A global contest to name 32 alien planets has entered the home stretch.

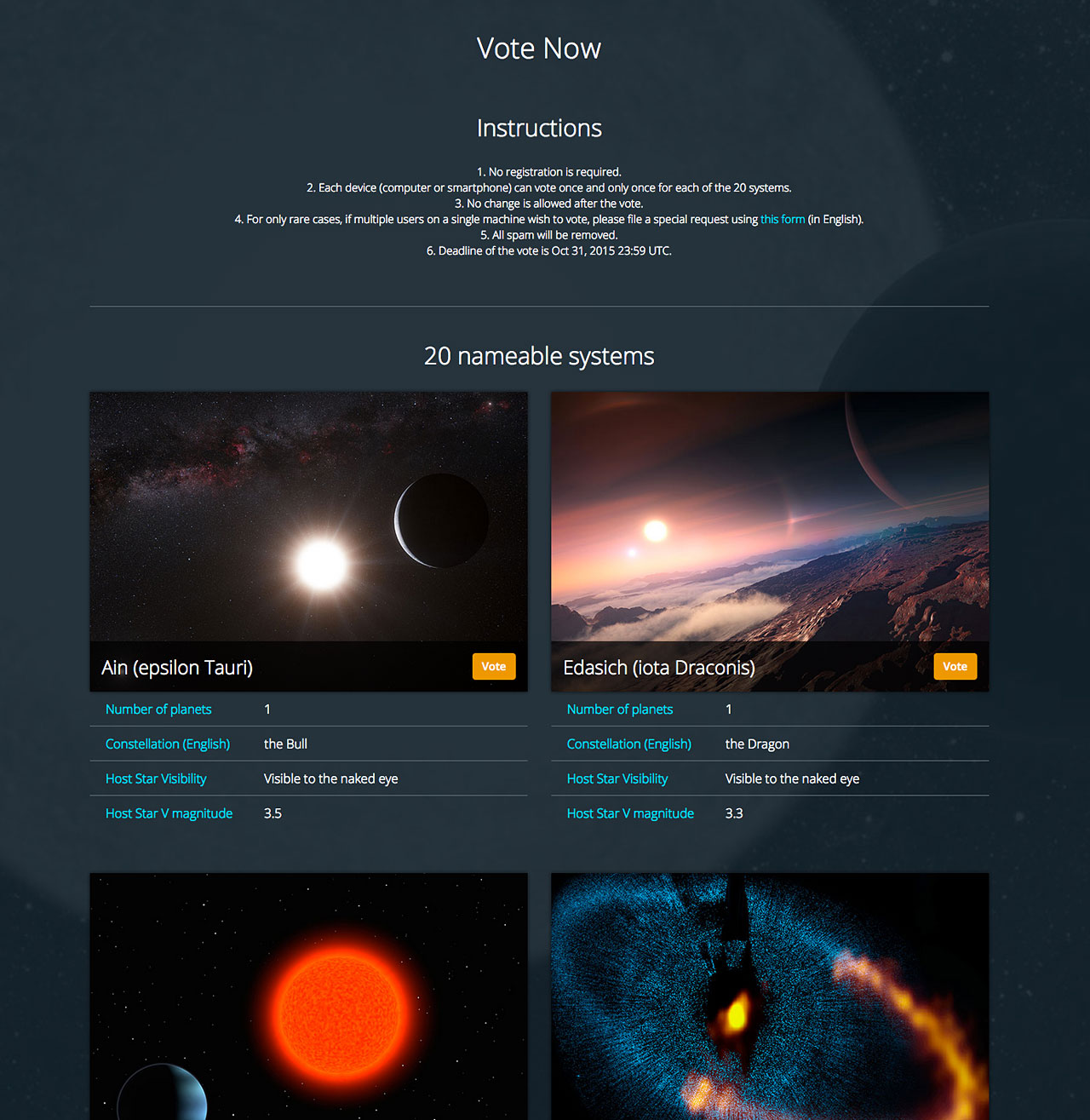

The public can now vote on a list of proposed common names for the 32 exoplanets, as well as most of their host stars, in the International Astronomical Union's "NameExoWorlds" competition. Voting is open through Oct. 31, and the winning names will be announced in mid-November, IAU representatives said.

NameExoWorlds kicked off in July 2014, when the IAU — which assigns "official" names to celestial objects and their surface features — chose an initial group of 260 extrasolar systems containing 305 well-characterized alien worlds. (Astronomers have discovered nearly 2,000 exoplanets to date.) [The Strangest Alien Planets]

In January 2015, astronomy clubs and nonprofit organizations around the world began voting to determine which 20 of these 260 systems would be open to public naming. The 20 that were selected harbor 32 known alien planets, some of them quite famous. For example, one of them is 51 Pegasi b, which in 1995 became the first alien planet ever discovered around a sunlike star.

In April, the clubs and nonprofits started submitting proposals to name these alien worlds and 15 of the host stars. (The other five stars already have common names and were therefore off-limits.) A total of 247 proposals were received from groups in 45 different countries, IAU representatives said.

And now it's the broader public's turn to participate in NameExoWorlds. Public voting on the proposed names officially opened Tuesday evening (Aug. 11) during a ceremonly at the IAU's 29th General Assembly in Honolulu, with astronomer Lisa Kaltenegger from Cornell University casting the first vote.

To vote, go to the NameExoWorlds site here: http://nameexoworlds.iau.org/exoworldsvote

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Voting is free and requires no registration. Each computer, smartphone or tablet will be permitted to cast just one vote for each of the 20 exoplanetary systems, IAU representatives said.

And a single click will take care of a system's star and planet(s), for the proposals link them together; there is no mixing and matching. For example, in the case of the 51 Pegasi system, the choices for voters are: 51 Pegasi (star) and Epicurus (planet); pegasusfeather and soryolen; Umisachi and Yamasachi; Jiguang and Matafeiyan; Apollonis and Neil; Carousel and Carousel Hell b; Starry Bunnies and Tortoise; Chrysaor and Hydrogen; Helvetios and Dimidium; Carl and Dot; or Mondufemom and Prantriguse. (The reasoning behind each proposed name is given at the voting site.)

NameExoWorlds isn't the first project that invites the public to name exoplanets. The company Uwingu has launched several such efforts over the past few years, charging small amounts to propose and vote on appellations for alien worlds. (Uwingu's stated chief goal is helping fund space research, exploration and education efforts.)

While one of these projects was going on, the IAU issued a press release asserting its status as the sole authority in the exoplanet-naming process and stressing that it's not possible to buy an "official" name. While Uwingu wasn't mentioned by name, the press release seemed to be a response to the company's activities.

Uwingu representatives, for their part, said they had always made clear that their projects dealt with "people's choice" exoplanet names, not officially recognized ones.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.