Voyager Spacecraft: Beyond the Solar System

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

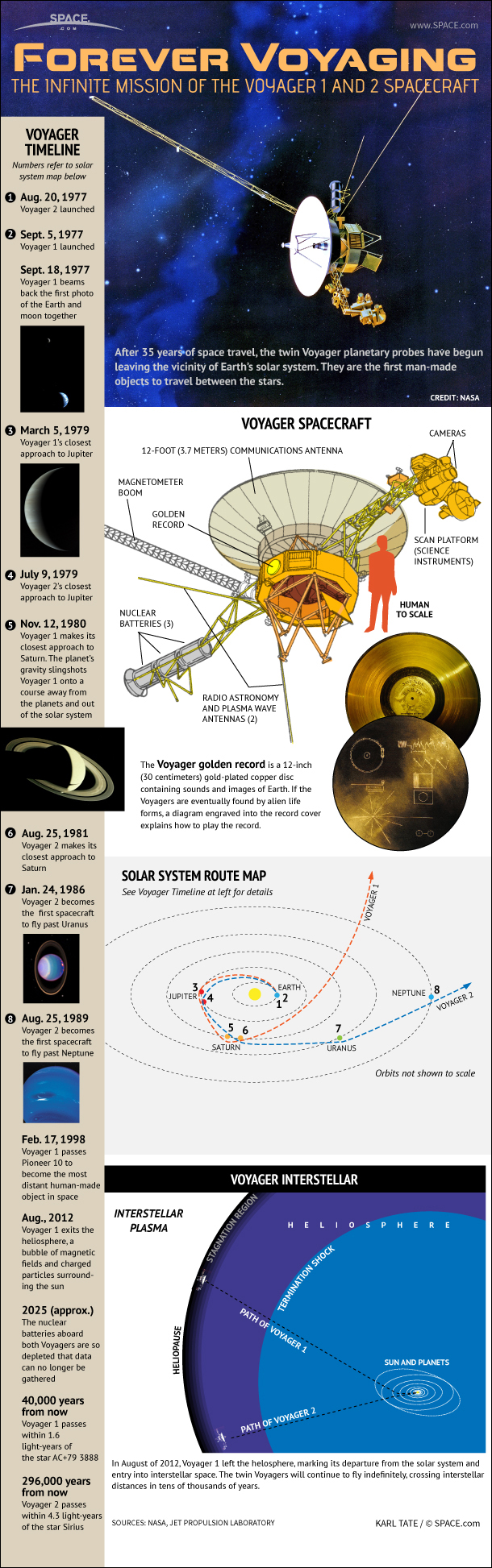

NASA's twin Voyager probes – Voyager 1 and Voyager 2- were launched in 1977 to explore the outer planets in our solar system. Voyager 2 launched on Aug. 20, 1977, and Voyager 1 launched about two weeks later, on Sept. 5. Since then, the spacecraft have been traveling along different flight paths and at different speeds. Voyager 1 passed the boundary of interstellar space in 2012, while Voyager 2 is in the outer reaches of the solar system.

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., continues to operate both spacecraft. Both are still sending scientific information about their surroundings through NASA's Deep Space Network, which is a set of antennas designed to collect data from deep-space spacecraft. In 2017, both spacecraft passed a milestone – 40 years operating in space.

NASA's longest mission

NASA launched the Voyager spacecraft in 1977 to take advantage of a rare alignment among the outer four planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune) that would not take place for another 175 years. A spacecraft visiting each planet could use a gravitational assist to fly on to the next one, saving on fuel. The original plan called for launching two spacecraft pairs — one pair to visit Jupiter, Saturn and Pluto, and the other to look at Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune. The plan was cut back due to budgetary reasons, resulting in two spacecraft: Voyager 1 and Voyager 2.

The primary five-year mission of the Voyagers included the close-up exploration of Jupiter and Saturn, Saturn's rings and the larger moons of the two planets. The mission was extended after a succession of discoveries. After passing by Saturn in 1980, Voyager 1 made a sharp turn out of the plane of the solar system. Voyager 2's trajectory, however, was planned to take it past Uranus and Neptune. While the initial budget for Voyager 2 didn't guarantee it would last long enough to transmit pictures from those two planets, it thrived and made successful flybys of Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989.

Between them, the two spacecraft have explored all the giant outer planets of our solar system — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — as well as 49 moons, and the systems of rings and magnetic fields those planets possess. [Image Gallery: Photos from NASA's Voyager 1 and 2 Probes]

On Aug. 13, 2011, Voyager 2 became NASA's longest-operating mission when it broke the previous record of 12,758 days of operation set by the Pioneer 6 probe, which launched on Dec. 16, 1965, and sent its last signal home on Dec. 8, 2000.

These are some of the Voyager program's achievements while the spacecraft were still flying past the planets, according to NASA:

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

- Examined Jupiter's atmosphere, including its hurricanes.

- Found active volcanoes on Io, a moon of Jupiter, as well as a "torus" (a ring of sulfur and oxygen that Io is shedding).

- Saw evidence of an ocean beneath Europa, an icy moon of Jupiter.

- Looked in detail at Saturn's rings; observed waves, structure and "shepherd moons" that influence the shape of its F-ring.

- Saw evidence of an atmosphere around Titan, a moon of Saturn, which scientists correctly identified as being composed largely of methane.

- Discovered a Great Dark Spot on Neptune, which is a large storm.

