'The Science of 'Interstellar' (US 2014): Book Excerpt

Famed physicist Kip Thorne brought real science to this year's sci-fi movie epic "Interstellar."

In his new book "The Science of 'Interstellar'" (W.W. Norton & Company, 2014), Thorne goes into detail about the physics that underlies the awesome phenomena explored in the movie, including black holes, time dilation, a disease that could decimate food crops on Earth and an alien planet with 4,000-foot-tall (1,200 meters) water waves.

Thorne is a theoretical physicist at the California Institute of Technology who has a history of probing the limits of what's possible in our universe. This is Thorne's second book. His first, "Black Holes and Time Warps: Einstein's Outrageous Legacy" (W.W. Norton & Company, 1995), is one of the premier popular physics books on black holes. [Related: 'Interstellar' Science: Physcist Kip Thorne Writes the Book]

In the following excerpt from "The Science of Interstellar," Thorne discusses the reality of "Miller's planet" — a planet that orbits dangerously close to the black hole known in the film as Gargantua. Because of the black hole's strong gravity, Miller's planet experiences extreme time dilation: time moves significantly more slowly on the surface of the planet than on Earth (or even on the main spaceship, parked a safe distance away). In this excerpt from Chapter Six of Thorne's book, he explains the circumstances that would make Miller's planet a reality:

Gargantua's Mass

Miller’s planet (which I talk about at length in Chapter 17) is about as close to Gargantua as it can possibly be and still survive. We know this because the crew’s extreme loss of time can only occur very near Gargantua.

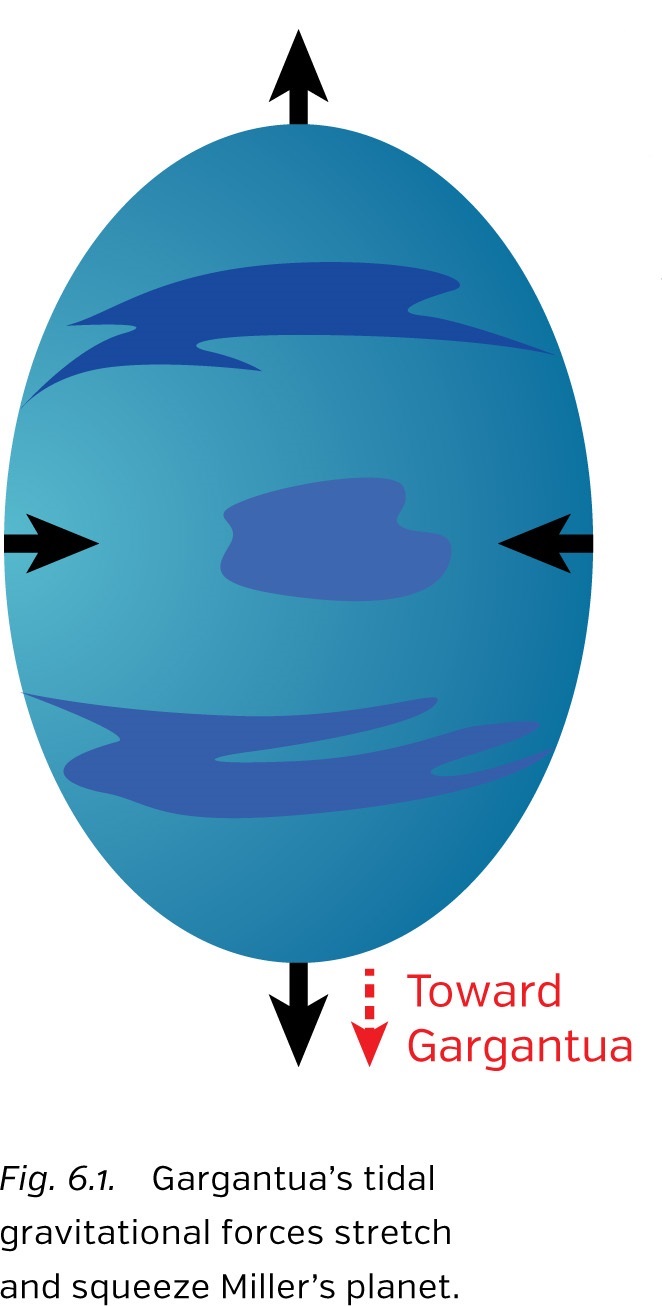

At so close a distance, Gargantua’s tidal gravitational forces (Chapter 4) are especially strong. They stretch Miller’s planet toward and away from Gargantua and squeeze the planet’s sides (Figure 6.1). The strength of this stretch and squeeze is inversely proportional to the square of Gargantua’s mass. Why? The greater Gargantua’s mass, the greater its circumference, and therefore the more similar Gargantua’s gravitational forces are on the various parts of the planet, which results in weaker tidal forces. (See Newton’s viewpoint on tidal forces; Figure 4.8.) Working through the details, I conclude that Gargantua’s mass must be at least 100 million times bigger than the Sun’s mass. If Gargantua were less massive than that, it would tear Miller’s planet apart!

