A guide to the Canadian Space Agency: Key missions, achievements, and future plans

Discover everything you need to know about the Canadian Space Agency, including its missions, achievements, and role in space exploration.

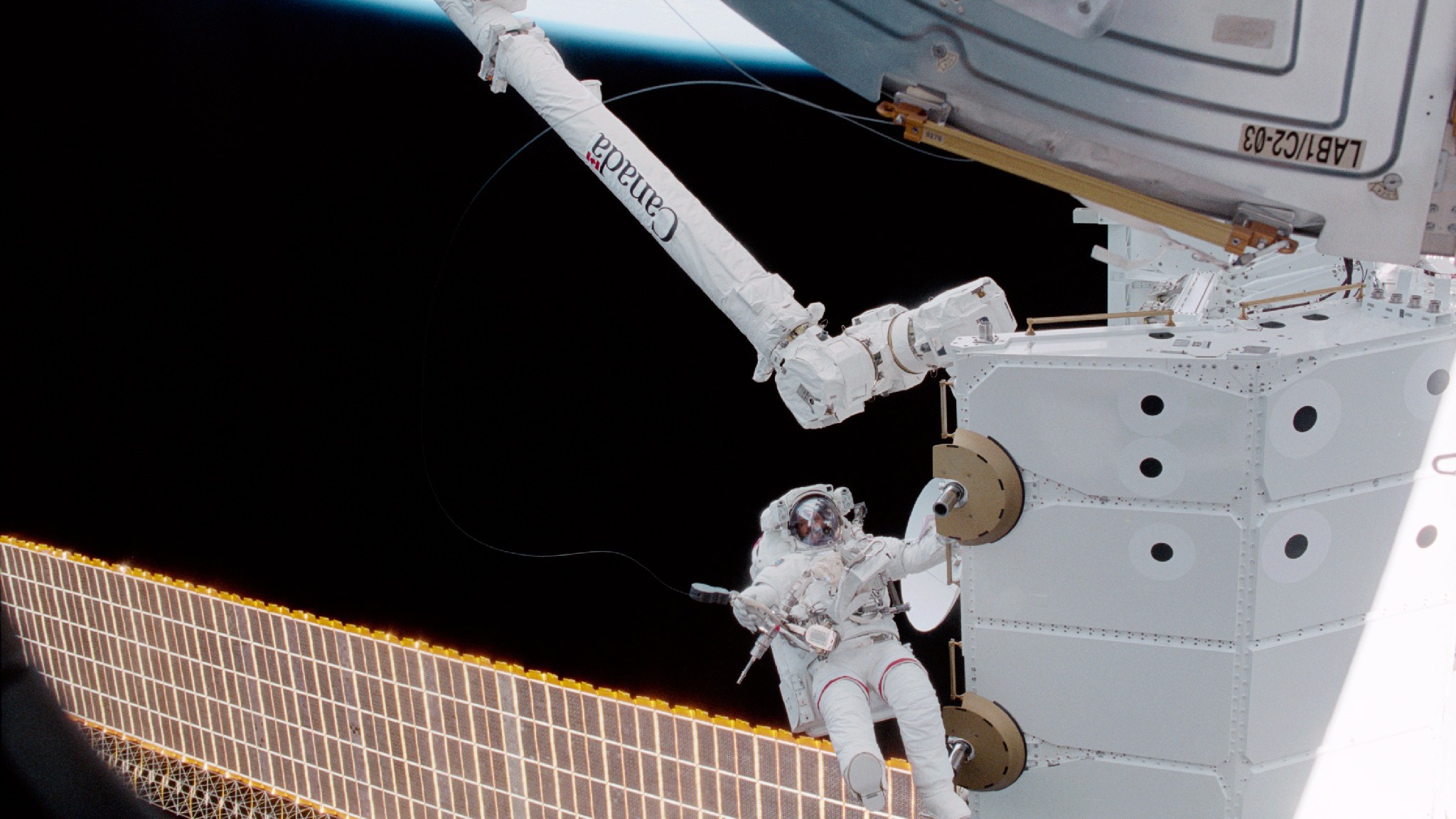

The Canadian Space Agency (CSA), established in 1989, is a civilian government space agency that aims to promote the peaceful use of space for the benefit of Canadians. Its most high-profile projects include the Canadarm robotic arm series and the Artemis 2 moon mission, which will feature CSA astronaut Jeremy Hansen.