- Saw active geysers on Triton, an icy moon of Neptune

The current mission, the Voyager Interstellar Mission, was planned to explore the outermost edge of our solar system and eventually leave our sun's sphere of influence to enter interstellar space — the space between the stars. Since passing the boundary of interstellar space in 2012, Voyager 1 is examining the intensity of cosmic radiation, and also looking at how the sun's charged particles are interacting with particles from other stars, according to Voyager project scientist Ed Stone. Voyager 2 is still traveling within the solar system, but is expected to breach interstellar space in the next few years.

Voyager program's legacy

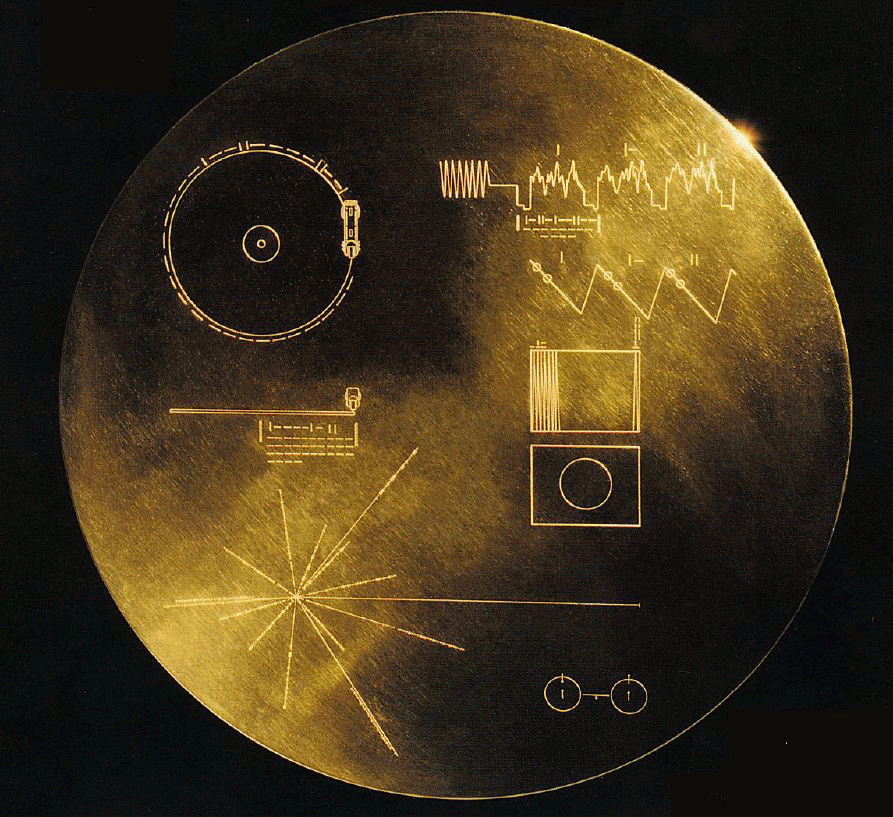

Both Voyager spacecraft carry recorded messages from Earth on golden phonograph records — 12-inch, gold-plated copper disks. A committee chaired by the late astronomer Carl Sagan selected the contents of the records for NASA.

The "Golden Records," as these records are called, are cultural time capsules that the Voyagers bear with them to other star systems. They contain images and natural sounds, spoken greetings in 55 languages and musical selections from different cultures and eras.

The program's observations of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune also provide valuable touchstones for current observations of these planets. NASA sent follow-on probes to Jupiter (Galileo, 1989-2003) and Saturn (Cassini, 1997-2017) to examine these giant planets up close for several years, following the quick glimpses provided by Voyager. Galileo and Cassini each gathered data about the icy moons at their respective planets, as well as information about the structure and composition of the giant planets themselves, among other activities.

NASA's Juno mission is currently in orbit around Jupiter, while both NASA and the European Space Agency are planning missions to examine its icy moons. The European mission is called JUICE, or JUpiter ICy moons Explorer; it is expected to launch in 2022 for arrival in 2029. NASA is planning a Europa mission that would launch no earlier than 2022, although it could depart later than that. Voyager 2 remains the only spacecraft to visit Uranus and Neptune, but astronomers followed up on its observations using telescopes — especially the Keck telescope and the Hubble Space Telescope. The resolution of these telescopes is enough to watch storms develop and dissipate on these giant planets, as well as to look at large-scale changes in the atmosphere. As of mid-2017, NASA is also contemplating developing solar system probes that would eventually fly past Uranus and Neptune.

As of February 2018, Voyager is roughly 141 astronomical units (sun-Earth distances) from Earth. That's roughly 13.2 billion miles, or 21.2 billion kilometers. Voyager 2 is about 117 astronomical units from Earth, roughly 10.9 billion miles (17.5 billion kilometers). You can look at their current distances on this NASA website.

The Voyager spacecraft are expected to keep transmitting information until roughly 2025. In late 2017, NASA announced that it was able to reuse backup thrusters on the Voyager 1 spacecraft to improve its ability to point toward Earth. (The thrusters were last used for its Saturn flyby in 1980 and sat unused for 37 years, until NASA reactivated them.) This will allow it to send and receive information from controllers for another two to three years, NASA said at the time.

Even after shutting off, Voyager 1 and 2 will continue to drift out in interstellar space; they will both pass by other stars in about 40,000 years, according to NASA. Voyager 1 will come within 1.6 light-years of AC+79 3888, a star in the constellation Camelopardalis. Voyager 2 will fly by within 1.7 light-years of Ross 248; in 296,000 years, it will also come within 4.3 light-years from Sirius, which is the brightest star in Earth's sky.

Additional reporting by SPACE.com staff

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.