In all my science interpretations of what happens in Interstellar, I assume that this actually is Gargantua’s mass: 100 million Suns.3 For example, I assume this mass in Chapter 17, when explaining how Gargantua’s tidal forces could produce the giant water waves that inundate the Ranger on Miller’s planet.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The circumference of a black hole’s event horizon is proportional to the hole’s mass. For Gargantua’s 100 million solar masses, the horizon circumference works out to be approximately the same as the Earth’s orbit around the Sun: about 1 billion kilometers. That’s big! After consulting with me, that’s the circumference assumed by Paul Franklin’s visual-effects team, when producing the images in "Interstellar."

Physicists attribute to a black hole a radius equal to its horizon’s circumference divided by 2π (about 6.28). Because of the extreme warping of space inside the black hole, this is not the hole’s true radius. Not the true distance from the horizon to the hole’s center, as measured in our universe. But it is the event horizon’s radius (half its diameter) as measured in the bulk; see Figure 6.3 below. Gargantua’s radius, in this sense, is about 150 million kilometers, the same as the radius of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun. [Black Hole Quiz: How Well Do You Know Nature's Weirdest Creations?]

FOOTNOTES: 3: A more reasonable value might be 200 million times the Sun’s mass, but I want to keep the numbers simple and there’s a lot of slop in this one, so I chose 100 million.

Gargantua's Spin

When Christopher Nolan told me how much slowing of time he wanted on Miller’s planet, one hour there is seven years back on Earth, I was shocked. I didn’t think that possible and I told Chris so. “It’s non-negotiable,” Chris insisted. So, not for the first time and also not the last, I went home, thought about it, did some calculations with Einstein’s relativistic equations, and found a way.

I discovered that, if Miller’s planet is about as near Gargantua as it can get without falling in4 and if Gargantua is spinning fast enough, then Chris’s one-hour-in-seven-years time slowing is possible. But Gargantua has to spin awfully fast.

There is a maximum spin rate that any black hole can have. If it spins faster than that maximum, its horizon disappears, leaving the singularity inside it wide open for all the universe to see; that is, making it naked—which is probably forbidden by the laws of physics (Chapter 26).

I found that Chris’s huge slowing of time requires Gargantua to spin almost as fast as the maximum: less than the maximum by about one part in 100 trillion.5 In most of my science interpretations of "Interstellar," I assume this spin.

