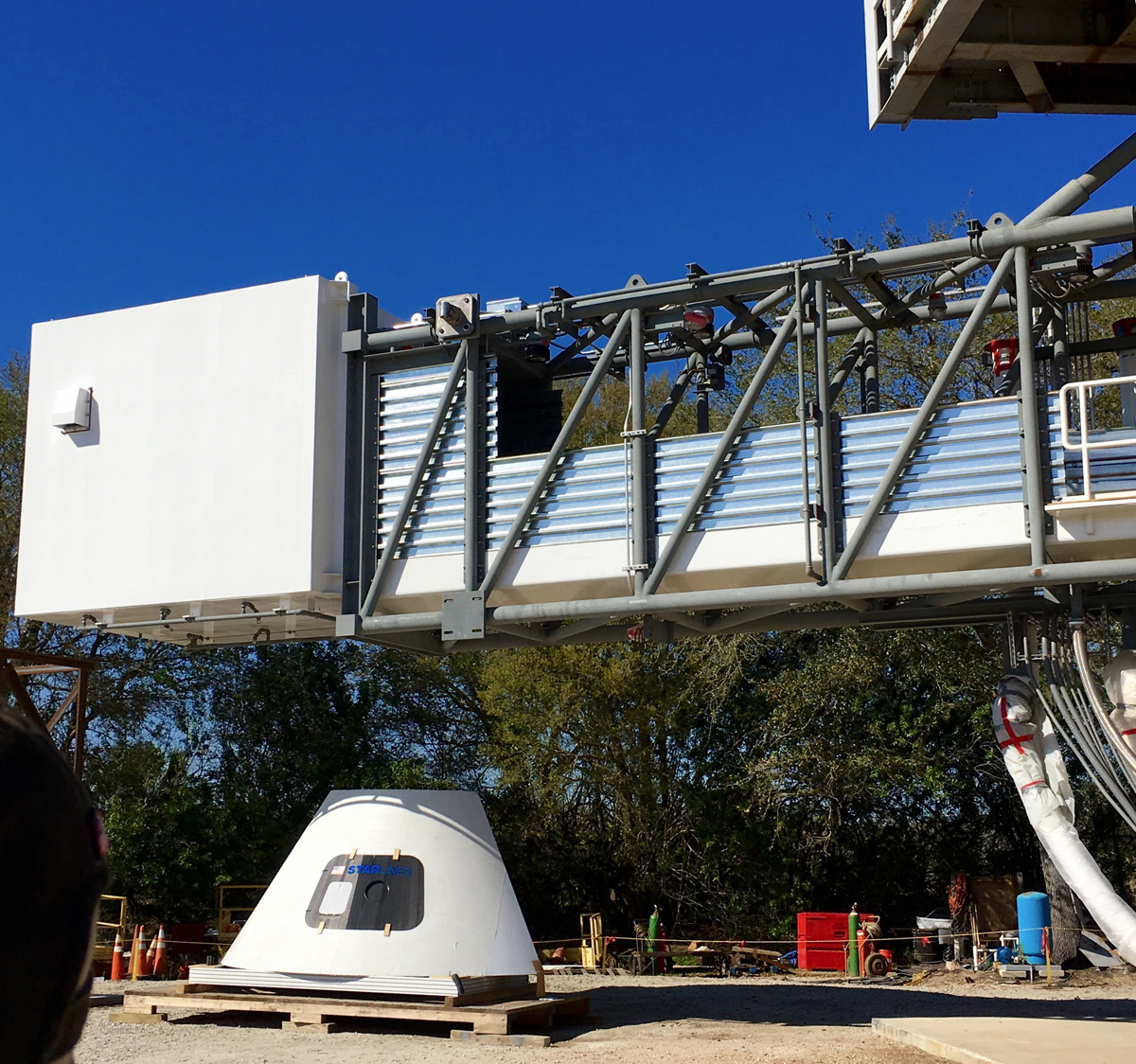

"This, behind me, is the business end of it all," Ferguson told the crowd. "It's affectionately called the 'last place on Earth' for the passengers, and brings back a lot of fond memories of Pads 39A and B," he said, referring to space shuttle launch pads. "It's a little spacier than the old one, which is really nice, got a little extra room."

The white-painted room at the end of the Crew Access Arm is a key part of the mission: It keeps the inside of the spacecraft uncontaminated as ground crew work to get the astronauts situated inside the spacecraft. About an hour before launch the astronauts will be sealed into the spacecraft, but they can be brought back out in case of a long wait or if the craft is canceled due to weather. (They can also unstrap and get out on their own, if necessary.)