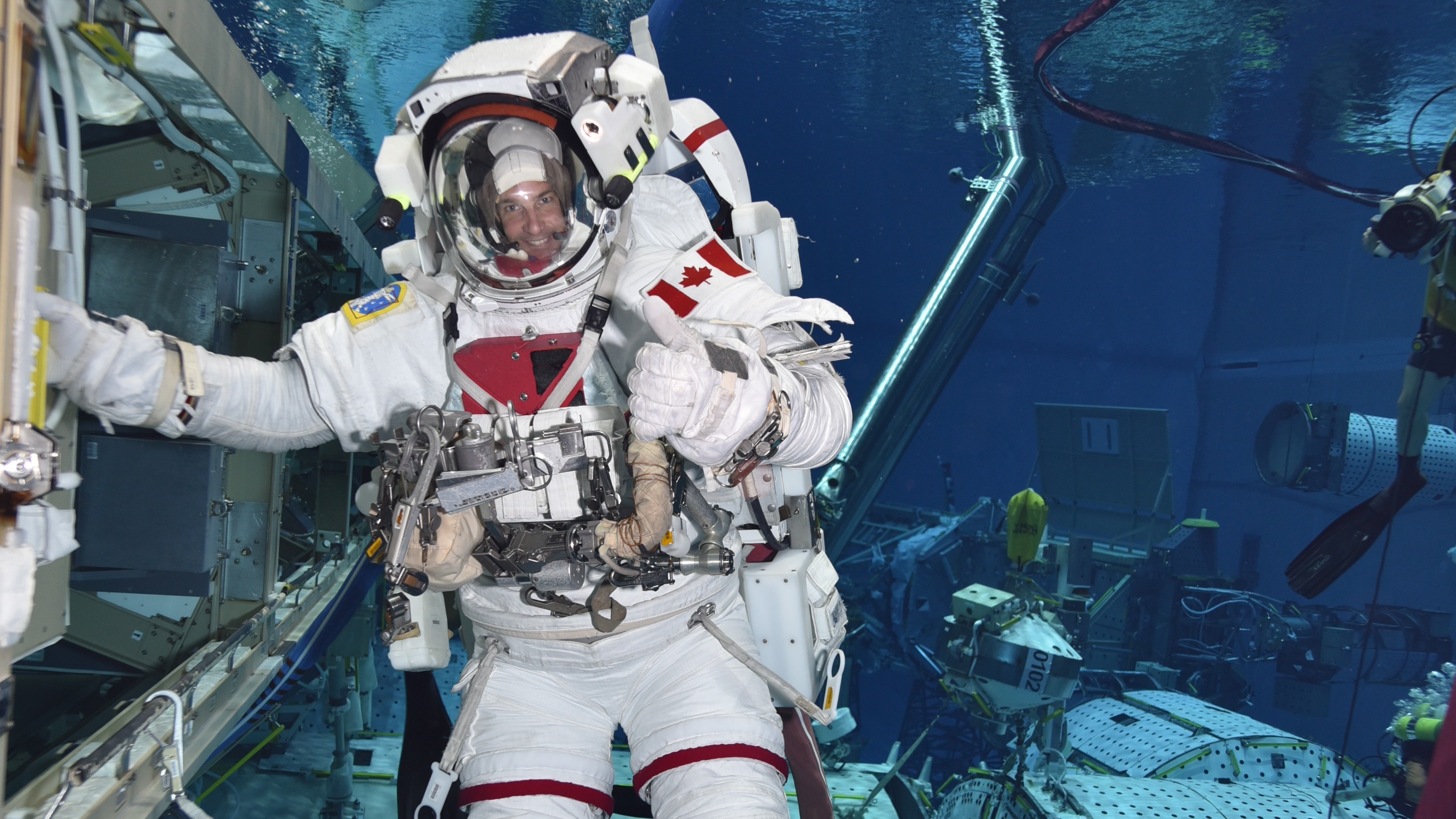

The Canadian astronaut program predates the CSA. The agency and its predecessors have recruited 14 astronauts across four campaigns. Most of those individuals flew in space. The most famous of these astronauts was Chris Hadfield, who commanded the International Space Station (ISS) in 2013 after having flown on two previous missions.