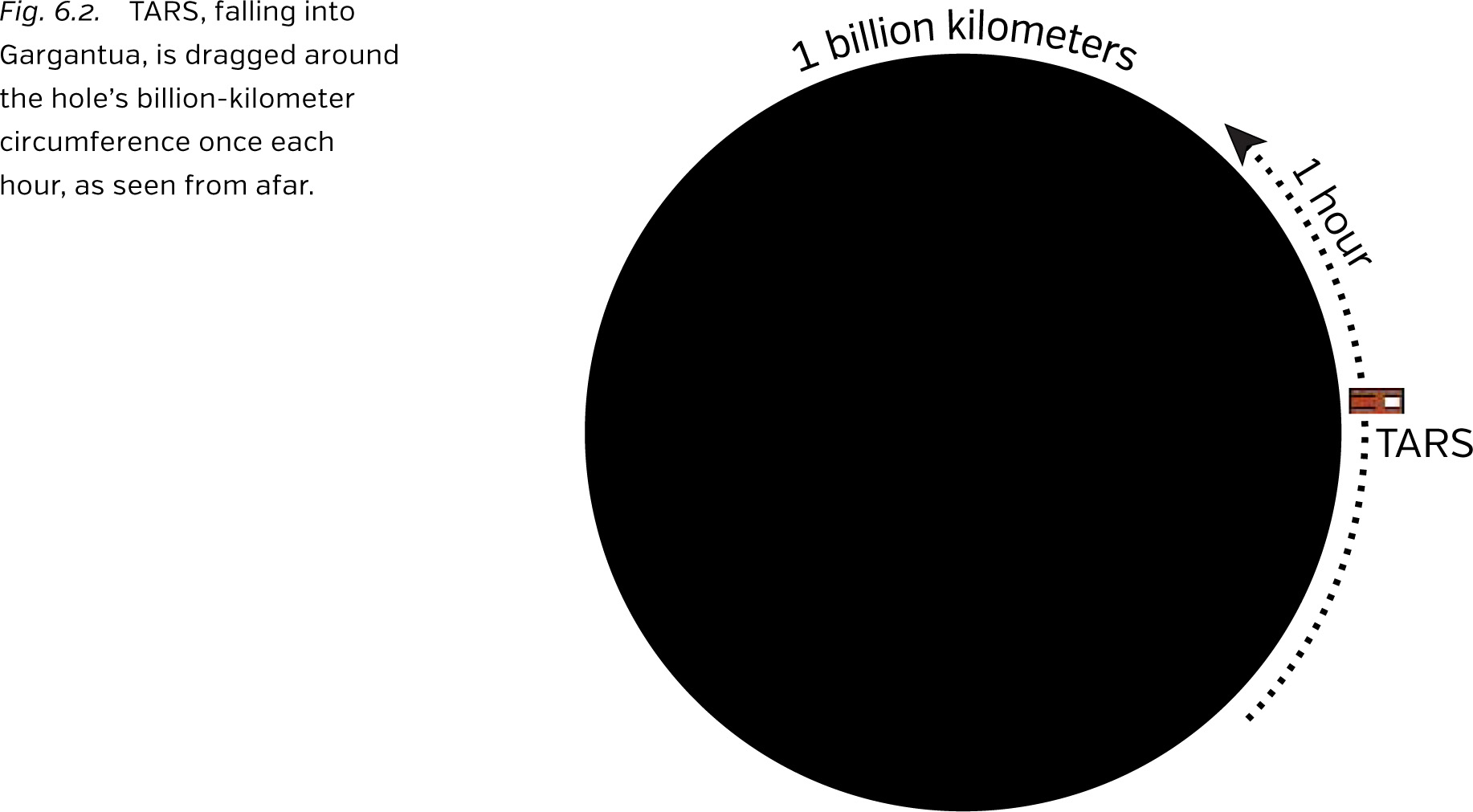

The crew of the Endurance could measure the spin rate directly by watching from far, far away as the robot TARS falls into Gargantua (Figure 6.2).6 As seen from afar, TARS never crosses the horizon (because signals he sends after crossing can’t get out of the black hole). Instead, TARS’ infall appears to slow down, and he appears to hover just above the horizon. And as he hovers, Gargantua’s whirling space sweeps him around and around Gargantua, as seen from afar. With Garantua’s spin very near the maximum possible, TARS’ orbital period is about one hour, as seen from afar.

You can do the math yourself: the orbital distance around Gargantua is a billion kilometers and TARS covers that distance in one hour, about a billion kilometers per hour, which is approximately the speed of light! If Gargantua were spinning faster than the maximum, TARS would whip around faster than the speed of light, which violates Einsteinʼs speed limit. This is a heuristic way to understand why there is a maximum possible spin for any black hole.

In 1975, I discovered a mechanism by which Nature protects black holes from spinning faster than the maximum: When it gets close to the maximum spin, a black hole has difficulty capturing objects that orbit in the same direction as the hole rotates and that therefore, when captured, increase the hole’s spin. But the hole easily captures things that orbit opposite to its spin and that, when captured, slow the hole’s spin. Therefore, the spin is easily slowed, when it gets close to the maximum.

In my discovery, I focused on a disk of gas, somewhat like Saturn’s rings, that orbits in the same direction as the hole’s spin: an accretion disk (Chapter 9). Friction in the disk makes the gas gradually spiral into the black hole, spinning it up. Friction also heats the gas, making it radiate photons. The whirl of space around the hole grabs those photons that travel in the same direction as the hole spins and flings them away, so they can’t get into the hole. By contrast, the whirl grabs photons that are trying to travel opposite to the spin and sucks them into the hole, where they slow the spin. Ultimately, when the hole’s spin reaches 0.998 of the maximum, an equilibrium is reached, with spin-down by the captured photons precisely counteracting spin-up by the accreting gas. This equilibrium appears to be somewhat robust. In most astrophysical environments I expect black holes to spin no faster than about 0.998 of the maximum.

However, I can imagine situations—very rare or never in the real universe, but possible nevertheless—where the spin gets much closer to the maximum, even as close as Chris requires to produce the slowing of time on Miller’s planet, a spin one part in 100 trillion less than the maximum spin. Unlikely, but possible.

This is common in movies. To make a great film, a superb filmmaker often pushes things to the extreme. In science fantasy films such as "Harry Potter," that extreme is far beyond the bounds of the scientifically possible. In science fiction, it’s generally kept in the realm of the possible. That’s the main distinction between science fantasy and science fiction.

Interstellar" is science fiction, not fantasy. Gargantua’s ultrafast spin is scientifically possible.

Footnotes:

4: See Figure 17.2 and the discussion of it in Chapter 17.

5: In other words, its spin is the maximum minus 0.00000000000001 of the maximum.

6: When TARS falls in, the Endurance is not far, far away, but rather is on the critical orbit, quite near the horizon, whirling around the hole nearly as fast as TARS; so Amelia Brand, in the Endurance, does not see TARS swept around at high speed. For more on this, see Chapter 27.

Excerpted from The Science of Interstellar by Kip Thorne. Copyright © 2014 by Kip Thorne. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

BUY "The Science of 'Interstellar'" >>

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter