How to Spot Asteroid Pallas in Binoculars and Telescopes This Week

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Most of us have played video games shooting at asteroids, or watched a starship maneuvering through the asteroid belt on television. But have you ever seen a real asteroid in the sky? This week is an excellent opportunity to see one of the largest asteroids, Pallas, as it reaches opposition to the sun.

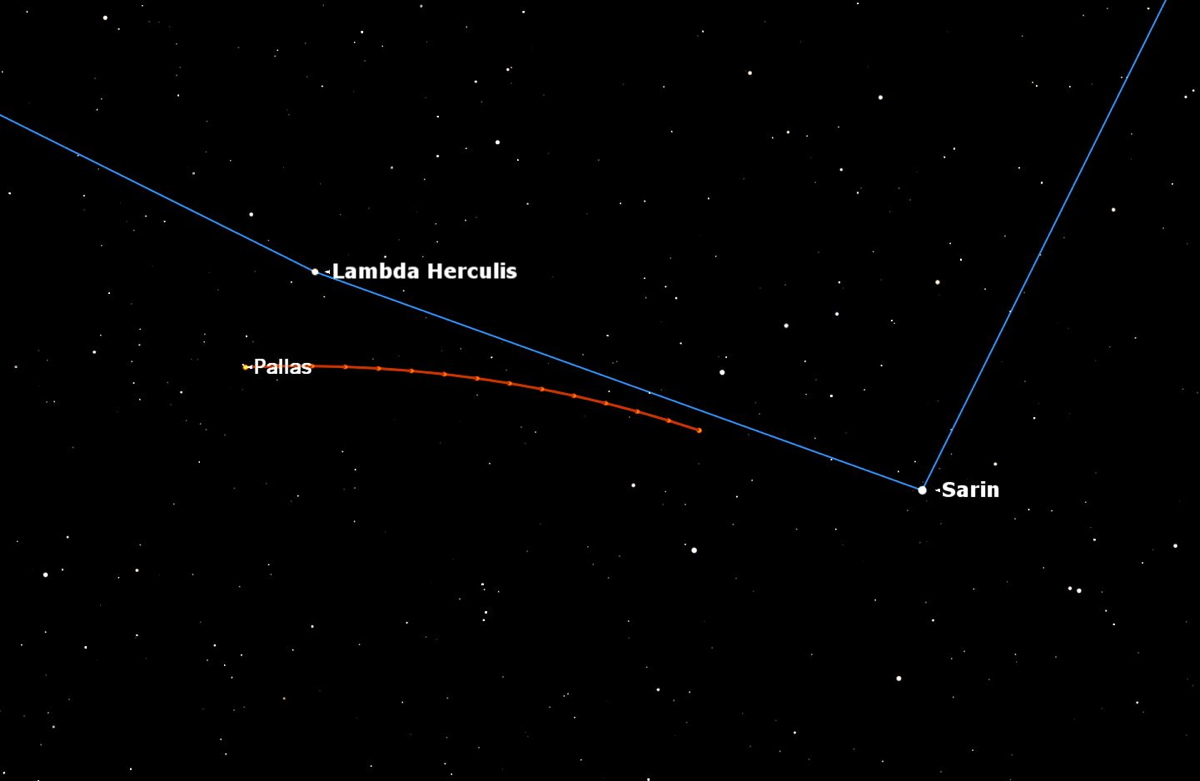

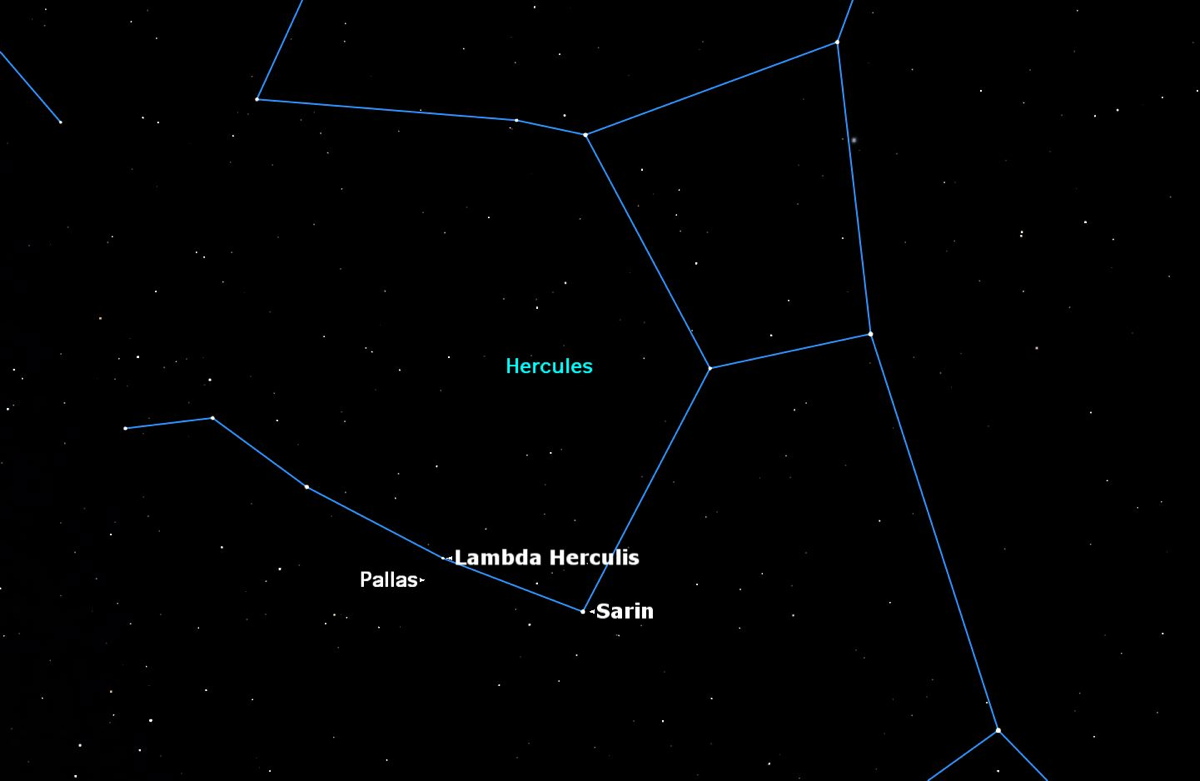

This week, the asteroid Pallas reaches opposition in the eastern part of Hercules, very close to the 4th magnitude star Lambda Herculis. It is motoring along from east to west at about one degree per week, so that in three weeks time it will be close to the 3rd magnitude star Sarin (Delta Herculis). Its movement from night to night, as seen in binoculars, is quite obvious.

At opposition, Pallas will reach magnitude 9.4, making it easily visible in binoculars. It will be 2.405 astronomical units from Earth, or 224 million miles (360 million kilometers). One astronomical unit is the average distance between the Earth and the sun, about 93 million miles (150 million km). [Astronomy Gear Guide for Stargazers]

The first asteroids were discovered in the early years of the 19th century, with the first four asteroids, including Pallas, discovered in a six-year between 1801 and 1807. A fifth asteroid was not discovered until 38 years later in 1845. This ushered in a rich period of asteroid discovery, with three dozen more discoveries in the next decade. Once photography came into play, thousands more asteroids were found.

Astronomers originally thought the first asteroids were very small planets, but once they realized how numerous they were, they created a special category called "asteroids" (because of their resemblance to stars) or "minor planets." The vast majority of these asteroids have orbits between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, a region of the solar system that came to be known as the "asteroid belt."