Traditionally, compared with NASA (which usually has an annual budget of something like $27 billion, depending on the year), the CSA has received a smaller annual budget of roughly CA$400 million ($300 million USD). The CSA thus relies heavily on collaboration. NASA has been the CSA's longtime launching partner, through seats and science secured with the Canadarm series. The CSA also partners with other government departments and with Canadian companies to supply satellites and technology, with an eye toward commercialization where possible.

Canadian governments have been criticized by entities like the Canadian Global Affairs Institute for leaving long gaps between the space strategy updates that determine the amount of funding the CSA receives. That said, the 2023 federal budget for the CSA included substantial new funds on top of the agency's annual budget: CA$2.5 billion ($1.84 billion) for science related to the Gateway space station, a planned lunar outpost led by NASA; extending ISS participation to 2030; and a lunar utility vehicle; among other things. That money will be spread over as many as 14 years, depending on the program. Another major tranche of funding in 2019 was issued for the development of Canadarm3, a new robotic arm.

Related: Artemis 2's Canadian astronaut got their moon mission seat with 'potato salad'

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022. Her reporting includes multiple exclusives with the Canadian Space Agency and talking with Canadian astronauts on the International Space Station.

CSA Frequently asked questions

Does CSA work with NASA?

Yes, CSA works with NASA. CSA is a member of the International Space Station consortium, among many other projects.

What is the Canadian Space Agency known for?

The CSA is known for several astronauts, such as Chris Hadfield and Jeremy Hansen. It also is known for providing the Canadarm series of robotic arms.

Who are the four active Canadian astronauts?

The four active CSA astronauts are Jenni Gibbons, Jeremy Hansen, Joshua Kutryk and David Saint-Jacques. Canadians may also fly to space with NASA or a private company, however.

