Why 'Space Madness' Fears Haunted NASA's Past

This story was edited to reflect the fact that the first astronauts were drawn from test pilots in all U.S. military services, rather than just the U.S. Air Force.

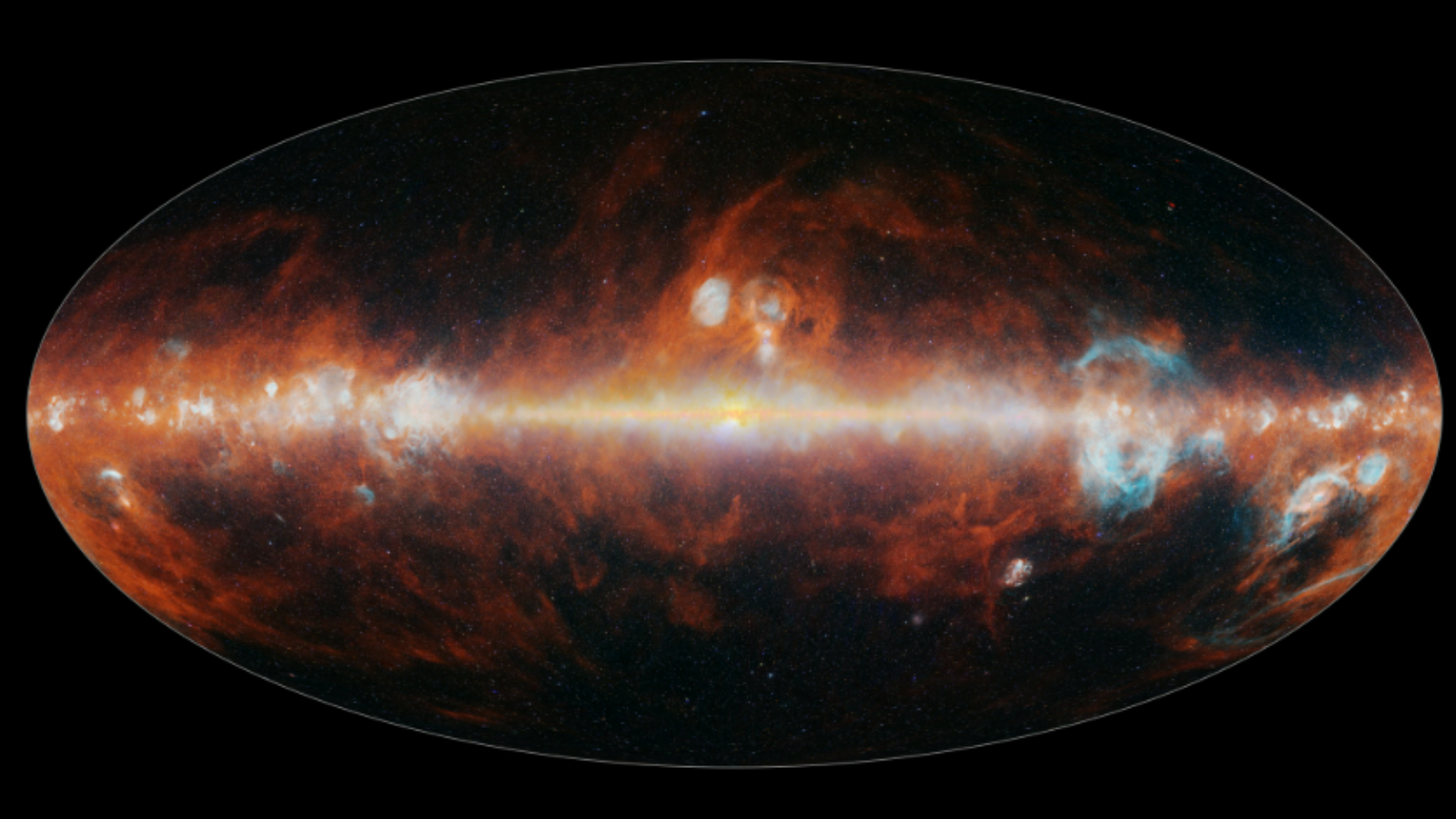

When astronauts first began flying in space, NASA worried about "space madness," a mental malady they thought might arise from humans experiencing microgravity and claustrophobic isolation inside of a cramped spacecraft high above the Earth. Such fears have since faded, but humanity continues to see spaceflight as having the power to transform people for either better or for worse.

