NASA's interstellar Voyager 1 spacecraft isn't doing so well — here's what we know

Since late 2023, engineers have been trying to get the Voyager spacecraft back online.

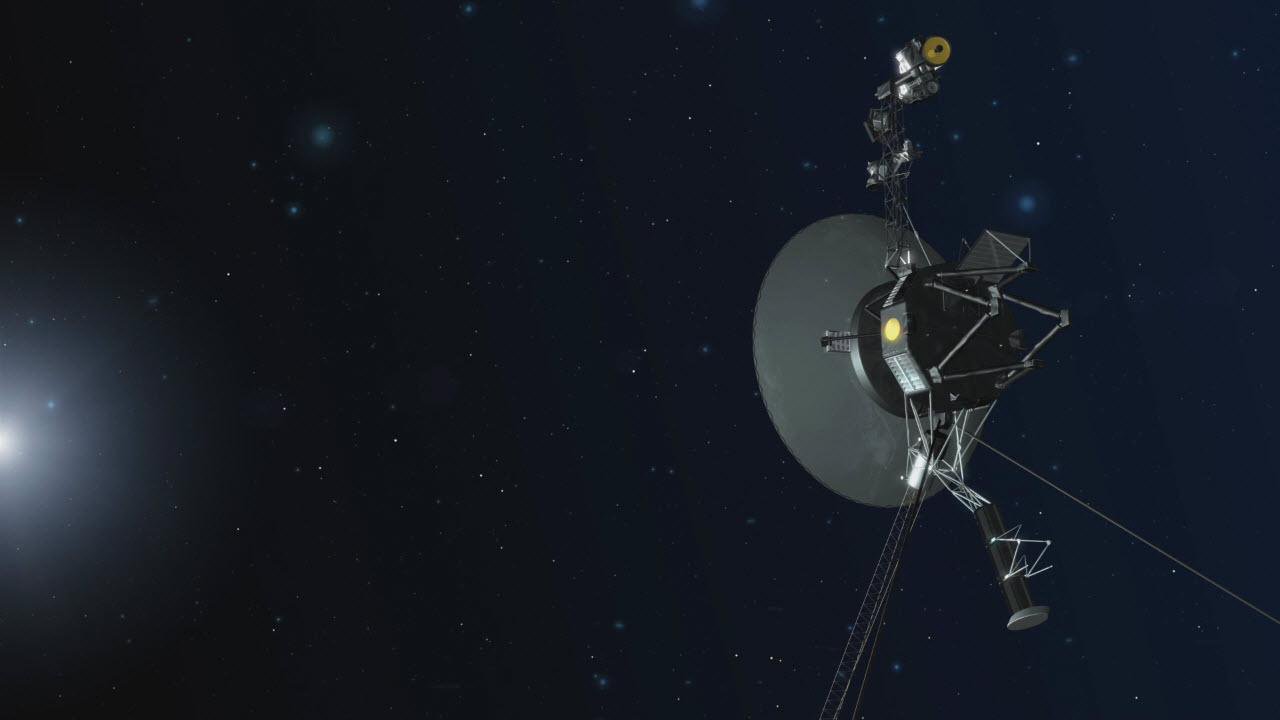

On Dec. 12, 2023, NASA shared some worrisome news about Voyager 1, the first probe to walk away from our solar system's gravitational party and enter the isolation of interstellar space. Surrounded by darkness, Voyager 1 seems to be glitching.