Canadian space before the CSA

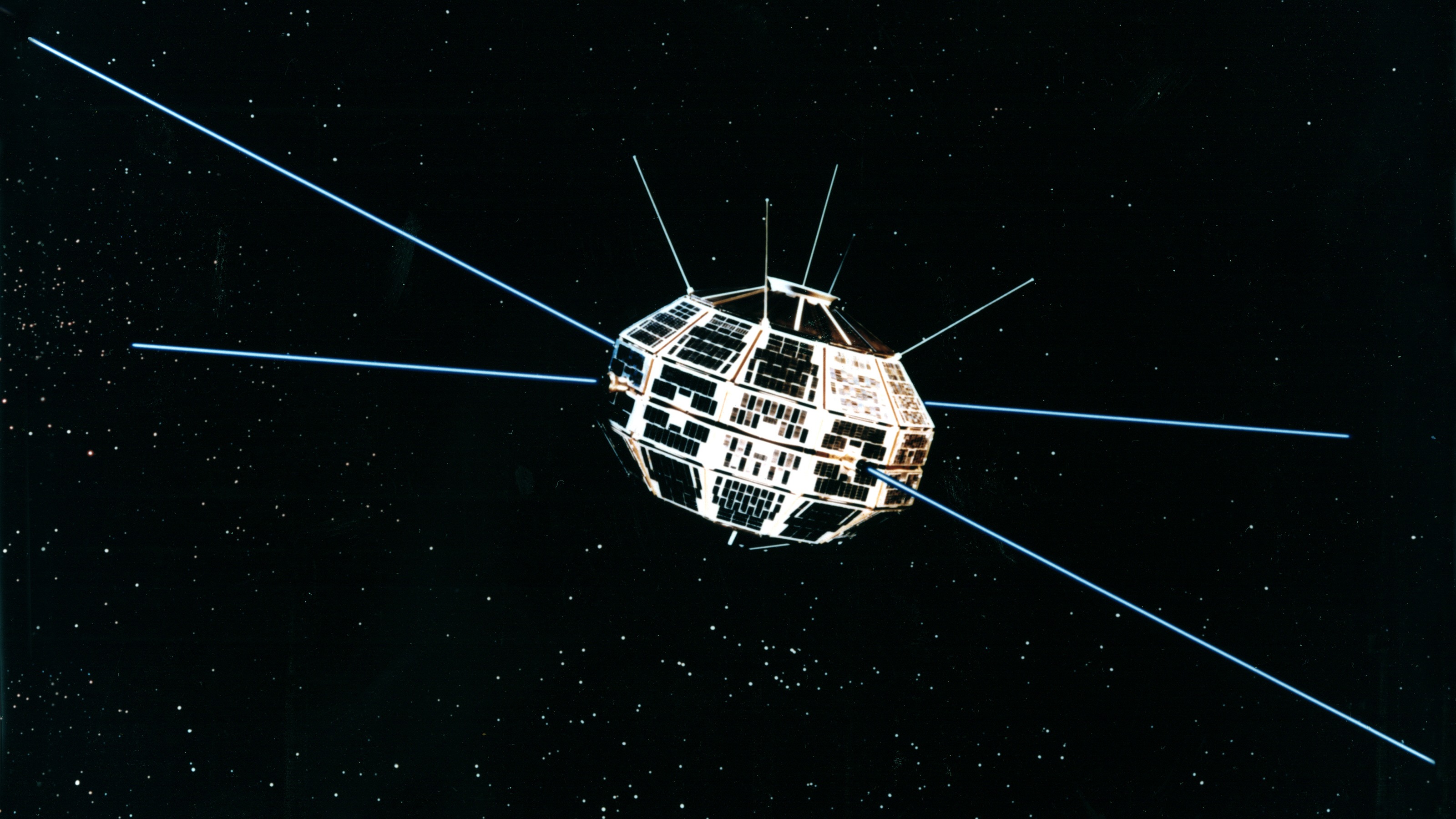

Government-funded civilian space activities predate the formation of the CSA by decades, through activities such as radio communications and sounding rockets that probed the upper atmosphere. The first Canadian satellite, Alouette, was built under the purview of a now-defunct Canadian government department known as the Defence and Research Telecommunications Establishment (DRTE), according to the CSA's materials. Alouette went into space in 1962 atop a U.S. rocket.

Modern-day CSA activities can be traced to the 1967 Chapman Report, also known as "Upper Atmosphere and Space Programs in Canada." John Herbert Chapman, chairman of the report committee, was a DRTE physicist and space scientist who played a key role in Alouette. The report was immensely influential in government policy, according to The Canadian Encyclopedia, as the country shifted its satellite activities from science to commercial applications.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Other offshoots of the report include Canada's Anik A1 communication satellite in 1972 and the communications company Telesat, originally formed as a Crown (government-owned) corporation, in 1969.

Related: Best mobile apps to identify space stations and satellites

Chapman also recommended that Canada create its own space agency rather than sharing responsibilities among other departments. Other government champions, such as then-Science Minister Jeanne Sauvé in 1974, voiced their support over the decades. But the formation of the CSA would not come for another 22 years after the Chapman Report.

Early Canadarm work

Canadarm also predates the CSA's establishment by decades. In fact, the story begins on a 1951 sea voyage from Liverpool, England. George Klein, an inventor with Canada's National Research Council (NRC), examined cigarette paper he was rolling and, from that, had an idea to create a collapsible tube system for space use, according to Space.com staff writer Elizabeth Howell's book "Canadarm and Collaboration (ECW Press, 2020). The information originally came from Richard I. Bourgeois-Doyle's 2004 NRC book, "George J. Klein: The Great Inventor."