In reality, the asteroid belt is quite different from what you see in science fiction programs. Rather than being crowded with space rocks, the asteroid belt is mostly empty space. Most of the time, if you were standing on one asteroid, you would need binoculars or a telescope to spot the nearest asteroid. The chances of two asteroids colliding is virtually zero.

The first asteroid discovered, Ceres, has now been reclassified as a dwarf planet, along with Pluto and Eris. At 592 miles (952 kilometres) in diameter, it is significantly larger than the remaining asteroids. Two asteroids, Pallas and Vesta, are almost identical in size, 326 miles (524 km) and 318 miles (512 km) respectively. The rest range from Hygiea (276 miles/444 km) on down through chunks of rock only 30 feet (10 meters) across. Anything smaller than that is called a "meteoroid."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Although Pallas and Vesta are nearly identical in size, they are quite different in their composition and appearance. Pallas is a typical rocky asteroid, quite dark in surface colour, resembling a carbonaceous chondrite meteorite. Vesta, on the other hand, is highly reflective, the only asteroid sometimes visible with the naked eye.

For the rest, binoculars are needed to spot them. Asteroids, as their name implies, look exactly like faint stars. What gives them away is their rather rapid movement against the background stars.

I particularly like watching asteroids when they are passing close to a bright star. In a telescope, you can see their movement over even a 15-minute period.

Editor's note: If you capture an amazing view of the night sky that you'd like to share with Space.com, send photos and comments in to: spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.