Such early concerns of NASA psychiatrists led to careful screening of the first astronauts drawn from military test pilots. The astronauts proved highly professional and level-headed in even the most life-threatening scenarios — a reality that did not stop reporters and science fiction writers from imagining astronauts going crazy or becoming spiritually changed by spaceflight.

"People were making movies about astronauts suffering psychic stress long before any astronauts went into space," said Matthew Hersch, a historian of science and technology at the University of Pennsylvania. "They assumed leaving Earth and traveling into the heavens would be so traumatic that humans would have to respond in some way."

The sense of spaceflight's transformative power arose from both science fiction stories and from legitimate uncertainties about how traveling aboard a powerful rocket into the unknown might affect the human psyche, Hersch said. He also described how Americans projected their own hopes and fears of past decades onto the idea of spaceflight in a paper that appears in the March issue of the journal Endeavour.

Metamorphosis in space

U.S. astronauts and their Russian cosmonaut counterparts have mostly maintained their cool during long missions aboard space stations such as Skylab, Mir and the International Space Station. That stands in contrast to a rise in science fiction tales that are filled with space travelers going insane or experiencing life-changing moments.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"There are no examples of what we might consider freak-outs or psychotic breaks in any space missions," Hersch told InnovationNewsDaily. "There have been arguments, disagreements and occasional shouting."

Despite what writers like to imagine, astronauts displayed a businesslike attitude and stoicism in the face of danger that has proven popular with the American public. Neil Armstrong, the first human to walk on the moon, showed such calm when he was ejected from a jet-powered lunar landing simulator less than a second before it crashed to the ground — he surprised even his colleagues when he returned to work quietly at his desk barely an hour after the incident.

Pop culture and news reporting of the 1960s did their part in playing up the stoic image of astronauts. But writers and reporters of the 1970s wanted to see the more human side of astronauts — they imagined astronauts cracking under pressure or experiencing a spiritual transformation through spaceflight. But the astronauts ended up mostly disappointing them in both cases.

Have spacesuit, will travel

The opening of spaceflight to private citizens who fly as "space tourists" in the 21st century may again revive milder "space madness" concerns. "As we see space become more democratized with people who fly in space not being former test pilots, there are concerns about people flying in space without having had a lifetime of training for stressful situations," Hersch said.

Such concerns previously arose when NASA opened up its space shuttle program to more civilian scientists, engineers and teachers, but the civilian astronauts soon proved how well they could perform. Even the first few space tourists have mostly proven motivated and eager to undergo their own crash-course training.

Still, spacefaring nations already look beyond the imagined fears of space madness in planning for the real human challenges of new space missions. China has carefully screened its prospective astronauts (called taikonauts) for compatibility among possible space crews — an issue that was rarely considered during the early days of spaceflight. NASA has also paid more attention to its astronauts' psychological health on Earth in recent decades.

The wonder of it all

Space madness may mostly live on in science fiction stories rather than in reality. Yet the idea of spaceflight as a life-changing experience — something similar to a spiritual journey — is still strong in the minds of people shaping the future of space exploration. Such people range from the earliest rocket pioneers to the private spaceflight entrepreneurs of today.

"That kind of idea often motivates people who get into the spaceflight business," Hersch explained. "Virtually every spaceflight pioneer, including Werner von Braun, was steeped in the notion of spaceflight being good for its own sake, but justified it for military, business or technical capability reasons."

But will there ever be a time when spaceflight stops being seen as an automatic life-changing experience and starts becoming routine? Hersch thinks yes.

"It may take a few hundred years, but we'll eventually get there," Hersch said.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to SPACE.com. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.