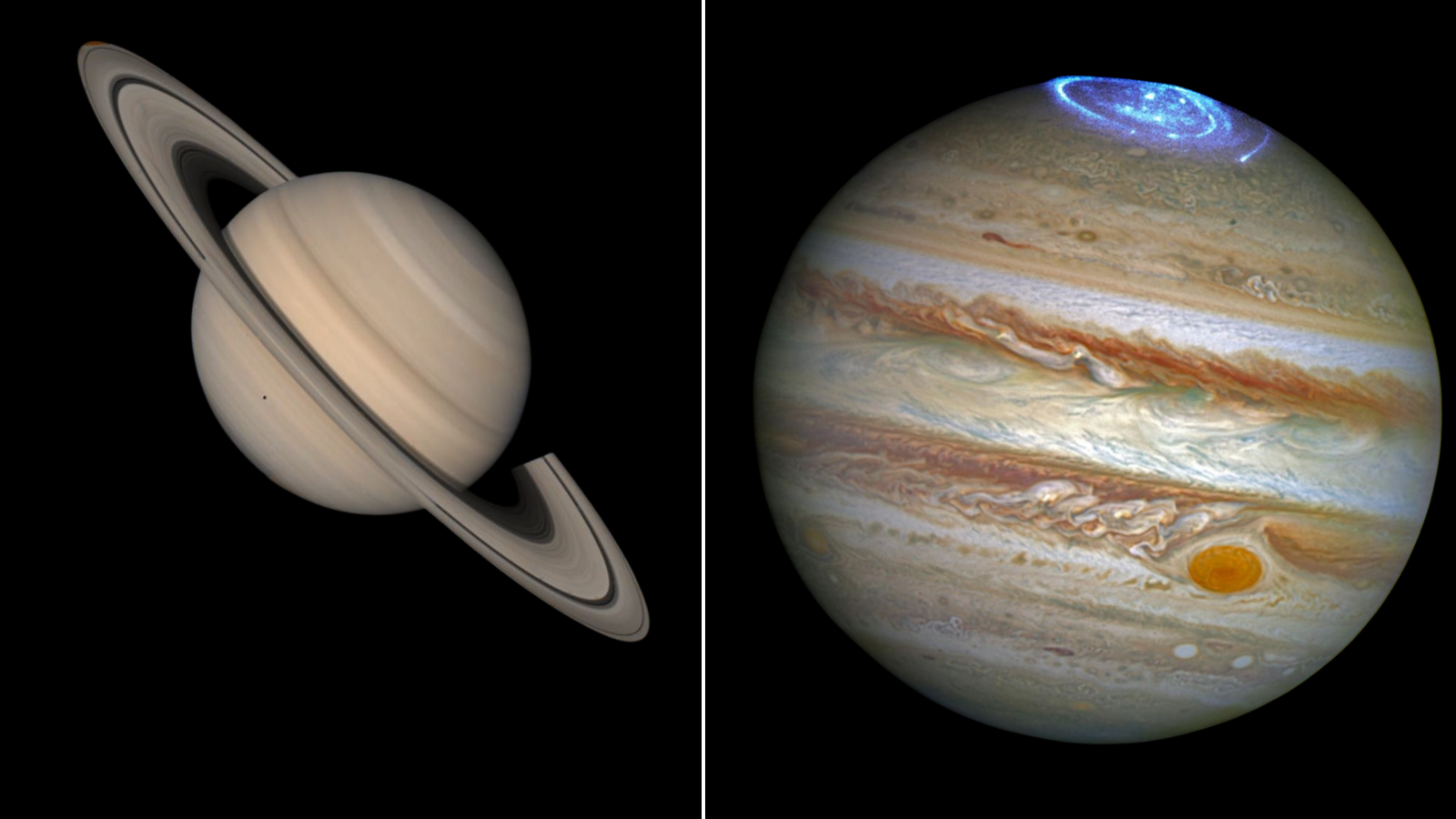

It has been out there for more than 45 years, having supplied us with a bounty of treasure like the discovery of two new moons of Jupiter, another incredible ring of Saturn and the warm feeling that comes from knowing pieces of our lives will drift across the cosmos even after we're gone. (See: The Golden Record.) But now, Voyager 1's fate seems to be uncertain.

As of Feb. 6, NASA said the team remains working on bringing the spacecraft back to proper health. "Engineers are still working to resolve a data issue on Voyager 1," NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory said in a post on X (formerly Twitter). "We can talk to the spacecraft, and it can hear us, but it's a slow process given the spacecraft's incredible distance from Earth."

Related: NASA's interstellar Voyager probes get software updates beamed from 12 billion miles away

So, on the bright side, even though Voyager 1 sits so utterly far away from us, ground control can actually communicate with it. In fact, last year, scientists beamed some software updates to the spacecraft as well as its counterpart, Voyager 2, from billions of miles away. Though on the dimmer side, due to that distance, a single back-and-forth communication between Voyager 1 and anyone on Earth takes a total of 45 hours. If NASA finds a solution, it won't be for some time.

The issue, engineers realized, has to do with one of Voyager 1's onboard computers known as the Flight Data System, or FDS. (The backup FDS stopped working in 1981.)

"The FDS is not communicating properly with one of the probe's subsystems, called the telemetry modulation unit (TMU)," NASA said in a blog post. "As a result, no science or engineering data is being sent back to Earth." This is of course despite the fact that ground control can indeed send information to Voyager 1, which, at the time of writing this article, sits about 162 AU's from our planet. One AU is equal to the distance between the Earth and the sun, or 149,597,870.7 kilometers (92,955,807.3 miles).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

From the beginning

Voyager 1's FDS dilemma was first noticed last year, after the probe's TMU stopped sending back clear data and started procuring a bunch of rubbish.

As NASA explains in the blog post, one of the FDS' core jobs is to collect information about the spacecraft itself, in terms of its health and general status. "It then combines that information into a single data 'package' to be sent back to Earth by the TMU," the post says. "The data is in the form of ones and zeros, or binary code."

However, the TMU seemed to be shuffling back a non-intelligible version of binary code recently. Or, as the team puts it, it seems like the system is "stuck." Yes, the engineers tried turning it off and on again.

That didn't work.

Then, in early February, Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told Ars Technica that the team might have pinpointed what's going on with the FDS at last. The theory is that the problem lies somewhere with the FDS' memory; there might be a computer bit that got corrupted. Unfortunately, though, because the FDS and TMU work together to relay information about the spacecraft's health, engineers are having a hard time figuring out where exactly the possible corruption may exist. The messenger is the one that needs a messenger.

They do know, however, that the spacecraft must be alive because they are receiving what's known as a "carrier tone." Carrier tone wavelengths don't carry information, but they are signals nonetheless, akin to a heartbeat. It's also worth considering that Voyager 1 has experienced problems before, such as in 2022 when the probe's "attitude articulation and control system" exhibited some blips that were ultimately patched up. Something similar happened to Voyager 2 during the summer of 2023, when Voyager 1's twin suffered some antenna complications before coming right back online again.

Still, Dodd says this situation has been the most serious since she began working on the historic Voyager mission.

Monisha Ravisetti is Space.com's Astronomy Editor. She covers black holes, star explosions, gravitational waves, exoplanet discoveries and other enigmas hidden across the fabric of space and time. Previously, she was a science writer at CNET, and before that, reported for The Academic Times. Prior to becoming a writer, she was an immunology researcher at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She graduated from New York University in 2018 with a B.A. in philosophy, physics and chemistry. She spends too much time playing online chess. Her favorite planet is Earth.