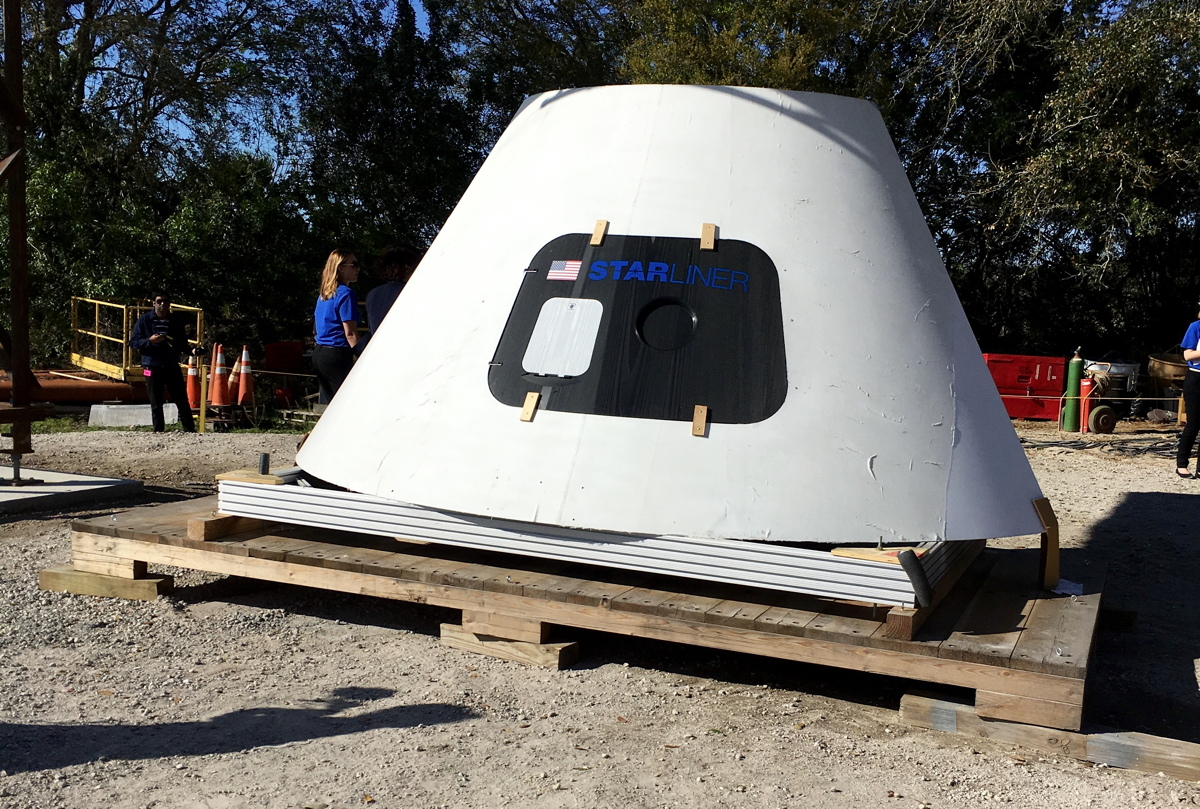

The engineers building the Crew Access Arm and White Room do not have access to an actual crew capsule, so they have a mock-up of the front half that can be mounted to work on the interface between the room and the spacecraft.

If everything went according to plan on a given launch, the Crew Access Arm would swing out to the rocket more than 200 feet (61 m) in the air, acting as a bridge for the astronauts to get to the craft. Starting about 9 minutes before launch, engineers would swing the arm 120 degrees back out of the way over the course of 2 minutes. It uses hydraulic power to make that journey, said Steve Hirsch, the arm control engineer (called an ACE, he pointed out).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But in the case of an emergency, it can snap back in just 15 seconds, using a counterweight: "We use gravity — that never fails — to get the arm out and make sure that the arm is in a position where it can get the astronauts out," Hirsch said. [Boeing's Private Space Capsule: CST-100 (Infographic)]

While the Crew Access Arm is situated close to the ground for now, it will eventually be removed from its moorings, driven down to Space Launch Complex 41 — where ULA currently stages Atlas V launches — and mounted on the full Crew Access Tower. That whole process should be complete by the end of 2016, Boeing officials said. But it'll be awhile longer before the real spacecraft makes its way over as well.

"The reason that we have this test article here, the crew hatch — and it is a full-scale model that ULA built — is because we won't have the actual spacecraft interfacing with this equipment until two weeks before our first test launch," said Lisa Locks, Boeing's launch site integration lead. "That's when it will be installed on the launch vehicle and rolled out for the first time."

Starliner will undergo an uncrewed and crewed test launch before bringing its first astronauts to the International Space Station, ideally in 2017, NASA officials said. NASA awarded Boeing two such crew missions.

"Once we do start going to ISS, that is going to enable us to add one crewmember that will allow us to double the science capabilities that are going to be able to be performed on the ISS," said Mike Ravenscroft, the NASA commercial crew program launch site integration manager working with Boeing. "It's good to see hardware starting to come to fruition […] Once that rolls out to Pad 41 and enters the Florida skyline, we're excited about that, because that will enable us to once again launch to the ISS and the journey will begin for the crew."

"If there's nothing that brings back fond memories and the palpable feeling that work is getting done, it's seeing hardware show up on the horizon," Ferguson said.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.