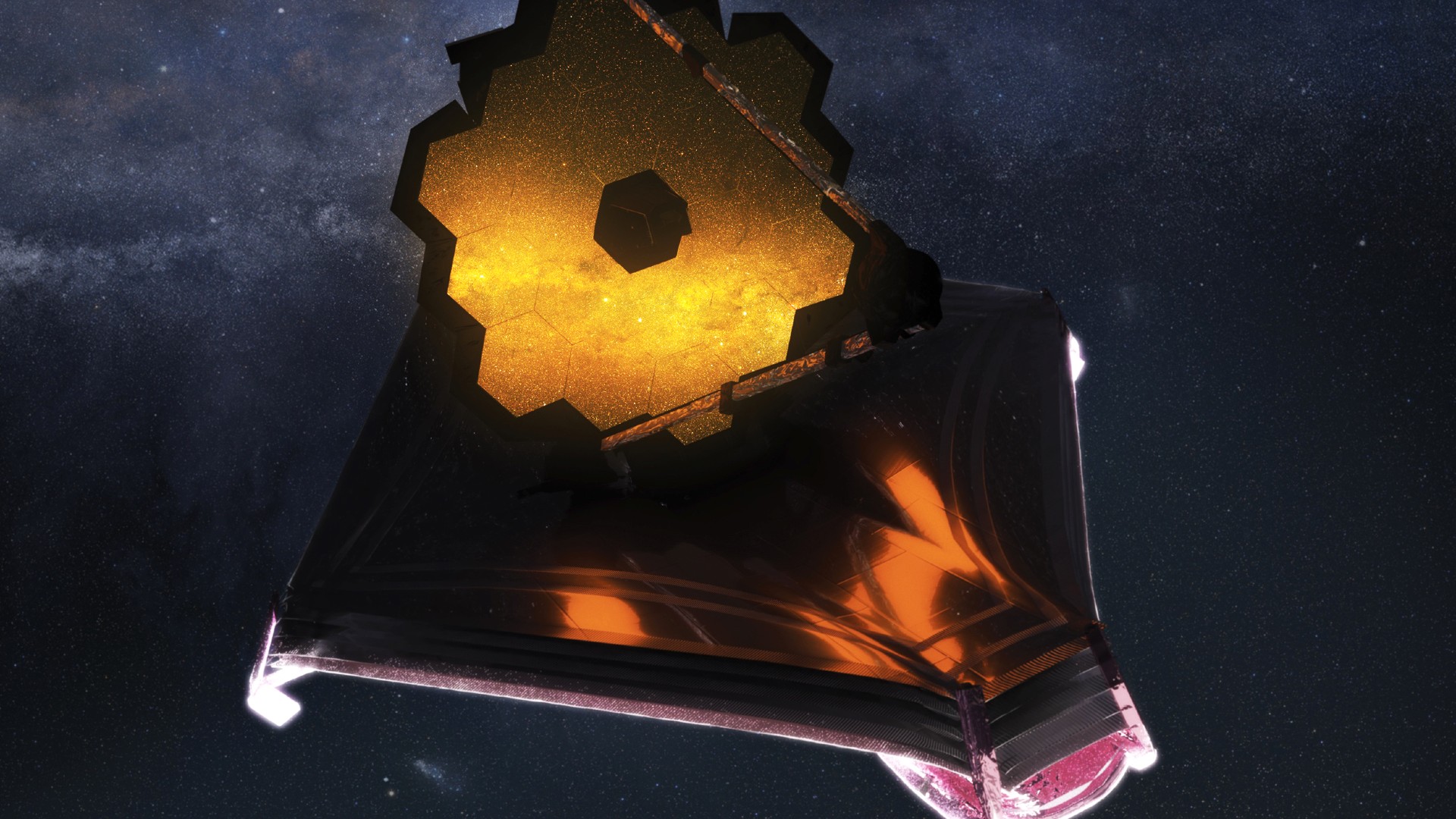

Klein's work led to an antenna type called the Storable Extendible Tubular Member, which can roll up for launch and then unfurl in space. The technology first flew on Alouette and continues venturing to space regularly, including on the James Webb Space Telescope in 2021.

As Canada was flying satellites and its STEM antenna in space, NASA was deciding on the next directions for its human space programs after the Apollo moon missions of the 1960s and 1970s and the Skylab space station. The history of the space shuttle and the ISS are lengthy, but very simply put, NASA decided to pursue multinational collaborations in the 1970s as part of its space policy. One reason was to reduce costs, and another was to create allies and deepen friendships across multiple policy objectives. Canada was included in those discussions with NASA.

Related: 'An entirely new way of thinking': The ISS celebrates 20 years in space

In 1974, NASA and Canada's NRC signed an agreement that, in essence, promised Canadian science missions on the space shuttle in exchange for a robotic arm (later called Canadarm), according to "Canadarm and Collaboration." Notably, the agreement did not discuss astronauts.

Canadarm flew on numerous space shuttle missions, starting with STS-2 in November 1981, and exceeded NASA's expectations. (Today, the Canadarm series is managed by Canadian company MDA Space with CSA funding, but back in those days, the project was led by Spar Aerospace and funded by Canada's NRC.)

Canadian astronauts

Around the late 1970s, NASA created a new class of astronaut, known as a "payload specialist," who could, in some cases, be a foreign national responsible for a small set of experiments. This opened the door for a Canadian astronaut program. In 1979, NASA extended an invitation for Canadian astronauts to Chapman personally, but the invitation somehow got lost when Chapman, 58, died suddenly, according to Howell's book and an April 2, 1981 article from "The Ottawa Citizen."

Then, in 1983, NASA's Enterprise test space shuttle was making a "goodwill" tour of international stops, including in Canada. During the shuttle's visit to Ottawa in June (which Howell, by good fortune, attended as an infant with her parents), then-NASA Administrator Jim Beggs promised his agency would invite Canada to send Canadian experiments, along with a Canadian astronaut, into space.

That effort launched a recruitment campaign in 1983 that brought in six new Canadian astronauts, including luminaries like Marc Garneau (who, in 1984, became the first Canadian astronaut in space) and Roberta Bondar (who, in 1992, became the first Canadian woman in space). Their seats were paid for by Canadarm, which, in its lifetime, serviced the Hubble Space Telescope and assisted on shuttle spacewalks. After the Columbia space shuttle disaster of 2003, Canadarm (including a long extender) was repurposed to scan the bottom of each shuttle with a camera to look for any loose heat shield tiles, which was one of the causes of Columbia's demise.

Related: 20 years after Columbia shuttle tragedy, NASA pledges 'acute awareness' of astronaut safety

The success of Canadarm brought on successors. Canadarm2 was launched in 2001 for the ISS and was co-installed by Hadfield, who also received a rendition of Canada's anthem in space from NASA mission control. A handy robot helper, Dextre, followed in 2008. Canadarm2 was also repurposed in 2012 to assist certain cargo spacecraft in berthing to the ISS — a use for which it was not originally envisioned.

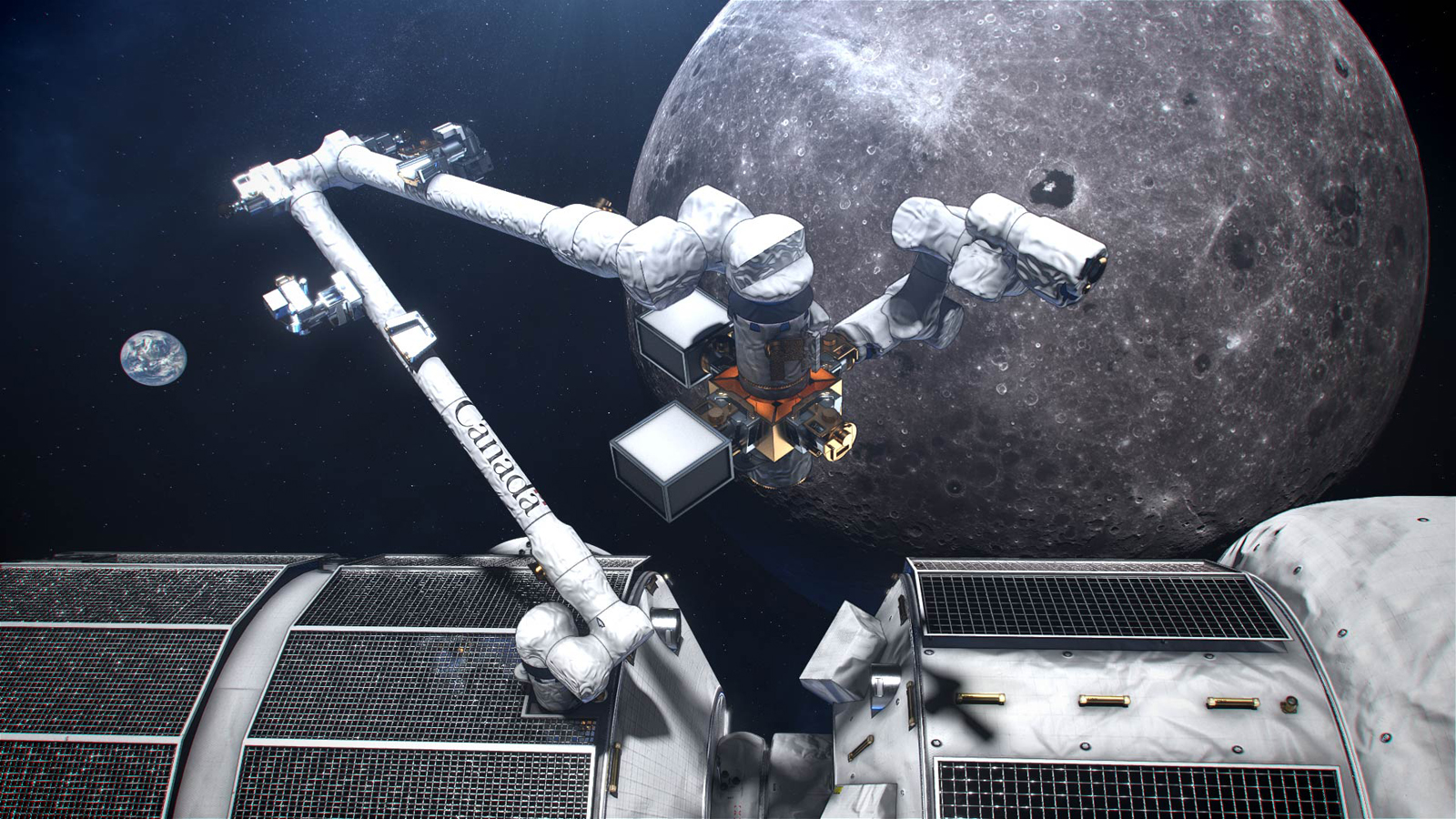

The next generation of the robotic arm, Canadarm3, is expected to serve NASA's Gateway space station, which will orbit the moon. Gateway will support Artemis program missions to the lunar surface. Canada's contribution, which includes artificial intelligence for Canadarm3, funded the seat aboard Artemis 2. At least one other Gateway mission is guaranteed for the CSA.

Related: What it's like to snag a spacecraft with the International Space Station's robotic arm

Notable Canadian astronaut missions

Canadians have flown in space privately and for NASA, but this section focuses on the Canadian government's astronauts. At first, the government program was managed by Canada's NRC. Then, after the CSA was formed in 1989, government astronauts flew on behalf of the CSA.

The first Canadian astronauts were payload specialists, meaning they were responsible for certain experiments on the shuttle and did not perform duties such as spacewalks. Garneau, Bondar and Steve MacLean — who flew in 1984, 1992 and 1992, respectively — were all payload specialists.

As the program and the ISS planning matured, NASA invited certain Canadians to train as mission specialists to help the country gain more experience for space station missions. Canada also issued a second recruitment of astronauts that brought four new people on board in 1992. Subsequently, Garneau and Hadfield, a new trainee at the time, were the first certified mission specialists. (NASA later extended shuttle mission specialist training to more astronauts, and then to all astronauts by default.)

Related: Life in space: Astronaut Chris Hadfield's video guide

Major CSA milestones in the 1990s and 2000s included the first Canadian woman in space (Bondar, in 1992), the first Canadian on the Russian space station Mir (Hadfield, in 1995), the first Canadian to operate the Canadarm (Hadfield, in 1995), the first Canadian to visit the ISS (Julie Payette, in 1999) and the first Canadian to do a spacewalk (Hadfield, in 2001.)

An astronaut recruitment in 2008-2009 brought on two new astronauts: Hansen and David Saint-Jacques. In 2013, Hadfield became the first Canadian commander of the ISS. Saint-Jacques had his first flight in 2018-2019, and Hansen is expected to fly his moon mission in 2025 or so. (The slow pace of flight assignments is in part due to the CSA's relatively small share of ISS funding, at 2.3%, since flights are based upon partner contributions.)

CSA currently has four astronauts, although Canadians can and do fly to space by other means. Hansen is assigned to Artemis 2, and Saint-Jacques is not assigned to a new mission for the moment. The two others, Joshua Kutryk and Jenni Gibbons, were selected in 2017. Kutryk will fly on the Boeing Starliner-1 mission in 2025 or so for a six-month mission to the ISS, and Gibbons is backup to Hansen.

Other CSA activities

Robotics and astronauts take the lion's share of CSA attention, but the agency is also involved in other types of space work.

The David Florida Laboratory in Ottawa is a test bed for satellites before they reach space. Satellites there are shaken, baked and put through electronic interference tests to make sure they are ready for launch. CSA may close the laboratory in 2025, but is exploring other uses for the space.

The agency also has funded a suite of Earth observation satellites that monitor the planet's surface for natural disasters, changes in agriculture and even ship activities. The most famous set is the Radarsat series; Radarsat-1 launched in 1995, Radarsat-2 in 2007 and the Radarsat Constellation (a trio of satellites) in 2019. Successor Radarsat satellites are also in the works.

Payloads from CSA-funded projects have also traveled to other locations. For example, the Mars Curiosity rover's Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (funded by the CSA) has been analyzing the composition of rocks on the Red Planet for more than 10 years. A Canadian laser flew to asteroid Bennu aboard NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission. Several Canadian experiments are on the ISS, focusing on aspects such as aging on Earth and the effects of weightlessness. Artemis 2 experiments have not yet been announced.

Closer to Earth, the AuroraMAX camera provides live views of auroras in the skies over Yellowknife, in Canada's Northwest Territories. In Earth orbit, the SciSat satellite examines the ozone layer and its depletion, particularly over northern Canada. Aboard NASA's Terra satellite, the Measurements of Pollution in the Troposphere instrument examines atmospheric pollutants in Earth's atmosphere. The CSA also offers cubesat opportunities periodically for Canadian students.

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, which launched in 2021, includes participation from the CSA. Canada provided the fine guidance sensor for the telescope to point in space, as well as a near-infrared imager and spectrograph.

CSA expert Q&A

François-Philippe Champagne is the Canadian government minister (a federal politician with a portfolio of duties) responsible for the CSA. He reports directly to Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Champagne was first elected in 2015 and was first appointed to Cabinet in 2019; Cabinet is the group of government ministers in Canada that are each responsible for a portfolio. Champagne's portfolios have included minister of foreign affairs, minister of infrastructure and communities, and minister of international trade.

Where do you see the CSA's role in government?

The CSA brings [many] portfolios together. There's the aspect of the space economy, or aspects that will benefit communities in the Arctic with health and nutrition in harsh environments. CSA [also] brings in the foreign affairs portfolio.

In what ways do you think the CSA will benefit Canadians?

Space exploration is all about science, technology and innovation. And as a reminder, the science of today is the economy of tomorrow. You don't need to go very far to see the dividends that space is bringing; just think about GPS, which is now something commonly used by everyone.

What kinds of consultations are being done with Canadian companies?

There's a new Canadian space council [of companies] … and we do want to make sure we integrate Canadian companies in the strategic supply chain. I've been talking to a number of [international] space companies, like SpaceX, Blue Origin — and obviously talking to NASA.

This exclusive Space.com interview was done on April 2, 2023, the day before the Artemis 2 crew was announced. It has been edited and condensed.

Additional resources

Keep up with CSA activities in real time by following the agency on Twitter and Instagram, and stay up to date on news by visiting the CSA website.

Bibliography

Bourgeois-Doyle, R. I. (2004.) George J. Klein: The great inventor. National Research Council of Canada: NRC Research Press. https://www.amazon.com/George-J-Klein-Great-Inventor/dp/0660193221/

Canadian Global Affairs Institute. (2022, June.) Revitalizing Canada’s visions for space. https://www.cgai.ca/revitalizing_canadas_visions_for_space

Canadian Space Agency. (2018, September 28). Alouette I and II. https://www.asc-csa.gc.ca/eng/satellites/alouette.asp

Canadian Space Agency. (2023, March 29). Significant investments to further propel Canadian space exploration. https://www.asc-csa.gc.ca/eng/news/articles/2023/2023-03-29-significant-investments-to-further-propel-canadian-space-exploration.asp

Chapman, J. H., Forsyth, P. A., Lapp P. A., & Patterson, G. N. (1967). Upper atmosphere and space programs in Canada. Government of Canada. https://www.uottawa.ca/research-innovation/sites/g/files/bhrskd326/files/2022-08/special-study-no.-1-upper-atmosphere-and-space-programs-in-canada.pdf

Franklin, C. A. (2015, March 4). John Herbert Chapman. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-herbert-chapman

Howell, E. (2020). Canadarm and Collaboration: How Canada's astronauts and space robots explore new worlds. ECW Press. https://www.amazon.com/Canadarm-Collaboration-Canadas-Astronauts-Explore-ebook/dp/B089VGLY1Y

Kirton, J. (1990, February). Canadian space policy. Space Policy, 6(1), 61-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/0265-9646(90)90008-L

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.